Personality

When Partners' Personality Styles Clash

Partners can learn to work with their differences and create harmony.

Posted April 14, 2021 Reviewed by Chloe Williams

Key points

- Different styles of functioning can, but need not, cause problems in marital and other intimate relationships.

- Deciding that our own style of functioning is objectively better than our partner's can worsen conflicts.

- Acknowledging the range of possible styles of functioning and each partner's place on the spectrum can help couples work through conflicts.

There are many relationship problems this post is not about, namely problems related to serious psychopathology, abuse, addiction, infidelity, or a basic lack of attraction. This post is about a common, ordinary type of couples' problem: the type that occurs between two good, functional people whose personality styles clash in some way.

Different Does Not Mean Better or Worse

Differences in styles of functioning play a role in many marital and couples problems (Shapiro, 2020a; 2020b). He is a morning person, and she is a night person; she wants more closeness, and he wants more autonomy; he is dramatic and expressive, while she is understated and reserved; one partner wants to discuss problems extensively, while the other wants to move on quickly, and so forth.

Differences in styles of functioning, in and of themselves, are not problems. Couples become angry and unhappy when they misunderstand their differences to be disagreements about some objective issue in the category of "how things should be done."

Sometimes couples come to therapy with the agenda of convincing their partner of this truth, and they hope the therapist will solve the problem by judging their preference to be right and getting this across to their partner (e.g., “Maybe if you say it, she’ll believe you”). This stance is often signaled by questions to the therapist taking the form, “Don’t you think people should ___________ (e.g., “talk things out until they’re done” or “move on once an incident is over”)?

When I listen to couples debate, my thought process often goes something like this: “She has such a strong point…. Oh wait, he has a good point too…. That example really supports her position…. But how could she have done that…. Oh, he left that part out…. Shoot, there’s no logical right or wrong to this, it’s just a matter of degree.”

Turning Binaries Into Spectrums

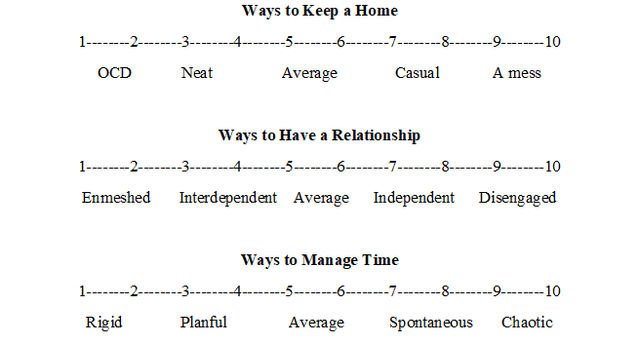

As my internal pendulum swings back and forth depending on who is talking, the swings often coalesce into an image of a spectrum. The spectrum shows the range of possible styles related to the issue in question. Invariably, the two members of the couple have styles on opposite sides of the continuum—that’s why they’re fighting. Here are three examples:

In spectrums like these, each side summarizes one half of a two-sided issue; in a sense, each personality style reflects one half of the truth. There is value in closeness, and there is value in autonomy; it’s good to discuss problems, but sometimes it's best to move on, and so forth. Logic cannot resolve these debates because both sides are half right. What’s needed is a different paradigm.

The word “dialectical” in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) refers to the idea that opposite truths can co-exist. Couples can advance to a more constructive level of discussion when they recognize that their partner’s truth does not refute their own, nor vice versa. Rather than battling over principles when both principles have validity, we can ask the standard DBT question, “What else is true?”

If you want to use a 10-point scale to understand and improve your relationship, the first step is to identify the dimension of functioning on which you and your partner’s conflicting styles are located. Your entire personalities aren’t in conflict (you wouldn’t be together if they were), but perhaps some aspects are.

