Media

Rooting for Two Characters to “Just Get Together Already”?

Why are fans so emotionally invested in their favorite couples?

Updated September 19, 2023 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- Fans often have a strong emotional investment in seeing their favorite fictional characters become a couple.

- Known as "shipping," this is connected to identification and can be a way to explore relationship dynamics.

- Shipping may also relate to "love maps"—what we like, who we like, and how we like our relationships to be.

Have you ever watched a movie or a series and found yourself rooting for two characters to become a couple? Maybe said to yourself, “Look at the sparks flying between those two” or made a social media post with the two characters and heart eyes emojis?

If you have, you’ve engaged in “shipping,” a common practice among fans. The term comes from “shipper”, short for "relationshipper"—as in, “I ship those two together so hard.” While the practice has been going on for decades, the term went mainstream with two characters in the 90s who captured the collective fascination of many fans: Fox Mulder and Dana Scully of The X Files.

It’s the 30th anniversary of that popular series, which has brought shipping back into the cultural conversation. It’s a practice that is both common and controversial, and the source of some surprisingly passionate disagreements among fans.

Do You Ship It?

Shipping brings with it a strong emotional investment in seeing one’s chosen romantic pairing (sometimes called the “OTP” or one true pairing) portrayed as such on screen. So when fans disagree about who should be paired with whom (and who should absolutely not), there can be strong disagreements too.

Some fans are adamant about their favorite “ships” happening in the canon or onscreen story, while other fans express their desire to see their favorite pairings by writing them into fanfiction, which can satisfy at least some of that longing.

Fans have argued about shipping for decades, famously since some imagined a romantic relationship between Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock in the original Star Trek series. While some fans are shippers, others are not.

Depictions of serious platonic relationships are rare in media, so when there are characters who share a deep platonic love, some fans value that more than making the relationship a romantic one. When shipping pairs up two real people (as opposed to fictional characters), the practice is even more controversial.

Known as RPF (“real person fiction”) when it’s written into fanfic, some fans feel like it’s an invasion of privacy to speculate about celebrities’ personal lives, while others point out that the fan doesn’t actually know the real people and is essentially writing about a character anyway. Bennifer, anyone?

Will They Or Won't They?

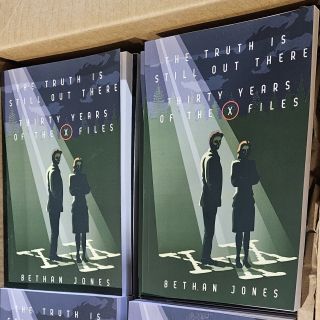

What is it about two characters like Mulder and Scully that inspire shipping? I asked an expert, researcher Bethan Jones, author of the newly released book, The Truth Is Still Out There: Thirty Years of The X Files.

Jones: They just play off each other really really well, that chemistry is a huge part of it. And they’ve got that gender switch with Scully being the scientist, the more rational one, and Mulder being the emotional, intuitive one. This was quite different than a lot of television at that time, this strong intelligent female character and a male character in touch with his own emotions, and that’s really appealing…And they love each other, you can tell just from the way that they look at each other, and that depth of feeling plays a huge role.

Jones says she was not a shipper, but instead part of the “Noromo” (no romance) portion of the fandom, who never wanted to see the characters get together and ruin all that unresolved sexual tension. (The two factions, Jones confirms, slogged it out on early 90s message boards and later the social media platform LiveJournal).

Why Do We Care So Much?

So what is behind the intense investment in relationships between either fictional characters or between celebrities who are strangers to the fan anyway?

Jones: I think sometimes it’s just about that happy ending. And for a lot of people, a happy ending is having your characters fall in love and get together. There’s that sense that they were made for each other, that you can’t have one without the other. And for the most part, they do belong together, and for some people that means a romantic relationship. I think we’re conditioned that way, that romantic relationships equal happiness.

Fans often talk about shipping as something that just happens instead of any sort of logical choice. Characters that barely interact onscreen sometimes become shipping favorites.

Research suggests that shipping doesn’t necessarily involve romantic attraction to the characters, but rather is more strongly connected to identification. Shipping can be a way to explore relationship dynamics that the person is interested in or finds desirable. It can be a healthy process to explore the sense of self.

Shipping may also be related to the idea of “love maps”—an internal map of what we like, who we like, and how we like our relationships to be. These maps guide our sexual and romantic interests.

Popularized by John Gottman as important for couples to understand each other’s lovemaps, people are also motivated to seek out depictions of our individual lovemaps in media. When we find a depiction, that allows a pleasurable escape from stress that can be satisfying. On the other hand, not being able to find one’s preferred lovemaps in media can be frustrating, leading to fans pushing for their ships to be portrayed onscreen—and contributing to “ship wars” when other fans are rooting for a different depiction.

Being confronted with depictions of lovemaps that do not align with an individual’s preferences, on the other hand, can cause anxiety or discomfort, which increases animosity toward fans who are cheerleading for that one.

There has been attempted censorship of fans’ creative works on sites like Archive Of Our Own, in contrast to the fandom mantra of “don’t like, don’t read.” (Most fanfiction sites use filters so readers don't have to stumble over things they don't want to see.)

Shape Your Own Fan Experience

“Don’t like, don’t read” is not bad advice for fans who are passionate about shows and characters. While being passionate is part of the fun of fandom, try to keep some perspective.

Curate your own experience by deciding what you want to read, what you want to watch, and who you want to associate with in fandom—find your people and celebrate what you love with them, whether that’s gushing about how X is perfect for Y, or X is perfect for Z, or X and their best friend are just that. There’s probably someone else who ships the same thing you do (or, like you, avoids shipping altogether).

All of us tend to root for love—of all kinds—because we crave connection for ourselves. Jones sums it up in a way that will resonate with most fans.

Jones: There’s also just finding that joy in living through fictional characters’ experiences. Because as a fan, we do connect deeply with the characters we read about or see on TV. So like, I'm never gonna be a paranormal investigator looking at, you know, alien abductions. But I can live that through the show and sort of experience some of what that might be like. So I think there's perhaps that element of living vicariously, perhaps through wanting to see that relationship progress.

Find whatever story brings you joy. And if you didn’t catch The X-Files the first two times around and decide to check it out, remember it’s up to you how you see Mulder and Scully, and whether you ship it.

References

Gottman, J. & Silver, N. (2015) The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work: A Practical Guide from the Country's Foremost Relationship Expert. Harmony.

Nguyen, T., Khadadeh, M. & Jeong, D.C. (2023). Shippers and kinnies: Reconceptualizing parasocial relationships with fictional characters in contemporary fiction. Foundations of Digital Games (FDG), Vol. 32, p 1 - 12.