Law and Crime

From the "Crime of the Century" to a Trial Obsession

How the 1920s' Leopold and Loeb murder case inspired me to be a writer.

Posted March 6, 2020 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

When I think about my life, I think about loss, and I think about murder.

My biological father died when I was 2 weeks old. But when I was three, my mother married the man who became my stepfather. A quiet, unsmiling man, it was he who introduced me to the obsession that shaped my life.

My stepfather had grown up with the millionaire families of Chicago’s two famous murderers, Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, and their victim, 14-year-old "Little Bobby" Franks.

I was around 8 or 9 when my stepfather said: "Everyone knew it was my younger brother, Tilden, and not his classmate, Little Bobby Franks, whom Leopold and Loeb really meant to kill. Tildren would have been killed," my stepfather added. "But that day the chauffeur picked him up early from school because he'd caught a cold."

Leopold, 19, and Loeb, 18, had committed their murder in 1924—a decade before I was born. But I grew up fascinated by my stepfather's and his friends' ongoing talk about this "Crime of the Century." I became just as riveted on hearing about the defense by legendary Chicago defense lawyer, and noted capital punishment foe, Clarence Darrow, in Leopold and Loeb's "Trial of the Century."

Sometimes at night I'd think about details I’d heard about the case. In the 30s and early 40s, a time of rampant anti-Semitism, people still wondered how two allegedly brilliant, wealthy Jewish boys from such nice families could have carried out such a callous, long-planned act—“not for money, not for spite, not for hate,” as Darrow memorably said. Instead, inspired by Nietzsche to prove they were supermen, they targeted Bobby Franks on a whim, before bashing him to death with a chisel in a rented car.

But they didn’t get away with it. Thanks to a unique pair of glasses Leopold lost while he and Loeb tried to hide the body, they were caught and confessed in just over a week.

Theirs was the first trial in the country based on psychiatric testimony, in which experts offered insight into possible reasons for the killing. Doctors implicated the then-unthinkable homosexual relationship between Leopold and Loeb. They testified that Leopold had helped Loeb carry out felonies he wanted to commit (fire-setting and theft), in exchange for Loeb's granting sexual favors that Leopold desired. Psychiatrists traced this pact to warped childhood fantasies that sprang from the strict, but sometimes sexually provocative behavior of Leopold and Loeb's governesses. Experts also incriminated the killers' alleged glandular disorders, and discrepancies between their emotional and intellectual lives as other murder causes.

The judge ignored this confusing, often nonsensical-sounding testimony. He ruled that punishment should be mitigated, or tempered, not, as Darrow had pled, by Leopold and Loeb's alleged mental disease, but by their youth. Consequently, in line with Darrow's hope, but not his argument, the judge sentenced the pair to life imprisonment instead of to death.

As I grew older, I thought I too could understand some reasons for the murder. Like Leopold and Loeb, my family also had strict European-born maids, nurses, and governesses, and my apartment rang not so much with laughter, but with threats. “You’re a bad girl, and you’ll be punished.” Or “You lied about eating that Hershey bar. You will be spanked if I tell your parents.” Even catching a cold was 'bad', as if it was my fault.

"Good." "Bad." There was nothing in between. Plotting to circumvent my parents’ rules and prohibitions became a way of life for me. I later read that like me, Leopold, as a child, had also chafed at having been infantilised. Seething with my secret rage, I felt I could understand the anger and hatred that must have fueled the young duo’s murderous drives.

In school, our class studied Darrow's moving three day summation. The summation left me moved too. But I couldn't help boast about my family's thrilling connection to the murder.

Only I didn't bask long in any Tilden-conferred notoriety. "No, it was my uncle John who was the intended victim," a friend would say.

“No,” another friend would insist. “Leopold and Loeb really planned to murder my Uncle Bob!”

I soon learned why I kept being contradicted. In their months of planning, Leopold and Loeb admitted having kept a hit list of potential boy victims in many of their ultra-rich neighborhood families.

My stepfather dismissed all rival claims to fame. This was because Tilden actually had died, not long after Little Bobby Franks. He was killed at 20 when he was a college student, in a head-on automobile collision.

My stepfather’s pale blue eyes would grow frosty with grief over the two seeming premature deaths of Tilden, and the one of Little Bobby Franks. “Leopold and Loeb should have paid with their lives for what they did,” he’d say. “They were terrible people who did a terrible thing for which they should never be forgiven."