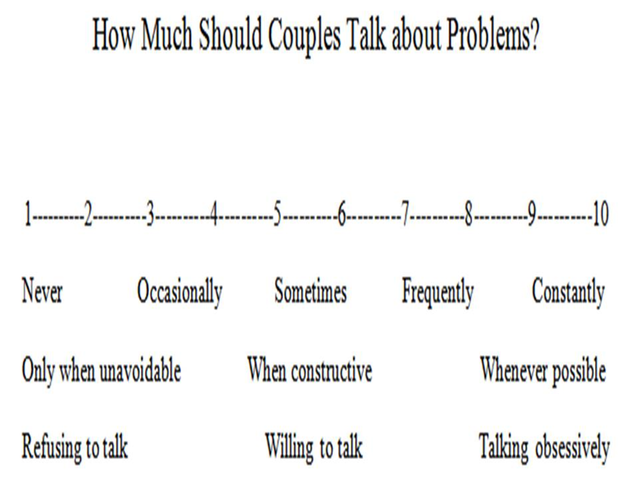

Spectrums are defined by their poles. So, for the 1-2 and 9-10 regions of the scale, think of words that describe extreme versions of the two opposite qualities. For the intermediate regions (3-5 and 6-8), think of words that describe milder, more moderate versions of these opposite qualities. Here is an example of a continuum that emerged from one couple's discussion:

Now you and your partner can indicate where you think you both are on the spectrum. There will be a total of four answers. If it’s hard to decide between two numbers, use a fraction or decimal.

You and your partner will probably disagree about the ratings. That’s not a problem. The purpose of the exercise isn’t to get you to agree but to work toward mutual understanding and harmonization of the styles.

The next step is to discuss the advantages and disadvantages associated with each side of the continuum. This step is important, and it can always be done. If you don’t think there are any advantages to your partner’s side, ask what they think the benefits are, and you will learn something about the reasons for their behavior. At the extremes of spectrums, disadvantages outweigh advantages, but moderate versions of personality styles always have adaptive value.

How to Depolarize a Disagreement

Much couples work hinges on the difference between spectrum extremes (1-2 and 9-10), which suggest dysfunction, and intermediate ranges (3-5 and 6-8), which describe distinctive but reasonable ways of behaving. When couples are in conflict, they usually perceive each other’s styles as extreme—and these perceptions are often inaccurate.

Here is an example of a disagreement in which both partners perceived the other’s style to be at the end of a continuum, while both believed they themselves were in the mid-range:

SHE: When there’s a problem between us, you want to talk about it for hours, until I feel like I’m drowning in words.

HE: I don’t want to talk about problems “for hours,” I want to talk about them until they’re resolved. I can’t do that when, after one minute, you say we’re going to have to wrap this up.

SHE: I am perfectly willing to talk about problems for more than one minute…

Here is a translation of this exchange into spectrum terminology:

SHE: When there’s a problem between us, you’re a 10 (“for hours”).

HE: I am not a 10, I’m a 7 (“until they’re resolved”). I can’t make that work when you’re a 1 (“after one minute”).

SHE: I am not a 1, I’m a 4 (“willing to talk”).

She said he wants to talk about problems for hours, and he said she won’t talk for more than one minute. It is unlikely the couple is truly this far apart on the subject in question; their perceptions of each other are probably exaggerated and distorted. This is polarization, and it drives people farther and farther apart.

Depolarization can be achieved by using 10-point scales as a tool. When the discussion becomes quantitative, mutual perceptions become more careful and accurate, and this generally reveals that couples are not as far apart as they thought. Also, recognizing the elements of validity on the other side of the spectrum moves couples closer together and replaces dissonance with harmony (Shapiro, 2020a; 2020b).

Most styles of functioning have advantages and disadvantages. Acknowledging this can transform angry battles about black and white into nuanced discussions of shades of gray. Rather than arguing about whose way is better, we can have constructive conversations about how to harmonize our personality styles and find more comfortable ways of being together.

Behaviorally, harmonization can mean several things. It can mean a compromise in which both partners move toward each other on the spectrum, although not necessarily meeting in the middle. It can mean moving around the spectrum together, using different styles at different times depending on the situation. And it can mean letting the contrasting styles continue but, rather than getting upset about the differences, using them to provide complementary forms of value, so they balance each other out.

To conclude with some of our examples, harmonization could mean a morning person going to sleep later and a night person going to sleep earlier, while sometimes taking a break from coordination and reverting to their natural schedules. It could mean an intensely expressive person talking in a softer, calmer voice while his reserved partner changes the way she interprets a given decibel level. It could mean figuring out how to talk about problems the right amount, perhaps by identifying when the point of diminishing returns has been reached. Couples who blend their different, complementary styles become wholes that are greater than the sum of their parts.

References

Shapiro, J. (2020a). Psychotherapeutic diagrams: Pathways, spectrums, feedback loops, and the search for balance. Amazon Digital Services.

Shapiro, J. (2020b). Finding Goldilocks: A guide for creating balance in personal change, relationships, and politics. Amazon.com Services.