Throughout the history of warfare, service members have been placed in unimaginable situations, often situations in which they have to make difficult decisions. Frequently, decisions made during deployment have lifelong consequences. Many veterans have expressed a desire to be the person they were before they experienced trauma, and they often try to suppress or avoid memories of the trauma they have lived through. However, the use of avoidant coping strategies has been found to be counterproductive in the long run. By attempting to avoid the traumatic events service members have experienced, they end up exacerbating the intensity and frequency of their trauma memories and the sequelae and symptoms of those memories over time.

Some veterans are able to move past trauma with minimal dysfunction in their lives; however, for others, the traumatic event creates havoc and chaos. Trauma symptoms can become so problematic that they result in family discord, divorce, social dysfunction, significant substance use, employment difficulty, physical health difficulties, legal problems, and more. And the disruption of service members’ lives as a result of trauma symptoms is hardly uncommon. Due to the dysfunction and negative impact of trauma and its symptoms in the lives of service members, the VA has recognized and developed the VA disability rating system. The disability rating system considers both physical and mental health-related conditions. The more areas of a veteran’s life that are impacted (i.e. social and occupational difficulty or physical limitation and/or pain), the more financial compensation that veteran potentially could be warranted. I am a firm believer that veterans are entitled to every dollar that they are afforded and then some...Many can argue that the lifelong implications and symptoms that veterans have to endure cannot be quantified or compensated with a dollar amount. The VA does its best to equitably compensate veterans based on their level of dysfunction. However, if the veteran could eliminate the disabling experience that initiated their impairing symptoms, it is possible that they could exceed the amount of their VA compensation by functioning optimally in the civilian sector. Essentially, they would be able to have a greater positive economic impact and earn a higher living wage if they did not experience disabling symptoms. Given the high level of training military members receive, the values, discipline, and structure instilled by military training and service often lead most veterans to make dependable, hard-working, and effective employees.

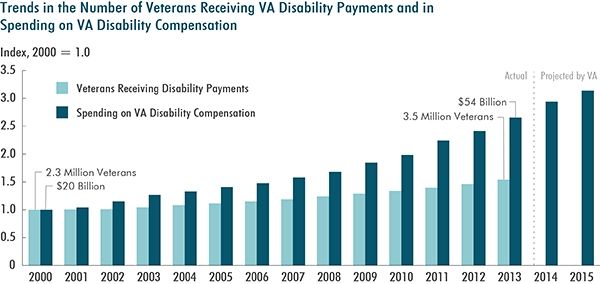

According to the VA Disability Rating System, in the year 2000, the average compensation provided to veterans through the disability rating system was about $20 billion for 2.3 million veterans. In 2013, that number rose to 3.5 million veterans receiving $54 billion in compensation. This number has continued to rise over the last several years and will hopefully continue to do so, enabling veterans to receive the compensation they deserve. A major reason for the spike in veterans receiving compensation is the continued 14-year wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. When service members are sent to war and later return home, there are often significant consequences to service—economics being one of them. Unfortunately, many veterans who are still in need of services and compensation for VA benefits have not taken advantage of the services offered. Many factors impact veterans’ decisions not to seek care— a main one being stigma. Two examples of stigma are: one, a veterans’ hesitation to seek mental health services due to being perceived as “weak” or “vulnerable;” and, two, the possibility of having negative career or job implications as the result of potentially impairing symptoms. As I have said in a previous blog, it takes a nation to build a military and go to war. And, it takes a nation to welcome them home. Compensating our veterans for their service is the first of many steps that should be afforded to veterans for their sacrifice. If we send people to war, it is a fundamental imperative that we take care of them when they come home. The tide is changing, and the VA has gone to great lengths to decrease wait times for compensation and pension evaluations so that veterans are streamlined through the process. There is no perfect system, and the pendulum has and is continuing to shift in the right direction so that our brothers and sisters in arms are taken care of.

