In today’s public discourse, the use of terms like “animals” and “apes” to refer to members of historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups strikes a painful chord. In a related manner (though evoking less public outrage), terms like “monsters” and “sickos” are tossed about to refer to people with mental illnesses. These terms are particularly hurtful because they call up the distant memory of the eugenics movement, which gained prominence in the United States and elsewhere in the early 20th century, and eventually contributed to the atrocities of the Nazi Holocaust.

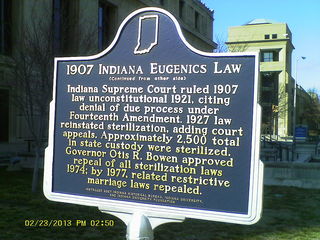

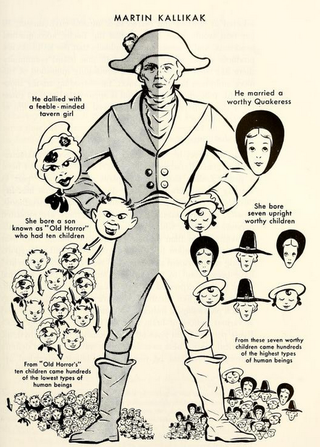

The eugenics movement, of course, did not create the belief that some groups of people are inferior to (or less human than) others, but it legitimized these views by lending them pseudo-scientific support. This, in turn, facilitated the development of policies that aimed to “improve” society. In the United States, policies derived from eugenic ideas included forced sterilization of the “feebleminded” and “insane” (enacted in 40 of 48 states) as well as an immigration law designed to keep out eastern and southern Europeans (not to mention all Asians), determined to be inferior to northern Europeans. In Nazi Germany, eugenic ideas were taken further to include large-scale “euthanasia” of people with mental illness and intellectual disability, and eventually the segregation and extermination of a number of ethnic groups (now known as the Holocaust).

Psychology played a special role in the legitimization of eugenic ideas in both the United States and elsewhere, largely because of the development of psychological testing approaches designed to measure intelligence. Findings from newly created tests were administered to groups presumed to be intellectually inferior, and provided quantitative confirmation of this view. For example, Carl Brigham, considered to be the “father of the SAT,” administered psychological tests to military recruits during World War I, and concluded that the tests “had proven beyond any scientific doubt that, like the American Negroes, the Italians and the Jews were genetically ineducable. It would be a waste of good money even to attempt to try to give these born morons and imbeciles a good Anglo-Saxon education.” Pseudo-scientific conclusions (based on the clearly invalid use of these culturally-biased tests) like these were used to support efforts to substantially limit immigration from members of these groups.

Psychology and psychiatry also contributed to the actions of the eugenic movement with regard to mental illness. In the early 20th century, German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin revolutionized psychiatry by drawing a distinction between the two main forms of what had been until then simply called insanity- manic-depressive psychosis (now called bipolar I disorder) and dementia praecox (now called schizophrenia). Although he died before the beginning of the Third Reich, Kraepelin’s assertion that dementia praecox had an inevitably hopeless and deteriorating course provided cover for the Nazi regime’s decision to enact their “euthanasia” program.

Though Kraepelin’s views about the course of schizophrenia were found to be unsupported over 30 years ago, many in the general public continue to believe that people diagnosed with schizophrenia cannot recover. In fact, research finds that exposure to information about the biological and genetic contributions to disorders such as schizophrenia is associated with increased support for these negative stereotypes. This is likely the case because many members of the general public struggle to understand that human characteristics can be both “genetically-influenced” and “changeable”— a nuance that runs counter to the eugenics-derived view that people are born, not made.

Today, eugenic ideas live on in coded statements like those quoted above, that reduce members of entire groups to less-than-human statuses. Though we might now be inclined to see these statements as nothing more than private opinions, in the early 20th century, these ideas had a very real impact on social policy that caused a tremendous amount of damage in the world. We should remain vigilant regarding the possibility of their re-emergence.