Intuition

How to Take on a Challenge

What does it take to make the impossible possible?

Posted September 30, 2015

I recently met someone who used to eat competitively. You know, the Coney Island variety. He told me he began this culinary challenge back in high school. Instead of doing homework, he would dunk dozens of whole hotdogs in water and jam them down his throat as quickly as he could.

His personal record? Something like 24 hot dogs in 12 minutes. That's one hot dog every 30 seconds!

When I asked him why he did it. He replied with a smile:

"Because I could. And it's fun."

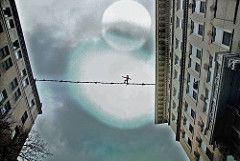

Then there's Philippe Petit, who famously walked across the World Trade Center towers (1350 feet above ground without a safety net) on a tightrope in 1974. When asked if he was nervous before the feat, he responded:

"I'm never nervous actually... I had no reason because it was my dream and I had thought of doing it for so many years."

Petit had been preparing for this moment (and many other equally impossible endeavors) since he had taught himself how to walk on wires at age 16.

In his TED Talk, he describes the arduous process of learning this new skill. What kept him going? He credits intuition as the "essential tool" of his life. Intuition allowed him to become his own teacher.

By the time he was 18, Petit had been expelled from several schools and spent most of the time inventing and mastering his moves. He quickly became an expert high-wire walker, but no one wanted to hire him.

Some might view this as an insurmountable obstacle. Not Petit.

Instead he decided to perform "in secret and without permission." His first stop was the Notre Dame in Paris. He rigged his wire without detection and then danced across the cathedral towers. He was 22.

Petit, despite his name, has always lived larger than life. He has spent his entire life making the impossible possible.

And he says that we can do the same.

How exactly?

Improvisation.

"Improvisation is empowering because it welcomes the unknown. And since what's impossible is always unknown. It allows me to believe I can cheat the impossible."

For Petit, his primary quest has not been success, but for the unknown.

In his latest book, Creativity: The Perfect Crime, he writes: "The creator must be an outlaw."

There are no limitations in his world. That's not to say there are no rules, however. Through his outlaw approach, he has developed his own set of creative principles, which include: solving problems intuitively, refusing failure, having a fanatical attention to detail and eschewing conventional values like competition, money or social status.

Most of us will probably never exercise this level of discipline in our lives; but then again, most of us are not Philippe Petit.

This is precisely the problem. The reason I have failed to make an impact on the world (of the caliber that I would like) is that I have convinced myself that I am not one of the greats. I am not Philippe Petit. I am not Steve Jobs. I am not Picasso.

When in reality, these larger-than-life figures likely began their journeys never setting out to be the best or to be among the greats. Remember, Petit didn't believe in comparing himself to others. He simply did what he did because he wanted to and he could. (And failure wasn't an option.)

I've always wanted to be a great writer. You could say this has been a (somewhat dormant) passion for the last decade or so. I've written for newspapers and magazines (I even went to a j-school to learn how to write better), but I have never quite felt like I was a great writer.

Lately, that feeling has grown into a severe case of writer's block. I remember when there used to be no shortage of material to write about—to think about, to question—but now, it seems I've settled into this lackluster routine of being a boring adult that just goes to work and watches too much Netflix. My thoughts are no longer my own.

Instead I indulge in other people's fantasies.

In other words, I am not an outlaw. I am a perpetual law abider. I have never been expelled from anything (although I did get suspended once for wearing a mid drift shirt in middle school—the single transgression of my entire educational existence). And when something gets difficult, I quit. Not only is failure an option, it is often my go to.

I don't know how to change a mindset like this. But researchers Ulrich Weger and Stepehen Loughnan do.

According to them, your thoughts can actually shape your abilities.

"[They] asked two groups of people to answer questions. People in one group were told that before each question, the answer would be briefly flashed on their screens—too quickly to consciously perceive, but slow enough for their unconscious to take it in. The other group was told that the flashes simply signaled the next question. In fact, for both groups, a random string of letters, not the answers, was flashed. But, remarkably, the people who thought the answers were flashed did better on the test. Expecting to know the answers made people more likely to get the answers right."

Thinking we can do better makes us do better. And conversely, simply thinking that we are limited is precisely what limits us.

There have been similar outcomes from studies testing vision and weight loss.

What this research seems to suggest is that the challenge, the hard part, the difficult stuff just lives in our heads.

I spoke with a spiritual healer recently who told me that my lack of writing was due to the fact that I no longer had any fun with it. I had been so obsessed with wanting to write something worthy of greatness, that if my thoughts weren't great, there was no point in writing them down.

He was right. Writing had stopped being enjoyable. There was Zero Enjoyment, to be honest. Just an inordinate amount of pressure to get it right. Write that million-dollar screenplay, Pulitzer-prize winning novel, or billion-view blog post.

I forgot how to enjoy writing. I forgot how much I loved translating stories from my head to paper. I forgot the goosebumps I would get when writing something so shockingly poignant that I couldn't even believe those words lived in me. I forgot that it used to be my favorite thing in the world to do.

Intuition. Improvisation. Passion. Tenacity. Positive mindset. Yes, you need all these qualities to achieve something extraordinary. But like the hotdog eater said, I think you also need to have some fun.

Follow me on Twitter: @thisjenkim

Want to get an update when I write a new post? Sign up here.