Memory

Theta Waves and Human Memory

The way we take notes may influence how we remember.

Posted February 27, 2024 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- The way notes are taken in class (pen vs. keyboard) affects memory for the material.

- Writing with a pen has been linked to enhanced theta wave activity in the brain.

- Theta waves might be the glue that binds memory together.

Human memory is amazing. Psychologists who study memory have subdivided it into several memory types. First, there is sensory memory, or memory for information coming into the brain via a sensory system. Sensory memory lasts a very short time, on the order of milliseconds, and usually passes information along to other types of memory. Next in line, there is short-term memory (STM; sometimes referred to as "working memory"), which, as the name implies, is memory that does not last long (roughly 30 seconds unless we rehearse the information in it) and/or memory for information we need for what we’re working on at the moment. Both sensory memory and STM won’t hold on to information for long. To preserve the memory, we need to store it in the aptly named long-term memory (LTM).

Information in LTM can potentially last a lifetime. The capacity of LTM is also unlimited. There are two types of long-term memories stored in our memory vault. Memories can be implicit meaning the information is picked up along the way as we go through life, without our conscious effort engaged in storing it, like the memory for how to ride a bike. Explicit memory requires conscious effort to store, like remembering the order of the planets from the sun out. You had to apply effort to remember it.

Memory for facts and meaning are explicit memories, often studied and effortfully processed in school. As we read, talk, and write about the information presented to us in our classes, we are committing that information (sometimes imperfectly) to our explicit memories. And, as technology develops, the ways we can write down that information have also changed. Back when I was a student, we applied pen to paper to take notes, listening to the teachers and the rest of the class and making notes about what was being said, trying to summarize and organize the information. Now, largely in the interest of speed, students are leaning more and more toward note-taking on a laptop, a tablet, or even a phone.

And for those of us nostalgic for the good old days of writing it down, there is now evidence to suggest that there are neurological benefits to taking notes using your hands and a writing instrument (pen, pencil, or stylus to write on a screen) over clicking on keys on a keyboard.

Theta Waves and Memory

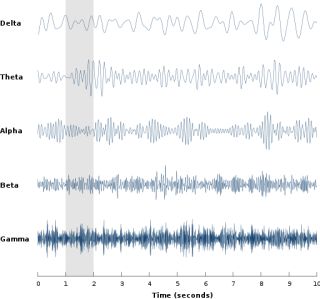

The benefits are related to how the brain goes about forming episodic memories. According to Clouter, Shapiro, and Hanslmayr (2017), “Episodic memories are information-rich, often multisensory events that rely on binding of different elements.” Disparate kinds of information from our sensory cortices are brought together, like a conductor brings the various parts of the orchestra together to create a complex symphony, by what are known as theta waves. Theta waves are rhythmic, low-frequency (four to nine waves per second) synchronized oscillations in brain activity. Research has shown that inducing theta rhythms in rat hippocampus (the brain region associated with memory consolidation) improves memory for a spatial task, and preventing theta waves impairs memory, again in a rodent (Berens and Horner, 2017).

Clouter et al., demonstrated that theta waves also had an influence on memory in humans. They asked participants to watch unrelated movie and sound clips and varied the luminance of the visual and the amplitude of the sound so that sound and light were either in or out of phase with one another, at frequencies that matched theta waves (variations in luminance and sound amplitude at four cycles per second). Matching the phase of the incoming information to theta wave frequencies induced theta waves in the brain. Participants were asked to remember the sounds paired with the movies. They found that memory performance for stimuli presented in phase with one another at theta range frequencies was better than when it was presented at either higher or lower frequencies. Theta waves appeared to be crucial for binding together at least these two forms of incoming sensory information into a long-term memory.

Askvik, van der Weel, and van der Meer (2020) found that taking notes by hand enhanced theta waves in the human hippocampus. Teenagers and young adults were asked to describe, copy, or draw a copy of a word or sentence, either with a digital pen on a screen or by typing using a keyboard. At the same time, electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings were made. They found that when a pen was used, brain regions in the parietal and central regions showed event-related synchronized theta waves. The parietal regions of the brain have been associated with processing both language and attention, making them prime candidates for a role in creating memories for new information. Typewriting was associated with desynchronized theta and alpha rhythms that were more widespread.

Clouter, Shapiro, and Hanslmayer (2017) argue that the creation of a memory involves the combination of inputs from all of our sensory systems and that the timing of the various incoming signals is extremely important to the creation of that memory. They have proposed that synchronized theta waves are the “glue that binds” these pieces of information and, so, our memories together.

So, for your next class, get that pen and paper ready.

References

Askvik, E. O., van der Weel, F.R., and van der Meer, A.L.H. (2020). The importance of cursive handwriting over typewriting for learning in the classroom: A high-density EEG study of 12-year-old children and young adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1810. Doi: 10.3389/fpsychg.2020.01810.

Berens, S.C., and Horner, A.J. (2017). Theta rhythm: Temporal glue for episodic memory. Current Biology, 27, R1108–R1129.

Clouter, A., Shapiro, K.L., and Hanslmayr, S. (2017). Theta phase synchronization is the glue that binds human associative memory. Current Biology, 27, 3143–3148