Sexual Abuse

There's No One "Right" Reaction to Childhood Sexual Abuse

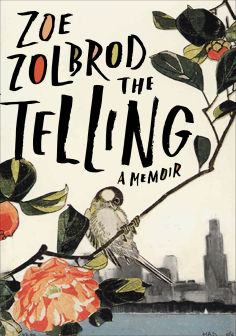

Zoe Zolbrod's new memoir explores the grey areas of trauma and recovery.

Posted July 24, 2016

As a kid, Zoe Zolbrod kept a secret: Between the ages of four and five, she was routinely molested by her teenaged cousin who lived with the family. When she finally decided to talk about it, she wasn’t sure what to expect, what to say, or who to tell.

Was she reacting to her sexual abuse the wrong way? Was she telling it the wrong way?

After becoming a mother herself, Zoe learned that the man who abused her was in jail for doing the same thing to another little girl. This time, she decided to tell the whole world about her experience--and its surprising aftermath--in a unique and transfixing new memoir, The Telling.

Ariel Gore: The Telling weaves three experiences of being female: Childhood sexual abuse, unfurling adolescent sexuality, and motherhood.

The narrative a lot of us have heard about childhood sexual abuse is that it’s always life-destroyingly traumatic. Your story suggests that each of us processes that trauma in a different way. Can you talk about the sense of having a “right” or “wrong” reaction to abuse?

Zoe Zolbrod: Even as we as a society turn a blind eye to sexual abuse in so many way, the dominant narrative is that it’s the most disgusting and horrific of all crimes. How many times have I heard that child molesters get pummeled in prisons, that even murderers and drug dealers see them as the lowest as the low? So it’s easy to surmise that any normal person would immediately experience this kind of abuse as abhorrent and repellent, as the worst thing that ever happened to them. So bad that they might have to block it out entirely just to go on functioning. Being at all muddled or confused about the abuse appears deviant and suspicious in this light, or at least the mark of someone who's in denial.

But according to research—specifically that of Susan A. Clancy, documented in her book The Trauma Myth—many children don’t experience abuse as traumatic at the time it’s occurring. When they get older and realize the nature of what was done to them, that’s when they freak out, and part of what can cause depression and guilt is that their initial response didn't match what they think it should have (which fits with what I've heard anecdotally). When I've read online articles about this, or reviews of Clancy's book, they're often followed with lots of irate comments. I guess people fear that if we acknowledge any slightly gray area, we're leaving the door open for people to say that child sexual abuse isn't always that bad—but I haven't come across anyone outside of overt sex offenders groups who implies that.

Ariel: Your stories about adolescent sexuality are often so innocent and playful. Why do you think teen sex gets such a bad rap in our culture?

ZZ: Well, speaking as a parent, the consequences of sex can be huge, and the adolescent brain is not wired to consider consequences carefully, so I get that there’s reason for concern, some sense in adults reminding teenagers to slow down. We want to protect young people we still see as children.

But there seems to be more to it than that. I chalk it up to general puritanism and a fear of libidinal energy and maybe even some unconscious jealousy—both of our kids, for the pleasures of youth that are elusive in middle age, and over our kids, who will be pulled farther from us. We know about the bad stuff that can come from sex—the risks, the way girls, in particular (although not exclusively), can be vulnerable to bad actors—but we also know that the overwhelming power of good sex, of lust and love, will sweep our children away where we can’t follow.

Ariel: Have you had any feedback that your story downplays the effects of sexual abuse? If so, what do you make of that feedback?

ZZ: Yes, indirectly and through Twitter, I’ve heard from people who think I downplay the effects and use the topic as a cheap self-empowerment device. Having spent so much time lurking around discussions of sexual abuse, I expected this, and it was almost satisfying to see it. At least someone is reading the book and cares enough to take issue.

"I wrestled for years with the feeling that I’ve been doing my sexual abuse wrong, and my more-or-less sanguine reaction to the criticism tells me that I’ve come out the other end; I’m comfortable owning my particular experience."

It helps that in the process of publishing the book I’ve heard from so many people who relate to it.

Ariel: Can you talk more about the responses you've gotten from people who relate?

ZZ: What’s most striking to me—after years of worrying about how I’d handle having this book out in the world, and fearing the ick and the stigma I felt to be associated with this topic—is how comfortable and open so many people are talking about this. I’ve been part of some great public conversations where people are speaking their minds, referencing their own experiences, acknowledging nuance. On the one hand, I’m sad to see the statistics come to life, to learn first-hand how many people have been sexually abused as children. But on the other hand, it’s really, really interesting and comforting to be able to talk to people matter-of-factly.

Ariel: Being a parent provides whole new mind-bends around sexuality, childhood abuse, gender, and the body. Did you ever consider writing The Telling without the motherhood perspective? What would have been lost?

ZZ: Three months after I became a mother I learned the man who abused me was in jail for doing the same thing to another little girl, and the shock of that news in my postpartum state was what caused me to revisit my history and to delve into the topic of child sexual abuse and pedophilia in general. The impulse was entirely wrapped up in feeling a new responsibility for children, and also in recognizing how complicated the child-parent bond can be, how hard it is to be a parent. The conversation between the generations was what made it an interesting story to me and what convinced me it was worth sharing. Without those layers, I don’t think I could have achieved the scope I was shooting for.