Attachment

Can Your Attachment Style Change?

Learn to identify your style as well as navigate its fluctuations.

Posted April 20, 2022 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Attachment theory identifies three primary styles: secure, insecure ambivalent, and insecure avoidant.

- Attachment styles can fluctuate over a lifetime and even from relationship/situation to relationship/situation.

Attachment theory has been prominent for decades now. It’s popped up in pop culture, and continues to be a fulcrum of both parenting and partnering with support from a range of experts, including Dan Siegel, Tina Payne Bryson, Amir Levine, Stan Tatkin, and Susan Johnson.

Attachment Style Basics

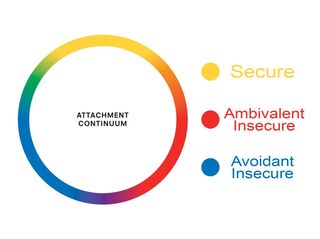

Let's start with a quick primer. There are four attachment styles: secure, insecure ambivalent, insecure avoidant, and disorganized, although most attention focuses on the first three. They are typically pictured on a continuum, with secure attachment at the center.

Attachment theory draws heavily on the work of John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. They postulated that when humans are offered a strong and dependable bonding experience with their earliest primary caregiver(s), they develop a general sense of safety and security. With this secure base, it’s easier to relax into life, relate well to your partner and others, and raise children who are also secure. This is called secure attachment.

Insecure attachment, either avoidant or ambivalent, can result if a caregiver has that style themselves, is depressed, is dealing with their own unresolved trauma, or is struggling with other stressors that cause them to be less available to their baby or child. In broad strokes, those with ambivalent attachment had inconsistent bonding with their caregiver and find as adults that it’s easier to care for others than for themselves. They have deep feelings of abandonment and a hard time asking for their needs to be met. Avoidant attachment can result from childhood with a neglectful caregiver and is characterized by extreme self-reliance, a preference for being alone, and a hard time trusting that others will care for them.

There is nothing inherently wrong with any attachment style. But identifying and understanding yours can give you a better understanding of yourself and your relationships with your partner, children, friends, and coworkers. (Books by the experts mentioned above can help.) You can use this understanding to predict how you (and others) will handle transitions, such as switching careers or becoming a parent. It can also help you be empathetic to yourself when certain issues seem to plague you—such as chronic difficulty asking for help or a serious avoidance of conflict.

Change Your Style

Can your attachment style change? The answer is yes.

Even though we typically identify with one style, we’re too complex as people to be stuck with one for life: We’re continually changing, growing, and adapting to our relationships and environment, which also influences our style. Research by Chopik and others has identified trends in attachment over the lifespan. For example, anxious attachment tends to be highest during the teenage years and young adulthood. Avoidant attachment tends to decline throughout life. And an increase in secure attachment is associated with being in a happy romantic relationship.

More recently, Hudson and colleagues demonstrated that people can intentionally change their attachment style to become less anxious or less avoidant by setting a goal to do so and essentially “faking it till they make it," though whether that change is lasting remains an open question.

Your style can also fluctuate under different circumstances, even during a single period of your life. For example, you might operate from a secure style in one relationship or setting (e.g., with a partner), while operating from an insecure style in another (e.g., with your boss). Stress can play a big role, too. Life’s ups and downs, the ability to sleep, how well you take care of your basic needs—all feed into your attachment style. I’d be willing to wager that the pandemic caused many to make a major shift on the attachment continuum.

The Continuum

Because of these variable dynamics, I like to visualize the attachment styles on a circular rather than linear continuum. I think seeing them in technicolor (as below) allows for an openness to whatever style you are operating from in any given situation, without judgment or labels of pathology.

In my continuum, yellow is for secure, red is for ambivalent, and blue is for avoidant. Notice that the shades of green, purple, and orange show how you can move through life or from situation to situation. You can be orange when you feel secure but are simultaneously extra vigilant about your safety. When you feel secure but also a bit clingy, you may hover in the purple space. Fear of conflict, alongside some confidence that conflict can be tolerated and eventually worked out, is represented by green.

As you gain a greater feel for your attachment styles...

- Notice their subtleties.

- Notice their range.

- Notice why they change when they do.

- Notice what you can change through your volition and what you can’t.

- Notice how your partner or friends can support you in this process.

- Notice the effects on your kids.

References

Ainsworth, Mary D. S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bowlby, John. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books.

Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., & Grimm, K. J. (2019). Longitudinal changes in attachment orientation over a 59-year period. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(4), 598–611. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000167

Hudson, Nathan W., Chopik, William J., & Briley, Daniel A. (2020). Volitional change in adult attachment: Can people who want to become less anxious and avoidant move closer towards realizing those goals? European Journal of Personality, 34, 93–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2226