Anger

Adaptive and Maladpative Anger

Additional reflections on the anger-aggression distinction.

Posted January 21, 2015 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Steven Laurent replied to my post on the importance of differentiating anger and aggression and offered some useful points of clarification. I agree with him that we are not very far apart overall and that we should avoid coming across as unnecessarily polarized. As such, let's start with some points of agreement.

First, we agree that anger and aggression can be conceptually distinguished, and I agree with him that it can be a fuzzy boundary. Second, it seems we agree that aggression is a primary problem, and that it often (although not always) stems from anger. It follows from this we should often work to reduce anger. Third, many people are angry in maladaptive ways and we need strategies to reduce this anger (we are both clinicians who work with some clients who have "anger problems"). Fourth, anger can be problematic because it can be cyclical, it feeds back on itself via hostile interpersonal exchanges, thus making it particularly likely to be maladaptive. Fifth, Steven acknowledges that he has some exceptions to his "zero anger" goal. Six, we both agree that, by and large, the world would be a better place if folks were less angry.

Given all this agreement, where is the difference? The basic difference is that I see angry feelings as being adaptive or maladaptive depending on context and how they are expressed.

How we frame anger

The difference in opinion can be well-characterized by our reading of a famous quote from Aristotle, which Steven explicitly references in another post:

Anybody can become angry, that is easy; but to be angry with the right person, and to the right degree, and at the right time, and for the right purpose, and in the right way—that is not within everybody's power; that is not easy.

—Nicomachean Ethics, 1109a25

In contrast to Steven, I basically agree with this quote and explain why here. The difference, which I see as important but not major, is in how we frame what anger is. My basic position is that angry feelings per se should not be thought of as "bad" any more than sadness or frustration or anxiety should be thought of as bad. All basic emotions can be adaptive or maladaptive. Negative emotions are maladaptive if they are under-regulated, chronically accessible, have low thresholds, and lead to problematic behaviors that increase suffering and impairment. Thus, my preferred frame is differentiating adaptive from maladaptive anger, which is how I read the essence of Aristotle's quote.

My perspective stems in part from my concern that many of the "negative emotions" are viewed as "bad" in an unhelpful way (e.g., Feel depressed or anxious? You likely have a brain disease and need a pill).

Socio-emotional processing

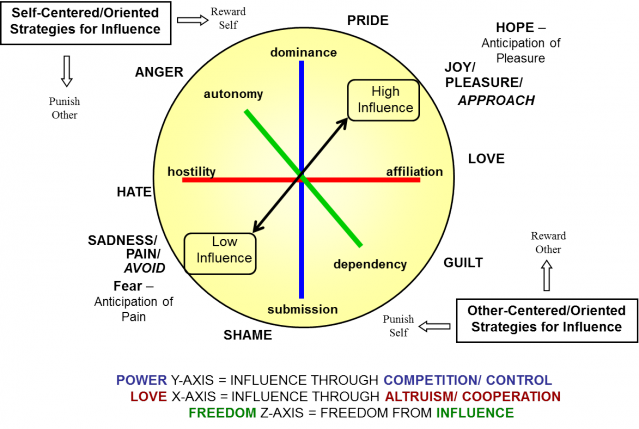

It also stems from my view of socio-emotional processing. My position is that humans have a basic, evolved, socio-emotional architecture which allows for the quick processing of social goals and emotional responses. I developed a map of this processing called the Influence Matrix. From this angle, the core, immediate experience of anger is important because it is tied to one's self-interest. Guilt is important for the opposite reason—it signal's one to orient to another's interest.

My perspective is that, although they can be maladaptive, both anger and guilt (and pride and even shame) can be adaptive because they serve as important guides for one's self-conscious system to use in decision making in the relational context. I also am worried about labeling angry feelings a problem because I think folks are often alienated from their "true" feelings. And, as Steven talks about in his post, I do see people who "stuff" their anger in problematic ways. These are the reasons I take some issue with Steven's framing of anger always or even almost always being a problem.

That said, however, my guess is that both Steven and I have a very similar idea of what constitutes mature and healthy psychological functioning. For instance, if someone cuts in front of me in a line, I will feel a flash of anger. From my perspective, that is "by design" and an adaptive thing to experience.

Now, however, what happens with that flash is what defines whether it remains adaptive. If I haul off and impulsively hit the guy, yell at him, or stomp off complaining that everyone in the world is selfish, these are all immature, impulsive, maladaptive responses.

From my perspective, the flash of anger alerts me to the fact that my interests have been violated. However, I then need to effectively engage my self-conscious, justifying mind as to what to do about it. That is, when I think it through, considering the situation, my identity, my goals and values, I need to answer some important questions: Does it really matter in this case? Maybe the guy is in a real hurry? Maybe I could check in with him and let him know I was a bit concerned? Maybe I should just forget about it? and so on. I would generally react to such a situation with little, if any overt anger, and if I engaged the individual at all, it would be with a calm, questioning attitude, rather than an aggressive, combative one.

My perspective is that the anger flash orients me and that is not a problem, per se. What is a problem is when folks jump from the flash to extreme interpretations and aggressive actions, unnecessary fueling the flash into a fire that creates far more problems than it solves.

My guess is that Steven would see my overt behavior as the kind of behavior he is striving to get folks to engage in. Thus, at the overt behavior level, Steven and I are advocating for very similar ways of being. I also think we have probably have slightly different things in mind when we use the term "angry feelings." I often have just the "flash" and labeling of it in mind, where he as the building of it into hostile thoughts and aggressive actions. In short, there are lots of similarities in our views, and probably most of the differences are found in semantics and perhaps minor theoretical differences about how the human mind works.