To specify the rating system with an example, if a veteran diagnosed with PTSD has a 50 percent service-connected disability rating and they have a spouse and one child, they would receive $978.64 each month. Yearly, that is roughly $11,745. The pay for a veteran that is 100 percent serviced-connected increases significantly. They would approximately $3200 monthly. Although this money is not taxed, many veterans still struggle to make ends meet. Anecdotally, there is a misconception that if a veteran receives a 100 percent service connection, they will be able to live a “lavish” lifestyle. That is simply not true. This money can definitely help decrease financial distress, however, many veterans still struggle to pay for things they and their families need.

Once a veteran receives a disability rating and compensation is provided, there can be fear that the disability rating might be decreased or taken away if the VA finds evidence the veteran’s symptoms have improved to a more manageable level. Once veterans receive a service-connected percentage of disability, it is not a fixed rate for life—although it could be. The VA has the right to decrease the compensation rate if the veteran shows material improvement in their ability to function in daily life whether that be in relation to a physical or mental health-related condition. According to the Department of Veteran’s Affairs Service Connected Disability website (2017), if a veteran has less than a 100 percent disability rating, has been receiving compensation for less than five years, and has shown medical and social improvement, the VA can reduce the percentage of disability and compensation based on the evidence found. However, if a veteran has been receiving benefits for longer than 20 years, it is considered a continuous rating and the VA cannot lawfully reduce the rating. At 10 years, a veteran’s rating cannot be terminated, but it can be reduced. If a veteran’s disability rating is reduced, a veteran has the option of requesting a reexamination, and they should contact a Veterans’ Service Organization representative to advocate on their behalf.

The VA provides great and well-needed services, and they save lives every day. Unfortunately, some veterans walk away from the VA dissatisfied and displeased. There is no perfect mental health and medical system, and the disability rating scale is not perfect either. There is no one program that provides a “fix all” solution. What it will take is public and private partnerships moving forward in order to maximize reach and expand access, frequency, and quality of care.

Many veterans who receive benefits fear their benefits may be taken away at any point in time. Unfortunately, this fear of disability ratings potentially being lowered if there is substantial evidence that the veteran has made improvement deters people from seeking and fully engaging in well-needed treatment. For instance, if a service-connected veteran engages in an evidenced-based trauma-focused treatment for PTSD that has been shown to reduce symptoms upon full completion, and as a result of that treatment their overall dysfunction decreases, that veteran could be at risk of decreased disability ratings if that improvement is documented and gathered during a medical evaluation. Veterans who know the disability rating system may be deterred from seeking care at the VA because of that potential. The more dysfunction one has, the more money they receive; so increased symptomology is incentivized and reinforced. If veterans struggle with employment and optimal functioning, it makes sense that those veterans may not want to show improvement. This is one lens to look through.

Unfortunately, there is no perfect solution to this problem. However, there has been plenty of debate about possible solutions. One solution discussed would be to extend the time period between the rating system from the initial evaluation and reevaluation. This solution could assist with decreasing stigma and reducing the fear of losing a percentage rating with the potential benefit of encouraging people to fully engage in well-needed treatment. This would allow veterans to seek a high standard of care, receive benefits, and practice their skill-sets learned with a longer time to adjust for life stressors that may continue to exacerbate symptoms. If there is no reoccurrence of symptoms, then one may experience a reduction in compensation. If there continues to be notable impairment, then the percentage of disability rating could stay the same or increase. Another potential solution is to continue the private-public partnership so that veterans can receive care outside of the VA. If veterans fear that making progress would jeopardize their disability rating when seeking care at the VA, those concerns are potentially lessened with treatment in the private sector. These issues about disability ratings and improvement in functioning are only a few of the many issues debated in the current veterans’ issues climate. Although they are hotly debated, the pendulum is moving in the right direction by placing our veterans first.

References

VA Disability Rating System. 2017. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC. Available online at http://www.va.gov/compensation/rates-index.asp