Bias

Black History and the Filipin@ Community

Our struggles with colorism, racism, and the legacies of colonialism.

Posted February 10, 2016 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

As we honor and appreciate the historical and modern-day contributions of African Americans to this country, I cannot help but to also be reminded of the painful reality that many of my fellow Filipin@s—many among the 3.4 million in the United States, the 98 million in the Philippines, and the few million more in the rest of the diaspora—still hold deep prejudices against people of African descent.

Yes, despite the fact that Filipin@s all over the world continue to be discriminated against because of their heritage—for example, 99% of Filipin@ Americans experience racism on a regular basis—many Filipin@s still continue to not see their connectedness with our African American brothers and sisters. Many Filipin@s today still continue to hold anti-Black prejudices.

So let’s break down these ingrained anti-Blackness attitudes a little bit.

Colorism, Racism, and Colonial Mentality in the Filipin@ Community

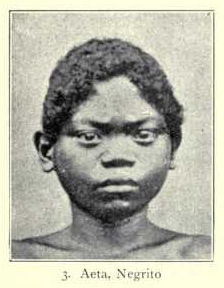

The continuous marginalization of the Aeta people—one of the Philippines’ Indigenous Peoples who have African roots—and the discrimination they face from dominant Filipin@ ethnic groups (e.g., the Tagalogs, Kapampangans, Ilokanos, etc.) who regard them as uncivilized, uneducated savages, is just one example. The deeply ingrained colorism among many Filipin@s—with their automatic regard of lighter-skin complexions as being attractive, desirable, or higher class and automatic relegation of darker-skinned people to being ugly, undesirable, or poor—is another clear example. The abundance of skin-whitening clinics in the Philippines and the high rates of using skin-whitening products (e.g., lotions, soaps, creams, tablets) among Filipin@s—in the Philippines and in the United States—is further evidence of this fear of dark complexions that is held by many naturally-brown Filipin@s. The fact that many Filipin@s discourage their children, relatives, and friends from being romantically involved with or marrying Black people is yet another manifestation of this widespread anti-Black attitude in the Filipin@ community.

These attitudes, prejudices, and behaviors that are widespread in the Filipin@ community that operate to dehumanize and inferiorize other peoples of color—including fellow Filipin@s who are darker-skinned or perceived to be not Westernized or Americanized enough—are examples of what has been called lateral oppression or within-group discrimination. In other words, oppression comes to infiltrate peoples of color that they begin to oppress themselves and others like them. Lateral oppression or within-group discrimination is one manifestation of internalized oppression—or colonial mentality as it is more popularly called in the Filipin@ community. Research suggests that internalized oppression or colonial mentality has negative effects on peoples of color’s psychological well-being and mental health.

So we need to resist oppression’s attempt to divide and conquer us. We need to resist the internalization of oppression that leads us to buy into the notions of colorism and racism, which leads us to have stereotypical, inferiorizing, and dehumanizing attitudes toward African Americans and dark-skinned individuals. Maybe learning a bit more about the ties between African Americans and Filipin@s will help us with this resistance.

Historical Connections Between African Americans and Filipin@s

As Filipin@s—as peoples of color—in these United States, we need to acknowledge that we owe plenty of the freedoms and privileges that we enjoy today to the struggles, leadership, and activism of African Americans. To support this point, it is easy to simply refer to the obvious truth that a large reason for why Filipin@ Americans are able to live the life we have today as peoples of color in this country is because of the work of our Black brothers and sisters that led to the victories of the civil rights movement.

However, I believe that Filipin@s’ appreciation of Black contributions to this country—historically and contemporarily—need to go beyond the civil rights movement. This is because the connections between African Americans and Filipin@s go way deeper and farther than this. Such a meaningful connection between African Americans and Filipin@s has been largely unseen and unheard, and it has to be told.

