Circadian Rhythm

Circadian Rhythms and Your Health

How attention to your chronotype can help your health.

Posted January 29, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Physiological and psychological function are mediated by biological clocks.

- Chronotherapy can take advantage of these clocks to improve efficacy of drug treatment in chronic disease.

- The search is on for biomarkers that can help physicians create personalized chronotherapies for their patients.

Are you a night owl or an early morning lark? If your preference is for getting up bright and early and getting started as soon as your feet hit the floor, then you would be considered a lark. Owls, on the other hand, peak later in the day, perhaps finding it difficult to get out of bed in the morning, and staying up later at night. Breus (2016), disliking the dichotomous lark and owl distinction, proposed four chronotypes (defined as your natural preference for sleep and wakefulness at particular times of the day) rather than just the two; lion (the early riser), wolves (who prefer to rise late and stay up later), bears (who awaken slowly but then are raring to go), and dolphins (whose sleep pattern is irregular and often interrupted).

Regardless of your chronotype and preferences, for all of us, physiological processes like hormone secretion, reaction time, cardiovascular efficiency, body temperature, and even when we eat, happen in patterns throughout the day. These processes peak and ebb according to a biological clock within the cells that make up our bodies.

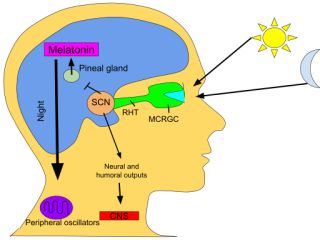

Nearly every cell in our bodies contains biological clocks, natural timing mechanisms that regulate the timing of many of our physiological and behavioral processes. These biological timers are coordinated by a master control clock found in a region of the hypothalamus called the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus or SCN. The SCN is itself influenced by the amount of available light in the world around us. The SCN receives incoming information about whether it is night or day, direct from the retina via ascending fibers of the optic nerve. The SCN then signals the body to wake up and get moving. For example, the SCN signals the pineal gland to reduce the release of the hormone melatonin, which makes us sleepy. The adrenal gland is also told to increase the release of cortisol, which makes us feel alert and awake. This process is reversed when the sun goes down, making us find a quiet and dark place to sleep, out of the way of predators. The SCN also modulates the cellular clocks that govern a myriad of other physical processes, linking our bodies and our minds to signals from the world outside us.

Circadian rhythms and our health

Being out of synch with one’s internal clock can have consequences. We all know that jet lag can make us tired and out of sorts as our internal clock tries to catch up with our flight plans. And shift work, working the night shift in particular, forcing us to be up and concentrating when our bodies are telling us to lie down and go to sleep, can produce the same disruptions in energy levels, cognition, and sleepiness that jet lag does. Trying to force a sleep-wake cycle that does not fit your chronotype can produce what is known as social jet lag—a discrepancy between the time as determined by our internal biological clock and social time, usually dictated by our social obligations like work and school.

Circadian rhythms and chronotherapy

Recent research shows that disruption of these rhythms can also have serious consequences for our health and well-being. Circadian rhythm disruption caused by working the night shift has been shown to moderately increase the risk of breast cancer in women and prostate cancer in men (Masri and Sassone-Corsi, 2019). This same study found that “late-eaters” (people who tended to eat late in the evening, after about 9:30 p.m.) also had a higher risk of both breast and prostate cancers. In addition, disruption of circadian rhythms and cancer go hand-in-hand. It appears that cancer cells can weaken and disturb the circadian clocks in the other cells of the body, even resetting their own circadian clocks compared to non-cancerous tissue.

The link between disruption of circadian rhythms and chronic disease has doctors investigating the potential link between cancer treatments and circadian rhythms. A new treatment approach called chronotherapy takes advantage of time of day to enhance the effectiveness of cancer treatment drug therapies. Chronotherapy is designed to time the administration of drugs to coincide with circadian rhythms in the cancer cells. Treatment is individualized to take advantage of the variability in circadian rhythms seen across people. In a 2021 review of chronotherapy research, the authors say that “chronotherapy aims to maximize anti-tumor effects and to minimize the toxicity of anticancer agents in normal tissue” (page 12). The search is now on for biomarkers that can help physicians create personalized chronotherapies for their patients.

References

Breus, Michael J. (2016) The Power of When, Little Brown and Co., Boston MA.

Masri, S., and Sassone-Corsi, P. (2018). The emerging link between cancer, metabolism, and circadian rhythms, Nature Medicine, 24, 1795-1803.

Panda, S. (2019). The arrival of circadian medicine, Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 15, 67-69.

Zhou, J., Wang, J., Zhang, X., and Tang, Q. (2021). New Insights into cancer chronotherapies, Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12: 741295, doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.741295.