Memory

Using Psychology to Boost Your Grades: Taking Notes

Note-taking isn't about transcribing, it's about processing information.

Updated February 5, 2024

Many students bring laptops to class, thinking that typing their notes will make them better learners than the 'old fashioned' method of writing by hand.

They're wrong.

Taking notes is not about transcribing what is said during lecture. It's about processing the information in a way that helps you pull out what's important and make new connections. Mueller and Oppenheimer (2014) found that the problem with taking notes on a laptop is that we type TOO FAST. Because many of us type almost as fast as a lecturer presents, we write everything down. We shouldn't: it interferes with listening to the lecture, taking in the core message, and deeper processing.

And that's if we stay on task and don't drift onto YouTube during class. (Side note: my students consistently complain that they are distracted by the tech use of students around them. Pulling out your phone or, especially, checking a laptop screen distracts not just you, but students next to and behind you.) Most students who use tech in class report they're distracted by it. If you've ever sat at the back of a classroom and looked at the screens in front of you, you know it's true.

The Advantages of Writing by Hand

One advantage of taking notes by hand is that it slows you down, forcing you to listen more carefully and condense the information to get it down on paper.

Another is that it activates your brain in a different way than typing does. Frank Wilson wrote a fascinating book on hands, in which he argues that brain development is intimately linked to what we do with our hands. Playing with legos and blocks, doing arts and crafts, and spending time in Maker spaces causes us to develop better tools for integrating and processing three dimensional information and problem solving tasks.

But there's more to effective note taking than the question of keyboard v. pen.

Strategies for Notes

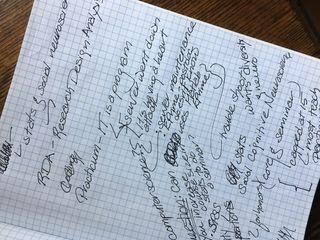

Confession time: I am a 'terrible' notetaker. I say that because my notes are not neat lines of well organized, neatly outlined text. When I leave class, my paper is a scrawled mess of keywords, questions, arrows, and ideas to followup on later (I can prove it — the picture below is one one of my more organized pages.)

Why are they a mess? Because I can't take good notes and listen at the same time. When I sit in a lecture, I give my full attention to the speaker. I ask questions (yes, I'm that student). If I can't ask, I scribble it on my paper. I write down vocabulary and key ideas I know are important that I can look up later. I think a lot about what the speaker is saying and how it relates to other things I already know — either because it compliments it, extends it, or contradicts it. I write that down too. That mess down below? Half my scribbled notes from a one hour meeting.

The key thing about these notes is that this is just the first step. My goal in taking notes during the meeting is not to record what is said. Rather, it is to jog my memory so I can take good notes after the class or meeting.

Immediately after the meeting, I took these scrawled notes and spent five minutes writing a careful summary of what I thought were the main points. They were still fresh in my mind and a glance at that scribbled mess brought key ideas to mind. At the end of that day, I looked at those scribbles and my summary and used them to carefully walk through the meeting in my memory, writing an outline. That outline was not organized temporally, but rather around what I saw to be major themes that came out of the meeting. At the end of my organized summary were sections for additional information: details to follow up on, additional questions to ask, and links to other material I had at hand. Sometimes I type that, sometimes I write by hand.

I follow the same process when taking notes for class.

When pulling together my notes to prepare for an exam, I never read them. What I do is use my notes to put together a NEW set of notes that I've processed even more.

- For a class, I think about the big picture that the professor and textbook have been trying to get across. This can be a great time to re-read the syllabus and the textbook Introduction. Often, it will have laid out the larger set of questions the course is supposed to address. For a set of meetings or a project, I think about the bigger issues we are trying to address.

- I write out a series of questions. This is where tech is AWESOME. It's easy to change. So I write out the major questions the course has been asking — each section and within each section each class. I pull together everything in my notes and in the readings (OMG — I hate to take notes on readings.) I will often have questions written in my notes or in the margins of my readings. I put these in too.

- I answer the questions. This is where integration comes in. Pulling in the information from the textbook and the class and even the homework assignments makes it easier to remember and makes it easy to see connections. That's where those AHA! moments come from.

Why does this work?

- It is very difficult to memorize discrete pieces of information. It is much easier to answer one big 'chunk' of information: a question and an answer.

- Building associations between bits of information activates entire networks, making them easier to remember.

- It is much easier to remember causal chains and arguments than discrete facts.

