Suicide

Murder, Guns, and Mental Illness: What the Statistics Show

Statistics can help trace the causal structure of gun violence in the U.S.

Posted May 27, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Prevalence of guns appears to be strongly related to gun violence across the 50 states.

- Mental health does not appear to be statistically related to gun violence across the 50 states.

- Mass shootings can be (and have been in the past) reduced by restricting assault rifles.

- Suicide is also a serious problem that is strongly related to gun prevalence.

Part of how we stay civil with one another is that we feel connected to one another. When we feel that human connection, when we sense that “the other” is actually very similar to ourselves, it is easy to feel compassion and a sense of shared destiny.

(Note that whether we feel it or not, we humans do all have a shared destiny. And if we don’t feel it, then that shared destiny will not be a good one.)

Years ago, I lived in upstate New York. As a white male, I sometimes blended in pretty well, but I did have long hair and a full beard. This made me stand out in certain parts of that northeast culture. When I would greet a stranger on the sidewalk with a nod and a smile, sometimes they would meet my gaze but neither acknowledge nor reciprocate my friendly greeting. They would just stare at me with a blank expression on their face. I think they felt, because of my long hair and full beard, that I was “the other” and they felt no similarity with me and no compassion for me, no connectedness with me. They saw me as belonging to some other tribe.

This is the kind of subtle microaggression that my ethnic minority friends tell me they experience every day in the U.S. Shortly after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, as the TSA increased its security measures at airports, one of my professional colleagues said to me, “you must really get scrutinized there.” At first, I had no idea why he had singled me out. I naively asked, “Why me?” He said, “because of your long hair and beard,” as he waved a hand around at my appearance. It reminded me that even people who accepted me still categorized me as “generally perceived as the other”—even if I frequently forgot that fact.

Mistreatment of “the other” is behavior that can also be seen outside the human species. For example, chimpanzees are a species of Great Ape who are extremely tribal. They will kill and eat fellow chimpanzees who belong to another community. They perceive outsider chimps as “the other.” By contrast, bonobos are a species of Great Ape who are accepting of fellow bonobos from other communities. They treat stranger bonobos the way the Good Samaritan treated an injured Jew in the Bible—they welcome them and help them. Humans are a species of Great Ape who are, perhaps, somewhere in between those two extremes.

The only way a human can shoot another human whom they do not know is to conceive of them as “the other”—an enemy to whom they are not connected. (The U.S. military spent decades researching how to train their soldiers to treat fellow humans as “the other” and shoot them—so they would stop missing their human targets on purpose.)

With over 200 mass shootings in the U.S. this year—and it’s not even June yet—it behooves one to ask the following question: Why are Americans so ready to see fellow Americans as “the other” and shoot them? Other wealthy countries don’t have this problem.

One obvious possibility is the overwhelming prevalence of gun ownership throughout the U.S. Although it varies substantially across the 50 states, about a third of all American adults own guns. In fact, the U.S. has the most guns per capita in the world, about twice as many as second and third place (Yemen and Switzerland, respectively). With 50 states that have different levels of gun ownership and different rates of gun deaths, the real-life experiment to test for this relationship is already being conducted.

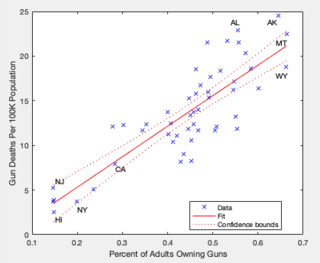

If you compare the percentage of adults who own guns across all 50 states with the per capita gun deaths across those 50 states, the correlation is remarkable (Figure 1). States where more people own guns are the states that have high rates of gun deaths.

The correlation in Figure 1 is robustly statistically significant and shows that 70 percent of the variance in gun deaths across the states is accounted for by the prevalence of guns in those states. Thus, it looks like the prevalence of gun ownership may be playing a role in the prevalence of gun deaths. That said, correlation does not equal causation. It is possible, as some have suggested, that mental illness is what actually causes gun deaths. So, let’s look at mental illness rates per capita by state.

