Gender

Why Are Women Paid Less Than Men?

We go to the ends of the earth to investigate the cause of the earnings gap.

Posted October 14, 2013

In January 2005, Larry Summers, then president of Harvard University, offered a lunchtime address to participants at the Conference on Diversifying the Science & Engineering Workforce. Introducing his talk as an “attempt at provocation,” he proceeded to lob a heavy grenade into the ancient war of the sexes. Specifically, he wondered aloud whether an innate, gender-related difference in aptitude between men and women was the culprit behind the huge gender disparity observed among hard-core scientists.

What can the Khasi teach us about the gender gap?

Citing research showing that women make up just 20 percent of U.S. professors in science and engineering, Summers questioned whether, “in the special case of science and engineering, there are issues of intrinsic aptitude, and particularly of the variability of aptitude, and that those considerations are reinforced by what are in fact lesser factors involving socialization and continuing discrimination.” In other words, he wondered whether women might be at an inherent intellectual disadvantage when it comes to getting to the top in the hard sciences.

The reaction against Summers’ comment was swift, huge, and harsh. A top biologist from MIT, Nancy Hopkins, exited the room in a huff. “For him to say that ‘aptitude’ is the second most important reason that women don’t get to the top when he leads an institution that is fifty percent women students – that’s profoundly disturbing to me,” Hopkins told reporters. “He shouldn’t admit women to Harvard if he’s going to announce when they come that, hey, we don’t feel that you can make it to the top.” The local and national media went wild, and a campaign quickly ensued to fire Summers. The following year, he resigned his post at Harvard—partly because of the reactions to his comments at the conference.

Summers’ comments – viewed as sexist at worst, tone-deaf at best, and utterly politically incorrect (and he apologized for them several times) – at least did fit with eons of tradition. For millennia, culture and science have colluded to explain why women aren’t as competitive and ambitious as men. In the book of Genesis, Adam’s role was to be Eve’s master. In ancient Rome, women were citizens, but they could not vote or hold public office. Many religions, laws and cultures around the world persist in subjugating women and forbidding them from competing in a man’s world.

Summers’ comments also bore the stamp of Charles Darwin, who more than 150 years ago proposed that successful males evolve to win the mating race. Since then, Darwin’s theory of natural selection helped to explain why males are generally more aggressive and violent than females. After all, men had to go out and compete with men from other tribes to kill animals, while women raised and nurtured the young.

If evolution is responsible for a comparative lack of competitiveness in women, a few hundred years of cultural changes would not make a difference. Evolution could help explain why the number of women in high-profile jobs still pales in comparison to that of their male counterparts, or why U.S. women still only earn, on average, 80 cents for every dollar earned by a man.

After citing the research and mentioning his “innate differences” hypothesis, Summers explicitly told his audience: “I’d like to be proven wrong on this one.”

In our new book, The Why Axis: Hidden Motives and the Undiscovered Economics of Everyday Life, we detail our adventures into the invaluable WHYs we face as a society, including this one: why do women earn less than men?

In particular, we test what part of the gender gap in labor markets is due to culture. We can’t just take for granted, in the absence of data, that women were innately less able than men. We decided to start collecting evidence by looking at ordinary men and women in their natural habitats and doing things people do every day—say, participating in a gym class or answering job ads on Craigslist—and we used the full gamut of experimental tools at our disposal to answer these questions: To what degree are the differences between men and women (such as levels of aggression, competitive drive, and wage-earning power) truly innate? To what degree are they culturally learned? In the end, we’ve come up with a unique explanation for the persistent differences we observe between men and women, particularly when it comes to competition.

Let me paint the picture for you. The sign on the road leading to the city of Shilong in the Khasi hills of northeast India had a puzzling message: “Equitable distribution of self-acquired property rights.” Later we’d find out that the sign was part of a nascent men’s movement, as the men in the Khasi society were not allowed to own property. We’d traveled across the world in search of such a parallel universe—one where men felt like, “breeding bulls and babysitters”—because evidence in the U.S. was starting to point to a massive gap in preferences towards competition between the genders and we wanted to understand the reason why.

Our plan was to take a simple game to a matrilineal society (the Khasi) and patrilineal society (the Masai in Tanzania) and give participants just one choice: Earn a small certain payment for their performance in the game or earn a much bigger payment for their performance, but only if they also bested a randomly chosen competitor. The game we settled on? Tossing tennis balls into a bucket 3 meters away. The experiment was conducted with Kenneth Leonard as a coauthor.

First, though, we headed to the plains below Kilimanjaro, the tallest mountain in Africa, where the proud Masai tribesman lived. The Masai, dressed in brightly colored robes and carrying their spears, follow the calling of their cattle-hearing ancestors. The more cattle a man has there, the more wealth he possesses. A man’s cows are more important to a Masai man than his wives and a cattle-wealthy Masai man can have as many as ten wives.

Khasi participating in competition experiment.

When we pulled up to the Masai village armed with cans of tennis balls, small toy buckets, and lots of money we found the villagers waiting for us. We told those that wanted to participate that they had the option of earning $1.50 (a full day’s earnings, there) each time they successfully tossed the ball in the bucket after 10 tries versus $4.50 for each successful toss if they beat their randomly selected opponent.

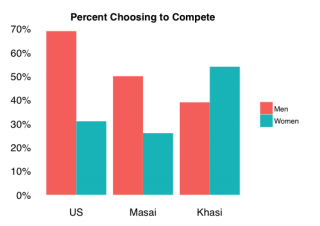

What did we find? The Masai women had little interest in competing, with only 26% choosing that option. The Masai men? 50% chose the competitive option. This was in line with rates in the U.S. (Before we went to Tanzania we ran a similar experiment and found that 69% of men wanted to compete versus just 30% of women.)

Women compete more in the matrilineal Khasi tribe

When we went to India and had the Khasi play the exact same ball-and-bucket game we found that the Khasi women were just like men in the Masai: 54% of women wanted to compete versus 39% of men. The results, summarized in the figure, showed that culture was capable of turning the world on its head, gender-wise. In fact, the Khasi women were more competitive than the Masai men. Indeed, the Khasi women were like US men, and the Khasi men were like US women!

Our study suggests that given the right culture, women are as competitively inclined as men, and even more so in many situations. Competitiveness, then is not only set by evolutionary forces that dictate that men are naturally more inclined than women (nature). The average woman will compete more than the average man if the right cultural incentives are in place (nurture).