Coronavirus Disease 2019

How to Tackle COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy

Motivational interviewing is an evidence-based communication style.

Posted January 26, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

What people really need is a good listening to. —Mary Lou Casey

If you were on a Zoom call with ten American family members or friends over the holiday season, then statistically, it is likely the case that about four of them would say that they would not get a COVID-19 vaccine. And based on the same survey from the Pew Research Center, only about two of the four would admit to the possibility of changing their minds, while the other two are pretty certain that they would not.

Undoubtedly, this is alarming in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially where we have witnessed the human triumphant development of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines.

But it is also unsurprising. The world of psychology has taught us important lessons. We know, for instance, that if you tell someone what to do, then they’ll be tempted to do the opposite—a phenomenon known as psychological reactance. We also know that people don’t make vaccine decisions purely based on rationality and statistics, but rather do so by coloring information with their emotions, perceptions, and beliefs.

The beliefs that people hold towards vaccines lie on a spectrum of skepticism. Some people espouse extreme views that derive from the anti-vaccine movement, which describes a campaign aimed at discrediting vaccines by spreading disinformation and conspiracies. It is difficult to change the minds of people who are married to anti-vaccine ideology, as motivated reasoning processes can sustain the strength of such beliefs—in other words, if your self-identity and worldview are closely wrapped up with particular beliefs that you hold, then you will experience challenges to those beliefs as threatening, which may motivate you to cling to them harder.

Most people, however, are rightly critical and curious about vaccines, which we might describe as vaccine-hesitant. These are the folks who are open to changing their mind when they encounter trusted information.

But vaccine hesitancy is no joke. The World Health Organization has named it a threat to global health. Much has been written about how to best address it from multiple public health approaches.

At the level of the individual, it has been suggested that motivational interviewing (MI) may be a powerful tool to address vaccine hesitancy. MI is an evidence-based communication style that has been heavily researched and used, especially in the realm of addiction and mental health. It is used to help motivate people to make changes to their behavior. Evidence for the effectiveness of MI on vaccine hesitancy is strong. Here is what MI looks like from a practical perspective so that you might consider using it in conversation.

Motivational Interviewing (MI)

While proficiency in MI requires training (especially for clinicians that plan to use it ethically and competently in the context of addiction and mental health treatment) and is not something that one can learn quickly, its general empathic, non-judgmental approach to conversation is better than the alternative approach of patronizing confrontation.

It is most helpful to understand MI in two ways: its spirit and its techniques.

The Spirit of MI

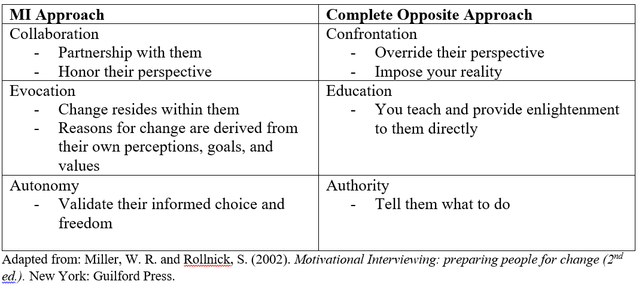

While “spirit” might sound like an odd term, it is meant to capture your attitude when engaging in conversation. The spirit of MI is to respect the other person’s perspective instead of imposing your reality on to them (Collaboration); it’s to help the other person make changes by drawing on their own reasons for doing so (Evocation); and it’s to validate the other person’s independence and personal control over their life (Autonomy).

The Techniques of MI

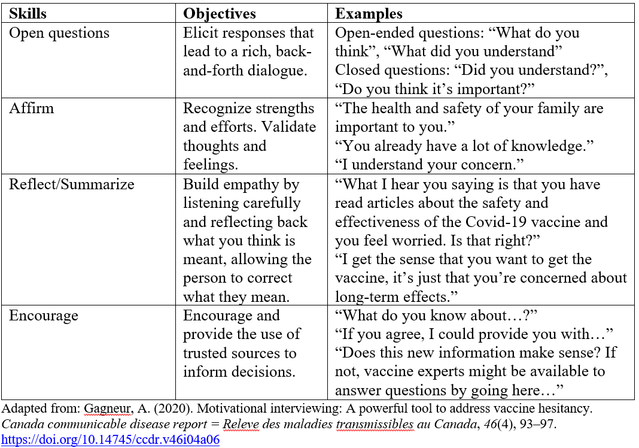

The techniques of MI are the mechanics—how to actually do it. There are many techniques to MI but as a basic starting point, it’s helpful to remember its core conversation skills, captured by the mnemonic acronym OARS: ask Open Questions, Affirm, Reflect, and Summarize. In a nutshell, this means that your goal is to sit with a person and listen reflectively, validate their concerns and questions, and empathize with their feelings.

Finally, you can encourage them to seek out trusted sources to answer their questions, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and COVID-19 Resources Canada. You can encourage the use of critical thinking that is balanced with trust in scientific expertise and consensus rather than uncorroborated horror stories that they might read on social media platforms. You can also encourage the use of accurate information to weigh the pros and cons of getting the vaccine versus remaining unvaccinated.

At the end of the day, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is a complicated problem that requires intervention at many levels: from public policy, to social media, to individual conversations. MI is but one of these interventions at the individual level that could make a difference anywhere from a family physician’s office to a Zoom call with a friend. But don’t take my word for it—think about it, have a look at the evidence, and then decide for yourself if it’s worthwhile.