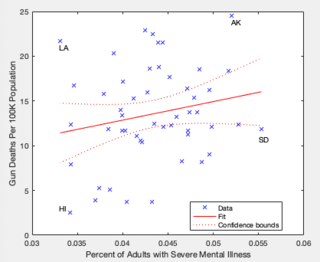

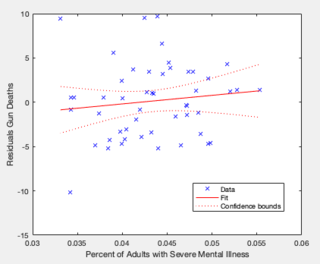

The correlation in Figure 2 does not even approach statistical significance. The prevalence of mental illness in a state does not appear to be playing a role in the prevalence of guns deaths in that state.

You might ask, “What about gun suicides? Does that taint your statistics?” Good question.

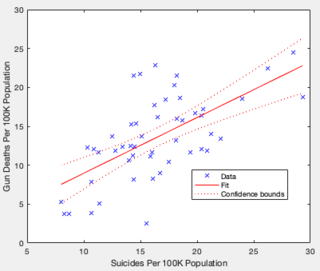

A majority of gun deaths in the U.S. are, in fact, suicides, not homicides. Some folks might prefer to exclude those data from this analysis – although it is not obvious that we would want to do that. Reducing suicides might be a good thing too.

If we look at the relationship between suicide rates (with any method) and gun deaths (Figure 3), it too shows a statistically significant correlation – though not as robust as Figure 1. It shows that 40 percent of the variance in gun deaths across the states is accounted for by the suicide rate in those states. This is, of course, because many of those suicides are carried out with guns. We can now subtract that suicide factor out of our analysis by looking at the residuals from this data fit. The residuals are the values by which each data point deviates from the predicted red line. Some residuals are higher than the predicted red line and thus are positive values. Some residuals are lower than the predicted red line and thus are negative values. These residuals describe the state-by-state variance in gun deaths that is not accounted for by suicide. Can those residuals be accounted for by gun ownership rates?

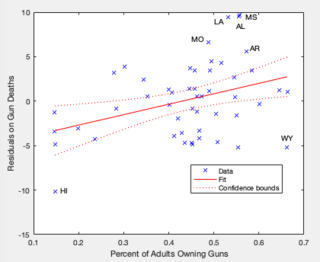

Yes. When suicides are subtracted out of the equation, gun deaths are still reliably predicted by gun ownership rates with robust statistical significance (p<.01). See Figure 4. What’s more, they are still not predicted by mental illness rates (p>.4). See Figure 5.

To further complicate matters, mental illness rates from state to state do not predict suicide rates. But gun ownership (particularly pistols) very much does. Thus, rather than mental illness causing suicidal thoughts and then those thoughts causing suicide by gun, it may instead be that suicidal thoughts come and go relatively unpredictably with almost anyone, and simply having a gun nearby during one of those moments can lead to suicide by gun (the most effective method of suicide). That’s what these statistical results are consistent with.

With a knife or a baseball bat, one has to get up close and personal to kill someone. Getting that close exposes you to that person’s humanity. It also gives them a good chance to defend themselves. With a gun, especially an assault rifle that doesn’t need to be reloaded frequently, witnessing someone’s fellow humanity (or reacting to their self-defense) is no longer an issue. Perceiving them as “the other” will not get interrupted by any pesky sense of connectedness with a fellow human being. Just like suicide by gun is the most effective method because it generally doesn’t give you a chance for any second thoughts, so it is with homicide by gun.

Hunting rifles and shotguns are useful for killing nonhuman animals under appropriate circumstances. Shotguns and pistols are useful for home defense. When it comes to mass shootings, they are not the problem. Those are the kinds of guns that most other countries have in abundance, and those countries are not awash in gun deaths. How can the U.S. stem its rising tide of gun homicides? Embracing our connectedness with one another can only go so far. Based on the statistical analyses above, our best chance at reducing gun deaths in the U.S. may simply be reducing the prevalence of guns that are made specifically for killing lots of fellow humans quickly.