Gender

Fathers: Heroes, Villains, and Our Need for Archetypes

Why do we want our leaders to be our fathers? Some archetypes persist.

Posted May 31, 2018

When the first plane hit the World Trade Center in Manhattan, I was standing on a pier in northern Wisconsin. The day couldn’t have been lovelier. Or more serene. A clear blue sky, the light gloriously golden on a perfect fall day.

The summer folks had left the lake by then. The quiet, for this working author, was a balm. Then the phone rang. It was my husband telling me that a plane had crashed into one of the towers. They did not know what had happened yet, he said, but probably something was wrong with the plane. He told me not to worry and to go back to my writing.

We had no television at our cabin. As soon as I hung up, I turned on the radio. Ten minutes later, the second plane hit. It was the beginning of a national trauma. I immediately packed and began the four-hour drive back to Madison.

Here is where fatherhood comes in. During that entire ride home, I kept the radio on, waiting for my President’s voice to assure me that this was not the end of the world. I later learned that George W. Bush did broadcast a brief statement from the school in Florida where he had been reading to children. But for some reason, I never heard it on my radio.

The silence I experienced from our president during those long anxious hours driving home has stayed with me. I was reminded of how FDR’s inspiring words after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor not only shaped America’s destiny but reassured an entire nation of its strength and purpose. Churchill in Britain during the blitz, Gandhi in India fighting for independence from colonial rule, Mandela in South Africa—these are the associations that come to mind when we think of national heroes as strong father figures. To be sure, the same human flaws afflicted them that afflict the rest of us, but over time idealized versions of these men persist. They have come to represent the virtues of courage, fortitude, wisdom, and benevolent authority—values that most cultures deem positive and necessary for the continuation of the state.

On the day of the 9/11 attack and during the months that followed, I found myself longing for just such a father figure, one who could assure me that not only did our government have the skills and wisdom to deal with the frightening prospect of terrorism, but also that I could continue to believe in our common humanity and our democratic institutions.

The projection of values onto a national figure parallels how we project values and qualities onto the most important and guiding presences in our personal lives, our own mothers and fathers. What is projected or placed onto another individual by our unconscious reflects the values of our specific time and place as well as our psychology. A child growing up in eighteenth-century England, for instance, could expect a model of fathering quite different from a child growing up in eighteenth-century Polynesia. Likewise, today, the diversity of fathering styles emerges from the diversity within a culture.

Yet, certain eternal structures within the human psyche–archetypes–exist across cultures and transcend time and place. In The Father: Contemporary Jungian Perspectives, psychoanalyst Andrew Samuels notes that the archetypal father is not restricted to personal experience: “The idea is that, behind the personal father whom we know and to whom we relate, lies an innate psychological structure which influences the way we experience him.”

In classical Jungian terms, the mother archetype is characterized by nurturing, containing, and generative qualities, while the father archetype is assumed to be a more active and aggressive principle dominated by intellect and will. This duality, which current gender issues may question, is nonetheless reflected in our myths and language, and our view of the cosmos. We say Mother Earth (Gaia), Father Sky (Kronos, Zeus, Yahweh); we speak of Eros (Soul) and Logos (Spirit). During the Third Reich, Nazi propaganda favored calling Germany the Fatherland (Vaterland). By contrast, Russians often refer to their country, affectionately, as the Motherland. Why a country should be referred to as one parent or the other may represent our differing expectations of mother and father. The former implies care, belonging, family, benevolence; the latter, order, discipline, masculine strength.

Not every male leader who becomes a father figure is a hero. An alarming number of kings, dictators, presidents, and the like, embody the shadow qualities of the archetype. Historians have accounted for Hitler’s rise to power by his uncanny understanding and manipulation of the desperation and dissatisfaction of many German citizens. If his determination to restore Germany to its former glory won him adoration as a worthy and strong father figure, his inhumanity toward Jews and others expressed a collective need to blame others/outsiders for the country’s troubles. Cult leaders such as Jim Jones, Charles Manson, or David Koresh also took on the status of father figures, playing out on a grand scale the violent, destructive, and anti-social aspects of the father archetype. These men are our abusive fathers writ large.

Whether we think of our fathers as heroes, villains, or just ordinary guys, they (or father substitutes) play a crucial role in our psychological development by presenting a crucial and necessary complement to the bonding relationship with mother. Mothers provide the breast for nourishment, but in our ancestral history fathers were necessary to ensure the survival of offspring. They provided protection from predators and alternative sources of food. In the postmodern world, most mothers work, whether tending crops or in an office. Father as sole breadwinner is no longer an accurate description of his family role. On their website, Parents As Teachers, William Scott and Amy De La Hurt cite the following research on the important role of fathers in raising young children.

- Early involvement by fathers in the primary care of their child is a source of emotional security for the child (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011).

- Fathers’ affectionate treatment of their infants contributes to high levels of secure attachment (Rosenberg & Wilcox, 2006).

- Children who have close relationships with their fathers have high self-esteem and are less likely to be depressed (Dubowitz et al., 2001).

- When fathers acknowledge their child’s emotional response and help them address it with a problem-solving approach, the children score higher on tests of emotional intelligence (Civitas, 2001).

Fatherhood and fathering are receiving more attention from psychologists these days. Economic and sociological changes, more working mothers, more single mothers among them, have put many fathers in the role of primary or shared-time caregiver. Decades ago, a father in the delivery room was unheard of. Now it is a common practice. Fathers can participate in the pregnancy through classes and instructions on everything from birthing techniques to the specifics of breastfeeding. Cultural changes concerning gender identity and same-sex marriage will continue to precipitate changes in how we parent.

In many places around the world, people believe their parents live on as spirits after they’ve died. Through ritual and ceremony, these wisdom figures return to the living to offer advice, supply ancestral memory, or intervene with the gods. For some of us, our fathers have become inner figures who aid and support our journey into maturity. On the level of inner development, we can work with forgiveness and compassion, and form a new relationship to a father who may have been a source of pain. Absent or present, dead or alive, our fathers have shaped who we are.

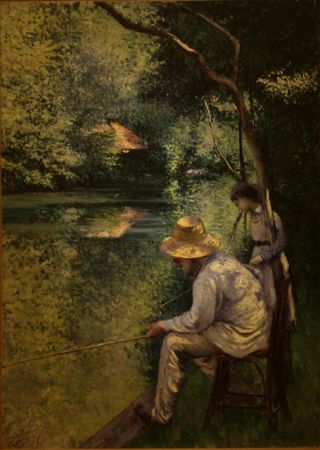

Here is a beautiful poem by Robert Hayden, written by a son, now a grown man, remembering his father with love and remorse.

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with crack hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

I’d wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he’d call,

and slowly I would rise and dress

fearing the chronic angers of that house,

Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love’s austere and lonely offices?