Suicide

Why Do Some of Us Look Forward to the End of the World?

A Personal Perspective: The dangers of the Apocalypse mindset.

Posted October 21, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- A Peak Oil theorist committed suicide after new oil reserves were discovered.

- A religious sect called the Millerites disbanded after the Apocalypse didn't occur as prophesied.

- For some people, an end-of-the-world mentality can give life more meaning—but it can also threaten their health and life satisfaction.

There was a man I used to follow on the internet. Some called him a madman and a conspiracy theorist because he was convinced that civilization was about to collapse. He’d built up detailed data on the theory that we know as Peak Oil; he’d mapped out the stages of the coming cataclysm. He passionately believed that his role in life was to warn us all.

His suicide in 2014 posed a huge psychological question for me.

It’s important to understand the details of what he believed.

Peak Oil Theory

Oil is a finite resource, and once the peak of oil production is reached, it will go into rapid decline across the globe. As a result, the manufacture of plastics, medicines, and fertilizers (and a further 6,000 items from detergents to lifejackets), all of which are dependent upon crude oil, will go into irreversible collapse. Oil-dependent power generation will cease. Civilization will rapidly head back towards the “carrying capacity of the planet” that existed prior to the industrial revolution.

One emotive point the Peak Oil theorist made was that for millennia before fossil fuels, the population of the world had remained constant at around 1 billion. We are currently at a world population of 7.98 billion. When Peak Oil hits, and we are forced to deindustrialize, he claimed, 6.98 billion people would be “surplus to requirement.” They’d be left to starve and freeze in the “die-off.”

This man’s Armageddon was due to begin as soon as 2040 when oil began to run out. He appeared on one video, weeping, trying to warn us all.

Back in 2013, I’d found his emotion, fear, and even his warning compelling.

Then in 2014, he committed suicide.

What led to his suicide was not that “the end was nigh” or that “no one would listen,” it was, paradoxically, that around 2014, vast new oil reserves were found around the globe, and new ways of accessing oil and gas became credible (fracking, oil shale). In 2014, scientists pushed back the projected peak in oil production by a hundred years till 2100.

His Apocalypse was postponed to well beyond his own lifetime, and in reaction, he put his dog where a neighbor would find it, and he shot himself in the head.

It’s a mystery. Surely, you would think he would have been relieved that humankind had been given a reprieve.

The answer to this riddle may come from another historical apocalypse that was postponed.

The Great Disappointment

In the 19th century, the head of the Christian Millerite movement, the Baptist preacher William Miller, prophesized that the Second Coming of Christ would occur in 1844, bringing on the Last Judgement and cleansing the world of sin, as millions were cast into hell. Miller had calculated the exact date meticulously, using numerology, and the Day of Judgment, he said, would take place on April 18, 1844.

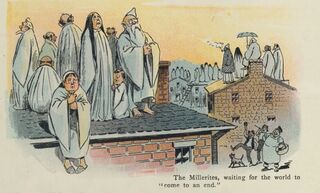

Many of his followers (estimates vary between 50,000 and 500,000) sold their homes and gave away their jewelry and livestock in readiness. When this “last day” came and went, he told his followers that he’d miscalculated by seven months and that the Apocalypse would now be on October 22, 1844.

Again, on this day, his followers climbed hills and rooftops to await ascension. After that day passed without event, one of Miller’s followers wrote.

“I waited all Tuesday [October 22] and dear Jesus did not come; I waited all the forenoon of Wednesday, and was well in body as I ever was, but after 12 o'clock I began to feel faint, and before dark, I needed someone to help me up to my chamber, as my natural strength was leaving me very fast, and I lay prostrate for 2 days without any pain—sick with disappointment.”

Millerite, Hiram Edson, recorded, "Our fondest hopes and expectations were blasted, and such a spirit of weeping came over us as I never experienced before... We wept, and wept, till the day dawn.”

Chaos erupted. One Millerite church in Ithaca, New York, was burned to the ground, a group of Millerites was tarred and feathered in Toronto for having caused such panic, and another Millerite group in Illinois was attacked with clubs and knives. The Millerites themselves were left bewildered and disillusioned.

Their sect disbanded in dismay. The newspapers of the day reported detailed cases of insanity and suicide from among the disappointed Millerites who’d been unable to return to normal life.

A 16-year-old Millerite girl, Ellen White, wrote, “It was hard to take up the vexing cares of life that we thought had been laid down forever. It was a bitter disappointment that fell upon the little flock whose faith had been so strong and whose hope had been so high.’

Apocalypse Dependence

It poses a curious question about human psychology—why would some people be so absorbed by the idea of the Apocalypse that when it fails to occur, they sink into despair?

For the Millerites, there was, of course, the promise of Heaven and the frenzy of religious faith, but our Peak Oil theorist seemed to be much more concerned with the human tragedy of 6.9 billion deaths than he was with his own salvation.

To be so disappointed that the world is not ending that you kill yourself.

What I think the Peak Oil theorist and the Millerites share is the idea that a single narrative that explains all of existence can give a person’s life a great sense of meaning, direction, and hope. Even if that narrative concludes in certain death for the believer, their life is given immense value. The believer is one of “the chosen,” “the elect.” They possess “the only truth,” and this sets them above the masses of non-believers, the sheep, the blind.

This is illustrated by the fact that so many Millerites suffered from what must have been cognitive dissonance after their great disappointment and, unable to admit that they’d been wrong, they went on to invest in new apocalypse date predictions—and so the Advent Christian Church and the Seven Day Adventist sects were born.

In this sense, we might talk of a psychological dependence on the apocalypse narrative. A paradox, but yet, in a world in which there is so much uncertainty and conflict, a belief in a fated and meaningful “end to all life” might seem a more consoling option than a life lived without any kind of guiding narrative at all—a life of meaningless fragments that is itself a “great disappointment.”

Why do I raise this issue now?

There is so much fear of Apocalypse in our time, be it nuclear war or climate change, or a new pandemic, and these anxieties seem legitimate. But we might want to be careful about how much we come to depend on such narratives to give our lives meaning.