Coronavirus Disease 2019

Why You Should Trust the Scientists on COVID-19

Trust the medical scientists on coronavirus, not the fringe theorists.

Posted April 30, 2020

It feels good to know something that other people don’t know, doesn’t it? In school, the students who know the answers to the teacher’s questions get positive feedback from the teacher. The students who don’t know the answers feel left out. This may be part of why people enjoy exploring fringe theories and conspiracy theories. When you embrace a fringe theory, you feel like you know something that other people don’t know.

On various topics, many Americans have been dismissing scientific experts and trying out fringe theories. Some of these are relatively harmless. For example, dismissing science by being a flat-earther won’t kill you. Distrusting government by being a moon-landing denier won’t kill you. Even discarding the evidence for climate change probably won’t kill you (though it might kill your children). But dissembling the truth about COVID-19 can genuinely kill you!

False rumors and disinformation can spread in a fashion similar to the spread of a biological virus. They are almost like a mental virus (Jin et al., 2013; Spivey, 2017; Vosoughi, Roy, and Aral, 2018; see also Holbrook and Hahn-Holbrook, 2020). Indeed, many American citizens have been living in an unprecedented bubble of false information and “alternative facts,” seemingly unharmed by it, for over three years now. So, when the actual medical facts about coronavirus get muddled by those in government, many Americans have a tendency to buy into that new false information just as easily as they did before. “Let’s live in a world of alternative facts regarding coronavirus, too. This alternative world we’ve fashioned for ourselves hasn’t harmed us yet, right?”

But it is harming people. There are thousands of Americans who are dead now who didn’t have to die. Many took the advice of certain politicians to not stay-at-home and not wear a mask in public, instead of taking the advice of medical professionals to safely shelter-in-place during this coronavirus pandemic. The family members of those victims have lost their loved ones, not because it was inevitable, but because some politician assured them that coronavirus was “no worse than the common flu, believe me.”

When your water heater breaks down, you don’t seek advice from your veterinarian to fix it. When you have a hernia or a broken nose, you don’t call your state senator to fix it. You want to consult an expert in that field, right? So, when a virus pandemic breaks out, why would you seek the advice of a politician or an economist? We need to seek advice from trained medical scientists. (In fact, medical practitioners who don't have training in scientific study design can get it wrong too.)

A few weeks ago, the U.S. president was boasting about his knowledge of medical science. He bragged, “Every one of these doctors said, ‘How do you know so much about this?’ Maybe I have a natural ability.” But then, last week, he suggested that people try injecting disinfectant into their bodies to fight the coronavirus. Over the weekend, a Kansas man tried it.

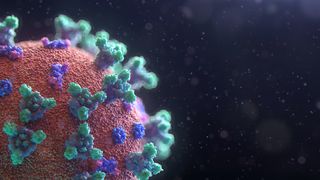

Let’s get something straight. Your body’s cells and a virus particle are very different, but they have some biochemical mechanisms in common. This coronavirus has a fatty membrane surrounding its particles, much like human cells have, and it injects its RNA into a biological cell in order to commandeer that cell’s genetic instructions. Since human cells and these virus particles have similar fatty membranes, many of the remedies that rupture a virus particle will also harm human cells as well. In fact, the majority of cells in and on your body are actually viruses, bacteria, and fungi—not human cells (Dietert, 2016; Spivey, 2020; Tauber, 2017). So, it should come as no surprise that your body would react poorly to the same things that will kill the coronavirus. As immunologist Rodney Dietert quips, “We have met the microbes, and they are us.”

An expert in medical science knows that the biochemistry of a human cell and of a virus particle have some important things in common. A politician who is dabbling in medical science doesn’t know this. Psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger have studied the effects of dabbling in a topic. The Dunning-Kruger Effect shows how partial training in a subject can actually induce a problematic level of overconfidence in one’s own skills. If you just-barely know what you’re talking about, then you probably realize it while it’s happening, and you may offer some caveats like, “at least, that’s a possibility.” However, if you really, really don’t know what you’re talking about, then you don’t even realize it while it’s happening. You just think what you’re saying is smart.

In 1709, Alexander Pope wrote, “A little learning is a dangerous thing.” What he meant was that someone with no learning on a topic is usually well aware that their knowledge is minimal on that topic. Someone with a substantial amount of learning on a topic has often been made aware that there is still very much they have not yet learned about it, so they use some caveats in their wording. However, someone with just a little learning on that topic can sometimes falsely conclude that they know all that needs to be known about it—especially if they have a narcissistic personality disorder.

As you become an expert on a topic, there are two broad categories of things you learn: you learn a great deal that’s true about that topic, and you also learn that there is a great deal not yet fully understood about that topic—at least not by you so far. That second type of learning is probably the most important because it instills some humility and open-mindedness in one’s attempts to find solutions to problems in that topic. Unfortunately, that second type of learning often doesn’t happen until you’ve had years of training and experience with that topic.

The medical experts, with decades of experience in epidemiology, have been accurately advising us to shelter-in-place when possible, maintain social distancing, wear masks in public, disinfect packages that arrive at the house, and wash our hands frequently. They have also been humble and open-minded enough to acknowledge that this novel coronavirus is surprising us with new symptoms and different strains. If you want safe advice on what to do, then stop listening to the fringe theorists who think they have natural ability. Trust the well-trained medical scientists. Your life, and your family’s life, may depend on it. At least, that's a possibility.