- IT TAKES A LOT OF TIME AND REQUIRES PROCESSING. Every time I think about the information again and reorganize it, I learn more about the material. I don't study from my notes. Writing notes is studying.

Cornell Notes and Cognitive Maps

For those of you more committed to daily note taking (or more organized) than me, the Cornell Note taking system does something similar in a daily basis. The definitive guide is on their learning center's webpage: The Cornell Note-Taking System. It basically suggests you divide your paper into three sections:

- A large section on the right 2/3 of the page where you take notes on the fly.

- A column on the left third of the page for comments. Here you pull out key vocabulary, make connections, ask questions, and PROCESS. You can do this during or immediately after class.

- The bottom inch or two of each page. Here is where you read your notes and pull out the big points.

You'll notice the similarity between this (and many other note taking systems) and my own disorganized process. PROCESSING IS KEY. Writing it down is only a way of helping your memory work more easily. You then need to consolidate and reconsolidate the memory in multiple forms to make it easier to retrieve.

Concept maps are another way to organize information. They work best when you know the information at hand are are trying to figure out how things fit together. I find them a good way to study or organize a paper. However, I have seen students use them very effectively to learn new information.

How To Study From Notes

One of the classic mistake students make with notetaking is trying to study from their raw notes or raw highlights.

Don't do this.

Take studying from highlights as an example. Students frequently highlight the first time through reading difficult material. It 'saves time' because you don't actually have to write things out. Then when they study, they read through the 'important' highlighted material, skipping the rest Unfortunately, what we think is important on our first read is often NOT what turns out to be the key information when we go back. That's the problem.

It is often more effective to use one of the reading and note-taking strategies suggested here. Read the headers to find out what's important. Read it again to get the big picture. Then STUDY, highlighting and taking notes on key information and processing it.

As described above, I study from my notes by reorganizing and reintegrating the material. In the Cornell System, they suggest you use the columns to test yourself. Read the main body of your notes. Generate many questions, both that you are interested in, and those you think may be on the exam. Write those in your left margin. Now cover up the main information and answer the questions you just wrote down. Every time you're not sure of an answer, look at the main notes to improve your answer and make stronger linkages.

Combining Handwritten Notes With Digital Records

I am a fan of paper notebooks when I'm trying to slow my thinking down (I am a dot person myself). I wrote a fairly detailed description of a paper organizing system that can be expanded to a class note system in A Pretty Good Organizing System For Non-Linear Thinkers.

However, I strongly prefer my final notes in digital form. As I said earlier, outlining works well digitally because it is flexible and can be changed. As described above, I often go from garbled notes to a long typed outline. When I'm done, I throw the notes I took on the fly out because everything useful in them is integrated into other forms. But there are other options.

In my opinion, the best way to use the Cornell system is to combine digital and text. And that's where tech really shines.

Take your notes. Photograph them with your cell phone. Then stick them straight into a digital notebook. I am a Microsoft OneNote fan (free app download for your phone, and it works on your Windows or Mac laptop or tablet). Other people use Evernote. You can use Word or Google Docs or anything that allows you to drop an image into a page and combine it with text.

You can essentially take the Cornell Note System and move it in the digital age. Create a two column table. Drop the photo of your notes into the large right column. Now type all your questions and notes on your left. You can add text boxes to put in your summaries as needed.

This system has several advantages:

- It makes all your notes always available to you on phone, tablet, computer, and web.

- You can use digital highlighters, pens, and tags. Most systems will do handwriting recognition if you want. (Hints on improving your handwriting so a computer can read it are here.)

- You can photograph or scan parts of your readings and integrate them with your notes for supporting information.

- IT IS INFINITELY EXPANDABLE. If you're really working your Cornell notes, you can write a LOT of questions and pick in a LOT of vocabulary. A digital notepad can adjust the size of the column and page to fit your needs. You don't have to adjust to it.

Different Folks, Different Strokes

Just as there are many different ways to learn, there are many different ways of taking notes. Start searching online and you'll find dozens. No one taught me the weird system I use — it just developed over time. This is just a start. The key is, find a method that works for you. That can be digital — if you think with your laptop and don't act as a stenographer. It can listening and writing down information later. It can be writing by hand because the physical act of writing helps you retain and process information.

But what NOT to do is to have words go in your ears and out your fingers onto a page. Note taking is effective when you think about what you're writing. The written record of that thinking is just a tool.