For example, not very many people know that thousands of African American male soldiers who were stationed in U.S. military bases in the Philippines until 1991 fathered children with Filipina women. Indeed, an estimated 25% of the approximately 52,000 “Amerasians”—mixed-race children of American soldiers with Filipinas—have African American fathers. The U.S. Congress passed a law that allowed Amerasian children born in Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos to immigrate to the U.S., but this law did not apply to Amerasians in the Philippines. So the only pathway for Filipin@ Amerasians to become citizens, even though they should have already been automatically considered as U.S. citizens given that their fathers are U.S. citizens, is if their fathers file paternity claims before they turn 18 years old. But because the U.S. military bases in the Philippines closed 25 years ago when the U.S. soldiers hurriedly left, most of the children today are already too old to claim citizenship or to be claimed by their fathers. In other words, there are approximately 13,000 mixed-race Filipin@-African American individuals in the Philippines today who have been abandoned and whose rights as Americans are not recognized!

Going back further, not very many people know that Carlos Bulosan—probably the most influential Filipin@ American poet and novelist in United States history who wrote prolifically about his experience as a Filipino man in America during the early to mid-1900s—related the struggles of early Filipin@s in America to those of the struggles of African Americans (and other groups). For instance, in his most famous work “America is in the Heart: A Personal History,” Bulosan wrote:

“America is not a land of one race or one class of men. We are all Americans that have toiled and suffered and known oppression and defeat, from the first Indian that offered peace in Manhattan to the last Filipino pea pickers. America is not bound by geographical latitudes. America is not merely a land or an institution. America is in the hearts of men (and women) that died for freedom; it is also in the eyes of men (and women) that are building a new world. … America is also the nameless foreigner, the homeless refugee, the hungry boy begging for a job and the black body dangling from a tree. America is the illiterate immigrant who is ashamed that the world of books and intellectual opportunities is closed to him. We are that nameless foreigner, that homeless refugee, that hungry boy, that illiterate immigrant and that lynched black body. All of us, from the first Adams to the last Filipino, native born or alien, educated or illiterate — We are America!”

Going back even further, not very many people know that there is a strong and meaningful connection between the struggles of African Americans against American racism and the struggles of Filipin@s against American imperialism. For example, many African American soldiers during the seemingly forgotten and never-talked-about war between the Philippines and the United States from 1898-1913 sympathized with the Filipin@s who were fighting to keep their sovereignty and independence. As noted Filipin@ American scholar and historian Yen Le Espiritu wrote:

“White American soldiers in the Philippines used many of the same epithets to describe Filipinos as they used to describe African Americans, including ‘niggers,’ ‘black devils,’ and ‘gugus’ … If we positioned Filipino/American history within the traditional immigration paradigm, we would miss the ethnic and racial intersections between Filipinos and Native Americans and African Americans as groups similarly affected by the forces of Manifest Destiny. These common contexts of struggle were not lost in African American soldiers in the Philippines. Connecting their fight against domestic racism to the Filipino struggle against U.S. imperialism, some African American soldiers – such as Corporal David Fagen – switched allegiance and joined the native armed struggle for independence” (p. 52).

Toward Filipin@ Solidarity With the African American Community

Indeed, there are many historical and modern-day realities that tie the African American experience and the Filipin@ experience together. Perhaps by becoming aware of the long and meaningful connections between African Americans and Filipin@s, then maybe we can begin to address the pervasive anti-Black sentiments in the Filipin@ community. Perhaps by becoming aware of such historical connections, then maybe more Filipin@s will become aware of our own history of colonialism and oppression, the legacies of which include the colorism and racism that still negatively affects how we look at ourselves, African Americans, and other peoples of color today.

Perhaps by becoming aware of such historical and contemporary connections with the experiences and struggles of the African American community, then maybe the appreciation and celebration of Black contributions will be more pervasive in the Filipin@ community.

Perhaps more Filipin@s will be in solidarity with our Black brothers and sisters as we resist oppression and create social change—together.

Follow me on Twitter.