Relationships

Recovering From Disorganized Love

A path to heal the turmoil of simultaneously craving love and running from it.

Posted June 8, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Disorganized romantic love is characterized by a vacillation between anxious and avoidant behaviors.

- Disorganized love can stem from complex posttraumatic stress disorder (c-PTSD) in childhood.

- Disorganized love can be overcome with tools to rebuild a secure base of self-love.

I have a broken heart. But I’m not sure I have ever been in love.

These conflicting realities can arise when we crave love and run from it. Those who study adult attachment call this “disorganized attachment style," and it's characterized by a vacillation between anxious and avoidant attachment.1 In other words, chasing or running, which can change within and between partnerships. The universal characteristic is fear.

Because romantic attachment evolved as an extension of the attachment system activated in childhood, how our parents treated us can become what we are attracted to in a romantic partner. Mistaking fear for love is cultivated by a parent–child attachment bond in which a parental figure’s attention was inconsistent, shaming, and sometimes frightening.2

Disorganized love in adulthood is best summed up by the famous line from Groucho Marx: “I refuse to join any club that would have me for a member.” Translation: “Because my value and self-worth are questionable, anyone who would have me is also no good.” Put into action, this looks like pushing away from those who love us, especially when a relationship becomes stable and secure.

The handful of times I thought I was “in love,” the man communicated that he did not want a relationship before we even started dating. Most recently, the line was, “I’m not sure I love myself enough to love someone else.” A red flag. Yet, for me, it was like the green flag at Talladega.

My brain is programmed to seek elusive love like an addict seeks the next high. It is a pleasure elixir like no other. Each relationship that “felt” like love to me moved fast—and was full of passion. Then, there would be a subtle shift in the man’s behavior, detectable to no one except me. Fear would take over, masquerading as anxious excitement. I chased harder.

Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

This behavior is part of a constellation of symptoms that stem from complex posttraumatic stress disorder. C-PTSD can develop from intermittent shaming and neglect in childhood.3 A series of small negative interactions that add up to a major trauma. When parental behavior is unpredictable, children turn into master energy readers on high alert for subtle shifts in others’ behavior so that they can adjust their own.

By age 5, the hardware in my brain was programmed to equate chasing with love. If love is available to me, my avoidant style kicks in: I’m in the wrong club. Stable love triggers a feeling of being “with the wrong person” because my core belief is that I am not worthy of love.

A capricious man with one foot out the door, on the other hand, sparks desire. My anxious style kicks in. Just like when I was a child, I think, “They do not love me, I need to try harder. My persistence will make them notice and love me back.”

Why does our parental relationship come to bear on our romantic relationships? Although it seems like a major design flaw, evolution by natural selection seeks the path of least resistance when there is pressure to adapt to a new problem. When humans evolved larger brains, evolution selected for the birth of small, underdeveloped babies with a long developmental period outside the womb. To keep fragile babies alive, romantic pair-bonds evolved so two nonrelated adults bonded for an extended period to raise a helpless baby. Evolution then co-opted the parent-child attachment system and jerry-rigged it so that the greatest hits of your parent-child attachment play during adult relationships, too.

C-PTSD and disordered attachment are common today because modern parenting has been characterized by trauma-inducing tactics, such as parent-child separation, shaming, and punishment.4 Add to this the reality that there is (1) less dependency on romantic pair bonds to raise children and run a household and (2) infinitely more fish in the sea thanks to social media, and you have modern romantic relationships that are more fragile than ever.5

The good news is that there is a workaround: You must become the parent you never had.

The process is straightforward, but not as simple as it seems. After my divorce, I spent four years reconnecting to my authentic self through therapy, introspection, and building a life that I truly loved. I thought I was in a good place to get into another relationship.

When I met the man who raised the red flag, my self-love went out the window. This is because romantic relationships are the strongest trigger of our core childhood wounds. When I noticed that my partner’s “love” speed had fallen from hyperdrive to a slow trot, I took what remained of my cup of self-love and poured it all onto him. (I even wrote him a love story that I’ve since rewritten as a story about loving yourself; linked below).

