Bipolar Disorder

Mood Momentum in Bipolar Disorder

Mood shifts in bipolar disorder linked to disrupted neural reward circuits.

Posted July 29, 2024 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer

Key points

- Mood and emotion affect both what and how we learn and how we adapt to the environment.

- Disrupted neural activity in reward (striatum) and mood (insula) centers characterize bipolar disorder.

- Further exploration of the link between mood momentum shifts and RPEs might lead to new targets for therapy.

How would you define learning? When we learn something, there is a relatively permanent change in our behavior that comes about because of our experiences with the world around us. Learning allows us to adapt to the environment we find ourselves in successfully. So something that affects learning can affect how well we adapt.

Studies have shown that there are a number of factors that affect learning, ranging from what we have already learned (stored in our memories), to the environment we find ourselves in when we learn something new, to our social interactions, and even our socioeconomic status. An important factor that can affect how we learn, and even what we learn, is our emotions and our moods.

Paul Eckman, noted for his studies of human emotion, characterizes emotion and mood as differing along five dimensions. They differ in duration (moods last longer than emotions and can be difficult to get rid of), moods can make us more susceptible to experiencing a matching emotional response (a happy mood lowers the threshold needed to trigger the emotion of joy for example, and joy is more easily experienced when we’re already in a happy mood), moods tend not to have non-verbal expression while emotions are universally identifiable through facial expression, and finally, it can be difficult to identify the trigger for a mood, but usually easy to point to a trigger for an emotion (Eckman, 2024).

It's this last characteristic that had researchers Moningka and Mason (2024) interested in particular. They wondered about a question that has dogged clinicians and lab scientists alike for quite a while. This question has to do with bipolar disorder and the shifts in mood that characterize this emotional issue.

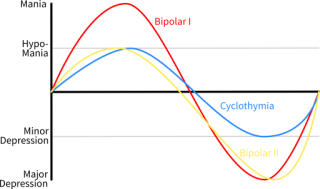

Biopolar disorder results in extreme shifts in mood, cognition and sleep, from emotional pole to emotional pole, extreme lows (depression) to extreme highs (mania). Luckily, bipolar disorder responds well to treatment and there are a number of effective treatments available. The question that has persisted has to do with what triggers the shift from one emotional pole to the other, and where in the brain this shift might be happening. Finding answers to these questions would be incredibly helpful in treating the disorder.

In their review of the literature, Moningka and Mason reported that there are many studies that have found that individuals suffering from bipolar disorder may be sensitive to rewards in a way that differs from that of non-sufferers. However, they also point out that there are as many studies showing a decrease in reward sensitivity in bipolar patients as there are suggesting an increase in reward sensitivity. They noted that this disagreement in the results might stem from two problems. The first is that making a decision based on the reward received is recursive, involving anticipation and expectation of reward, evaluation of the outcome of behavior, as well as other signals that affect the decision that will be made. One of these other signals that needs to be taken into account is the effect of mood on reward decision making.

When we learn something new, we make predictions about the reward we might receive. If the reward we get is better than our prediction then we create positive reward prediction error (Positive RPE) and our mood improves. This is, after all, what we wanted—a better than expected outcome. Our confidence increases, and we look for ways to repeat that rewarded behavior. If the reward is worse than our prediction, a negative RPE is created, which impacts mood in a negative direction. We lose confidence and will try to avoid the behavior that led to the disappointing outcome next time. These positive and negative RPEs can accumulate over trials in a learning task, pushing our mood up or down as we succeed or fail. Eldar, Rutledge, Dolan and Niv (2016) say that “Experiences affect mood, which in turn affects subsequent experiences. …First, mood depends on how recent reward outcomes differ from expectations. Second, mood biases the way we perceive outcomes (e.g., rewards), and this bias affects learning about those outcomes” (page 15). This bias is referred to as mood momentum.

Moningka and Mason examined fMRI recordings from participants with bipolar disorder and compared them to controls without the disorder. Recordings were made during a roulette task, under two different reward conditions. In the first condition the probability of reward was low (25%). The second had a 75% chance of reward. In addition, the recordings were made at three distinct time periods; making the choice about placing the bet, anticipating the outcome (while the wheel was spinning) and at the outcome itself.

They found that the change in mood created by the outcome of the spin of the wheel affected brain activity in reward and mood centers (ventral striatum and anterior insula) more strongly in participants with bipolar disorder than in controls. The connectivity between the ventral striatum (reward) and the anterior insula (mood) was also found to be disrupted in participants with bipolar disorder, suggesting that the momentum of mood might excessively bias the way the striatum tracks RPEs in bipolar participants in particular.

Further exploration of the link between mood momentum shifts and RPEs might lead to new targets for therapy.

References

Ekman, P. (2024) Mood vs. Emotion: Differences & Traits. https://www.paulekman.com/blog/mood-vs-emotion-difference-between-mood-…

Eldar, E., Rutledge, R.B., Dolan, R.J., and Niv, Y. (2016). Mood as representation of momentum. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(1), 15-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.07.010

Moningka, H., and Mason, L. (2024). Misperceiving momentum: Computational mechanisms of biased striatal reward prediction errors in bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry: Global Open Science, 100330 www.sobp.org/GOS.