I was still in grade school when I learned of another, surprising family connection to the murder.

“You know who that man is, don’t you?” my friend Helen asked me one Saturday afternoon. She pointed into the living room where my stepfather sat hunched at a card table with some of his bridge-playing friends. “He’s Nathan Leopold’s younger brother.”

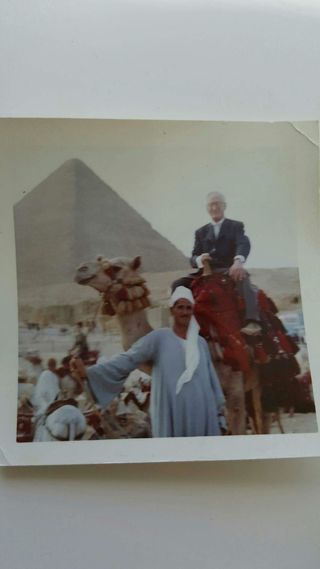

My stepfather said it was true. Amazingly, he told me this close friend had for years driven miles to visit his brother in the state penitentiary in Joliet, Illinois. My stepfather and this friend , like all of his friends, clad in their everyday attire - their silk Sulka ties and impeccably pressed, delicate cashmere suits - appeared nearly identical. I couldn't imagine any of them setting foot in a prison. As seen in an old family photo, this was my stepfather's attire even when riding a camel in the Egyptian desert, a pyramid looming in the background, while beside him, his indigenous guide stands clad in the thousands-year old garb of desert nomads.

In high school, I grew more intrigued by our family’s Leopold and Loeb connections. That's when Nathan Leopold’s niece and nephew moved with other friends of my parents, their mother and stepfather, into our apartment building in Chicago.

The dark-eyed nephew looked exactly like pictures of his uncle I’d stared at in Life magazine. But the niece, a few years older than me, was the most vivacious and popular girl I’d ever met.

During periodic elevator rides up and down in our building, I’d grow stiff and tongue-tied in the blazing light of her presence. Shy and self-conscious, I felt I would have made a more suitable Leopold niece.

In his trial summation, Darrow said he hoped that one day, when they were middle-aged, Leopold and Loeb might be freed.

Loeb was slashed to death in prison after serving just over a decade of his sentence. But when I was in high school, Leopold, aided by a new lawyer, began battling to clear his name and win release.

Like other World War II prisoners, Leopold had volunteered to be a guinea pig in painful and risky malaria treatments. He’d also helped reorder the prison library system, taught classes to inmates, worked as an x-ray lab technician and psychiatric nurse. In addition, he’d mastered many languages, become a noted ornithologist, and had also written a book expressing remorse for the killing. Professors with whom he’d studied, as well as celebrities, from Eleanor Roosevelt to Chicago poet Carl Sandburg, traveled to Springfield to plead his cause to the governor.

At home, I also argued that Leopold deserved to be paroled. My stepfather, who didn't give a hoot for these leftist celebrities, still insisted that Leopold should never be freed.

I was in my mid-20s, mother of a newborn son, when Leopold, after serving 33 years of his life plus 99-year sentence, finally won parole. Unlike ostracized relatives of other infamous criminals, the stricken principals in this case had retained their their friends. I learned that my stepfather spent the day of Leopold’s parole hearing with friends, including many Leopold and Loeb family members, on the golf course of their exclusive suburban Lake Shore Country Club. The men all feared that once freed, Leopold might be allowed to join the country club.

Unlike relatives of notorious killers today, who vie for book rights, and bet on who will play whom in the inevitable film about the case—Leopold’s family forbade him from giving speeches or granting any radio or TV interviews. They sent him to live in Puerto Rico, where he became a social worker and eventually married. His nephew, my former neighbor, told me that later, Leopold occasionally did travel to Chicago. There, he visited the graves of his deceased parents, dined with old friends, and peered over the still-forbidden grounds of Lake Shore Country Club. Like other Leopold men, he died young, of heart disease, at age-66. People were surprised that Leopold had kept a photo of his long-mourned "best friend," Richard Loeb, in his bedroom.

Leopold's death left me feeling unmoored. But his absence also spurred me belatedly to become the writer I'd always wanted to be. Not just any writer—I wanted to report about famous trials. I was a mother of four nearly grown children when I finally applied for and received a New York City press pass and began my new Leopold and Loeb–inspired career.