The relationship ended as fast as it had begun. The original factory setting inside me still read, “I am no good” and when triggered by this relationship, it subsumed my entire life.

We cannot have fulfilling, loving, stable relationships if we do not short-circuit the programming that leads some of us to close our hearts to those who love us and chase the elusive hearts of those who are not available to us. The panacea for disorganized love is working every day to cover the hardwired program called “I’m not lovable” with 56,000 pounds of fully leaded self-love.

6 Steps to Recover From Disorganized Love

Here are six initial steps to becoming the love of your own life:

1. Gain awareness. This can be as simple as a journaling exercise broken down into two parts.

- Recall three early memories from your childhood. Our earliest memories give us some insight into how our parents treated us. My earliest memory is being yelled at and spanked for eating cookie dough. I don’t remember how I felt in the moment, but it gave me a clue that there was shame involved in my early life that is showing up in my adult relationships.

- Recall your feelings and behavior in past relationships. Did you change anything about who you are as a person within the relationship? If yes, you have an old, and faulty, behavioral program playing out in your adult relationships.

2. Repair. This will mean doing things every day to love and protect yourself even when it doesn’t feel good or right. There are many resources available to help build self-awareness and self-love; you could, for example, download my self-love book here and write a love story for yourself.

3. Make a love map. Recall your previous partners and write down what you liked and did not like about each. Pay close attention to the partners who broke your heart. From that list, build your ideal partner. What are your must-haves and what are the warning signs to look out for that indicate a dealbreaker? If you are like me, inconsistency will trigger interest, but it is a red flag. It is your emotional pain from childhood being drawn to a person with a similar childhood wound. In these moments try doing the opposite of what you initially would like to do.

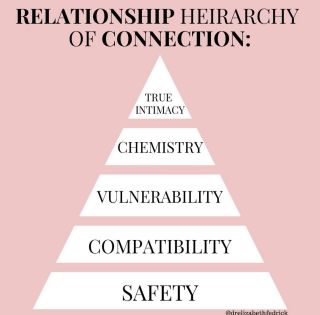

4. Follow the hierarchy of connection. First, you must feel safe. The connection must also build slowly, not at lightning speed. (See the chart at left, from Elizabeth Fedrick.)

5. How do you know when a relationship is safe? Set a boundary or make a direct request for something in the relationship. See how your partner responds and if their response is consistent over time. Do they respect the boundary (e.g., ending a call by 10 p.m. so you can get to bed on time) or honor a request that you make (e.g., spending 10 minutes together in the morning before going to work)?

Also ask yourself: How does your body feel? If your body feels one way when you are with your partner (nervous or anxious) and your head feels another way (safe), your head is likely lying, and your body is telling the truth.

6. You have a safe relationship. So, what now? Boredom may set in when a relationship becomes safe and the urge to run may bubble up. Security within a relationship is a beautiful gift and being comfortable in a relationship that is safe is possible only if you have recognized and tended to your childhood wound of low self-worth.

With hope for the future, I’m in repair.

References

1. Paetzold, R. L., Rholes, W. S., & Kohn, J. L. (2015). Disorganized attachment in adulthood: Theory, measurement, and implications for romantic relationships. Review of General Psychology, 19(2), 146–156.

2. Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the Preschool Years: Theory, Research, and Intervention (pp. 121– 160). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

3. Resick, P. A., Bovin, M. J., Calloway, A. L., Dick, A. M., King, M. W., Mitchell, K. S., ... & Wolf, E. J. (2012). A critical evaluation of the complex PTSD literature: Implications for DSM‐5. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(3), 241–251.

4. Jensen, S. K., Sezibera, V., Murray, S. M., Brennan, R. T., & Betancourt, T. S. (2021). Intergenerational impacts of trauma and hardship through parenting. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(8), 989–999.

5. Parker, G., Durante, K. M., Hill, S. E., & Haselton, M. G. (2022). Why women choose divorce: An evolutionary perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 300–306.