Relationships

Emerging Adulthood: The Twenty-Something Stage of Life

All grown up but not ready to commit.

Posted March 11, 2018 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Adolescence is a liminal stage—it is the transitional threshold between childhood dependence and adult responsibility. The hard part is knowing when you've arrived.

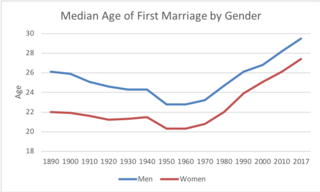

That questioning sentiment seems pretty common among 20-somethings right now: both my sons were recently gifted T-shirts on that theme. Although one can argue that historically the transition from childhood to adult responsibilities was long, uneven and muddled, certainly in the mid-century United States it was pretty clear: you became an adult when you (1) finished school, (2) got a job, (3) married, and (4) had children. Not only was that temporal transition relatively short during the decades when the age of marriage for women hovered just above 20, but it was also relatively tightly sequenced. Social institutions tended to support people who moved through it in order. Things were a lot tougher for people who did not.

In the decades since, several societal changes have stretched the transition to adulthood out and loosened the sequence. School has become increasingly extended. Although most adolescents finish high school and go on to college, only 59% of those who start a bachelor's degree finish within six years. For those starting at open-enrollment institutions such as community colleges, that rate falls to 32%. Working during college has become normative. As the age of marriage has risen from mid-century, many more people are having children prior to marriage, further complicating the transition to adulthood as people work to combine roles—for example, dating partner and parent—in ways that are not yet clearly defined.

Emerging Adulthood: Jeffrey Arnett has argued that these cultural changes have resulted in a new life stage between adolescence—what had been traditionally been defined as a state of preparation and socialization—and adulthood. "Emerging adulthood," he argues, is a normative life stage characterized by:

- diverse experiences

- lack of long term commitments

- unstable romantic relationships and employment

The popular press tends to focus on the lack of commitment and instability of romantic relationships and unemployment of emerging adults. For developmentalists, it may be the diversity of the period that is most controversial. If I talk about U.S. 15-year-olds, I can assume most of them will be in school and living with parents. If I talk of 50-year-olds, most will be or have been in long term romantic relationships, working, with children. Most 80-year-olds are retired. But 20-somethings? They could be married with children, in graduate school, working 60 hours a week and too busy to date, or a single parent working two jobs. The diversity of this age group is striking.

Two other striking characteristics of this group are that although they are legally and cognitively adults, they have often yet to take on the roles most closely associated with adulthood: employment, marriage, and parenthood. When they do take on those roles—as many people in their 20s do—we no longer talk about them as 'emerging adults.' We just call them adults.

Emerging adulthood, seemingly, ends when people make commitments and decide to take on traditional roles. It's not like childhood, which ends on our thirteenth birthday.

The challenges of emerging adulthood

As many struggling twenty-somethings will tell you, freedom to explore has both advantages and costs. Emerging adults use mental health services at high rates than those older or younger than themselves. They have more mood disorders, greater anxiety, and higher rates of substance use.

Though many struggle to prepare themselves for gainful employment, it can be difficult for young adults to establish stable careers. The average emerging adult will experience eight job changes between 18 and 29 and experience at least that many changes of romantic partners. Change, for many, is stressful.

On the other hand, this is a decade characterized by optimism—change can also be change for the better. Emerging adults typically describe their future as one of possibilities and are optimistic about their long term success. One of the advantages of having few ties is the freedom to explore. This decade is typically seen in which youth spend relatively less time helping others and more time focusing on themselves.

References

Arnett, J. J., Zukauskiene, R., & Sugimura, K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18-29 years: implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569-576. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(14)00080-7.