Alcoholism

What Consumers Should Know About Good-Better-Best Pricing

Marketers sell different priced products to customers hoping for heftier profits

Posted February 16, 2016

These days, good-better-best pricing is everywhere. When purchasing an airplane ticket, for example, passengers can buy the default coach ticket (good), pay for some extra leg-room by upgrading to “premium economy” (better) or pay through the nose and buy a business class seat (best). With all three tickets, the basic service is the same―aerial transportation from point A to point B. But the amenities (or the degree of discomfort suffered, for the cynical among us) vary.

Along similar lines, in bars, alcoholic drinks are priced low as rail drinks when the customer does not ask for any branded alcohol (good), higher as call drinks when a specific brand is requested (better), or highest as top shelf drinks for premium liquor brands (best). An Acura TLX vehicle comes in three versions: the base model has a 2.4 liter engine and an 8-speed automatic transmission (starting at $31,695; good); the mid-version has a 3.5 V-6 liter engine, and a 9-speed automatic transmission (starting at $35,320; better), while the high-end version is 3.5 V-6, 9-speed automatic with all-wheel drive (starting at $41,576; best). As these examples illustrate, when using a good-better-best pricing approach (also known in the trade as “tiered pricing”), the marketer sells several different versions of the same product to consumers at different price points and corresponding quality levels.

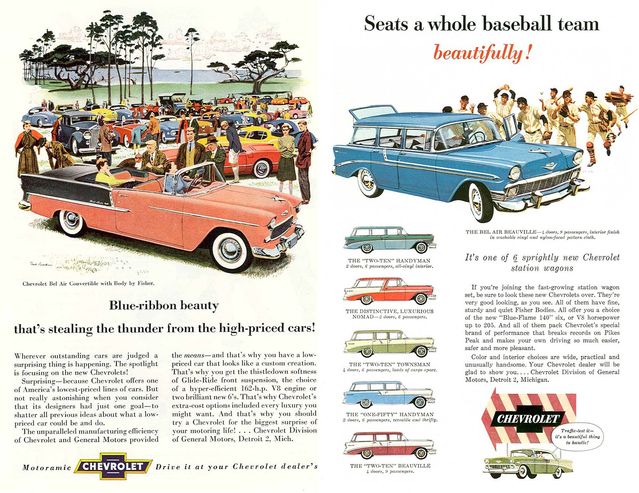

For decades, marketers have packaged and offered different products to different customer segments. See the Chevrolet ads from the mid-1950s. No one would mistake the hoity-toity target customers of the 1955 Bel Air convertible with the blue-collar family that would find the 1956 Handyman station wagon to be appealing.

But this way of designing and pricing products based on customer segment differences is changing. With the good-better-best pricing approach, marketers now systematically offer different product versions to pretty much the same customers based on how much they want to shell out on a given purchase occasion. For instance, someone flying for work may buy a business class airline ticket because her company is paying for it; but on another occasion, she may fly in coach when shelling out of her own pocket.

So what do shoppers need to know about good-better-best pricing?

1) Marketers want consumers to trade up from the good option to the better option or from better to the best option.

By offering different choices, at the first blush, it may appear that marketers have shifted the decision of which version to buy each time over to the customer. But the truth is that through subtle and overt signals, marketers encourage customers to purchase the more expensive option than the one they had in mind to begin with.

Take the case of pork chops. A grocery store uses good-better-best pricing, promoting a deal on thin-cut chops (the good version) in the meat case at a mouthwatering price. But the meat case display strategically exhibits thicker-cut (better) and pasture raised organic chops (best) right next to the cheap chops. In such a line-up, the thin-cut chops won’t hold their own for most shoppers. The goal of such overt comparison is to lure buyers towards the more expensive choices. Kent Harrison, marketing VP of Tyson Fresh Meats described the logic in this way:

"Retailers must make sure to stock their case with a variety of choices, to give consumers the option of moving up to the next tier of quality, which will also be an opportunity for the retailer to gain higher total dollar sales.”

2) Many consumers oblige the marketer and trade up to the more expensive better or best options without careful thinking.

Once shoppers have made up their minds to purchase something, they are relatively easy to persuade about which specific item to buy. They routinely change their minds at the point of purchase. Often times, the situation itself may make the trading up decision an easy one. For example, if someone else is paying for your airline ticket, upgrading to premium economy or business class makes sense on a long-haul flight. Or you may be at a bar and having a really good time with friends. In the midst of this fun, ordering a top-shelf drink instead of a cheaper rail drink feels like a natural decision (after all, it’s only a few dollars more!). Or you may justify the expensive choice to yourself in other ways―“After all, I don’t buy a new car every day, so I might as well opt for the version with the bigger engine and the all-wheel drive.”

Pricing expert Rafi Mohammed provided an interesting example of Southwest Airlines introducing a “Business Select” fare in which customers paid $10 to $30 more, receiving amenities such as priority boarding, faster passage through security lines, and a coupon for an alcoholic drink. In evaluating the introduction of this better option, Mohammed noted:

“In its first year, I estimate this best version increased Southwest’s revenue by $100 million and operating profit by 10%.”

Why do marketers push consumers away from the good option and towards the better and best options so hard? The answer is straightforward.

3) As consumers’ choice shifts from good to better, and from better to best, marketers earn heftier profit margins.

In most cases, the good option is the company’s bread and butter. For airlines, it’s the coach seats on their planes in which close to 90% of their passengers fly. For vehicles, it’s the customers who buy the base version of the car or truck. And for hotels, it’s the travelers who book the standard room on the property. The good options are core products sold to core buyers that allow companies to cover their costs and stay in business year after year. Not surprisingly, companies are conservative about how much they are willing to charge for their good options. They cannot afford to lose this core business, so they will usually restrict prices on the good option. But things are different for the other options.

When offering better and best options, such conservatism in pricing does not apply. By its very definition, customers interested in these more expensive choices are not as price sensitive. They are more conscious about factors like appearance, status, style, and performance. So companies can and do mark up these options to a much greater degree. Take the case of airline seats. On a flight from New York to London, an economy ticket may cost around $900, the premium economy ticket may cost $1,800 to $1,900 while a business class ticket may cost $4,000-5,000. Clearly, the incremental costs of offering the marginally greater leg-room, better meals, and free alcoholic beverages are not proportionally greater. So the airlines make much higher profits from these upgraded seats.

So what should consumers do?

Rather than evaluating actual prices of good, better, and best choices, consumers should focus on both price and quality differences between the choices. In some cases, the differences may justify an upgrade from the good to the better option, or from the better to the best. Paying a few hundred dollars more for being able to sit more comfortably and stretch out on a long trans-Atlantic flight may be well worth it for some fliers (especially when someone else is paying for the ticket). But in other cases, the higher price for the upgraded choice may not be justified. When mixed with Coke and smothered in ice cubes, a cheap rail rum that costs $2 per shot may be equally tasty and produce the same mellowness as a 50-year old Appleton Estate reserve rum costing $300/shot. The key is to pay attention and think through the value each option provides in relative terms, which few shoppers tend to do. Many times, the good option may be good enough.

I teach marketing and pricing to MBA students at Rice University. You can find more information about me on my website or follow me on LinkedIn, Facebook, or Twitter @ud.