Persuasion

The Three "Laws" of Human Behavior

Framing human behavior in terms of investment, influence, and justification.

Posted October 21, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- The unified theory of psychology frames human behavior in terms of three factors: investment, influence, and justification.

- Investment frames animal behavior patterns in terms of work effort that emerges because of evolution and learning.

- Influence refers to how different individuals impact each other and relate in competitive and cooperative ways across systems.

- Justification refers to how human persons organize and legitimize their activity based on networks of propositions.

What is the best way to frame human behavior? According to the unified theory of psychology1, we can think of human beings as: (a) animals engaged in “behavioral investments” who are also (b) primates engaged in social influence in a relational matrix who are also (c) persons engaged in justifications in a sociocultural context.

To see these three vectors, consider a lawyer engaged in the defense of her client. First, we can track the lawyer’s behavioral investments. We can track these in terms of both what the lawyer is doing and in terms of the neurocognitive processes associated with those actions. Things like walking, getting dressed, eating, and going to the bathroom are all “basic” behavioral investment patterns. We can frame such actions in terms of goal-directed activity, where the individual is moving from the current state to the desired state. This is the “path” of behavioral investment. Using the excellent work of cognitive scientist John Vervaeke and his colleagues, we can frame the neurocognitive processes associated with choosing such a path via what Vervaeke calls “recursive relevance realization.” Put in common language, this means that the individual is scanning the environment for what is relevant to realize her goals and that there is a constant, recursive pattern that is modeling both this process and other potentially relevant goals, pathways, risks, or constraints.

Ultimately, according to the unified theory of psychology, we can frame the principles that make up the “law” of behavioral investment in terms of (a) energy economics; (b) evolution; (c) behavioral genetics; (d) neurocomputational control in the organism; (e) learning; and (f) developmental life history. To give just one example of how we can apply these principles to the behavior of the lawyer, we posit that when the lawyer parks her car outside the courthouse, she will intuitively take the “path of least effort” to get to the courtroom. This is an example of the principle of energy economics at play.

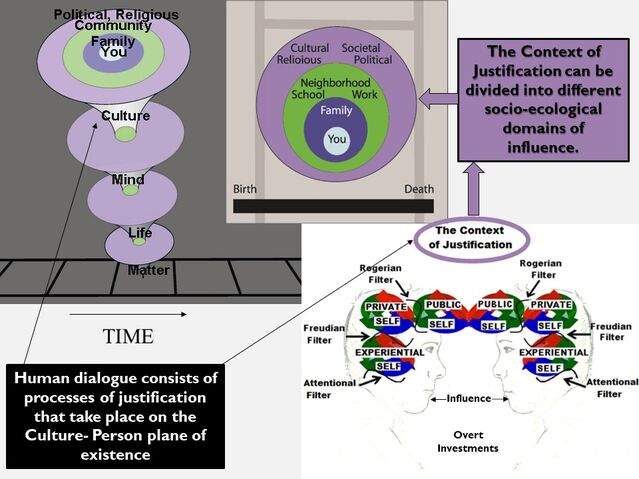

The social and relational matrix consists of the way human behavior investments and values affect their relational world. Regarding the lawyer, we can place her in a socio-ecological network of relations that started even prior to her being born. For example, we can wonder whether her parents embraced her mother’s pregnancy or not. The fact that she may have been named well before her birth points to the primacy of this relational network—it exists even prior to the specific human being. We can then place her in nested “spheres of influence and ecology,” such that we can see the kinds of relationships she had over time with her: (a) family of origin; (b) peers and friends; (c) romantic partners, and (d) groups. We can then nest those relational dynamics in the larger community and professional contexts, and then even larger cultural contexts, such as the fact that she lives in the United States and identifies as a Christian.

The primate world of social influence can be first framed in terms of the way in which an individual’s actions influence the behavior investments of other individuals. However, in social primates like humans, evolution has prepared us with a rich relationship system that frames our motivations and emotions in the relational world. According to the unified theory, we can frame this “law of influence” by the way we track our level of social influence and relational value and examine how that reverberates in the social sphere. Social influence refers to the extent that we can influence others according to our interests, and relational value refers to the extent to which we are known and valued by important others. In addition, our relational system tracks the way we relate to others on the dimensions of “competitive power” framed by the relational poles of dominance and submission, “cooperative love” framed by the relational poles of affiliation and hostility, and “freedom and engagement” framed by the relational poles of autonomy and dependence.

Applied to the lawyer, she is trying to influence her client, the judge, and the jury to act in a way that results in an acquittal. These are the instrumental aspects of influence. Of course, we can also explore how she felt in terms of relational value, and we can examine the processes of competitive power, cooperative love, and freedom versus dependency.

Other animals invest and influence each other in systematic ways, but only humans engage in the third law, which is justification. Processes of justification emerge with propositional language, and humans are the only known animal that builds justification systems. These are systems of knowledge that humans construct to determine what is the case and what ought to be the case.

The laws that humans develop are great examples of systems of justification. Indeed, these are the formalized systems of justification that connect the rules of society to the institutionalized power structures, such as a police force and the corrections system. This highlights that, in addition to systems of justification, humans have also evolved our technologies in a manner that is radically different than other animals. Together, justification systems and technological evolution make human societies unique compared to other animals.

The lawyer is someone who operates on the culture-person plane of existence. She lives in a context of justification that ties together the relational world (see diagram below). Broadly defined, justification processes are ubiquitous, as they structure the implicit rules of conversation, rhetoric, and action. Of course, as a lawyer, she is engaged in the explicit process of justification as her job. A lawyer can be described as a professional justifier. Her job is to know the history and processes of formal, legal justification procedures that channel people into categories like “guilty” and legitimize sanctions, going all the way to putting someone to death in some cases. Here we see the “law” of justification as literally framing the laws of human behavior and the behavior of lawyers.

The bottom line is that investment, influence, and justification are powerful ways to describe and explain human behavior. Indeed, they are so powerful that they might constitute “laws,” at least in a general dynamic sense of being up to the task to frame the complexities of human activity.

References

1. Henriques, G. R. (2011). A new unified theory of psychology. Springer.