Philosophy

How Stoicism Could Help You Build Resilience

Combining stoic philosophy and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Posted August 2, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Stoicism is an ancient Greek school of philosophy that inspired modern cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

- Stoics like Epictetus taught that it's not things that upset us but rather our opinions (cognitions) about them.

- People identify with Stoicism as a philosophy of life, which may be more permanent than skills learned in CBT or resilience training.

Stoicism is an ancient Greek school of philosophy. It was founded around 301 BC by a Phoenician merchant called Zeno of Citium, who embraced an austere philosophical way of life after losing his entire fortune in a shipwreck near Athens. Stoicism has become increasingly popular over the past few decades, in part, because of the rising popularity of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Psychotherapists began to rediscover Stoicism from the 1950s onward through the writings of Albert Ellis and what would become known as rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT).

Many of the principles incorporated in the theory of [REBT] are not new; some of them, in fact, were originally stated several thousand years ago, especially by the Greek and Roman Stoic philosophers... (Ellis, Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy, 1962, p. 35).

He was particularly interested in the Stoic philosopher Epictetus’ saying: “It is not things that disturb us but rather our opinions about them.” Ellis taught this saying, which highlights the role of our thoughts and beliefs (cognitions) in our emotions, to most of his therapy students and clients, and he quoted it in most of his books. As a result, it is one of the best-known Stoic sayings today.

Aaron T. Beck, the founder of cognitive therapy, subsequently opened his seminal book on that approach by describing the consensus among researchers that cognitions play a central role in our emotions. Then, like Ellis, he added:

Nevertheless, the philosophical underpinnings go back thousands of years, certainly to the time of the Stoics, who considered man’s conceptions (or misconceptions) of events rather than the events themselves as the key to his emotional upsets. (Beck A. T., Cognitive Therapy & Emotional Disorders, 1976, p. 3)

After it gained credibility in this way, there was a resurgence of interest in Stoic philosophy, leading to a wave of modern self-help books from the late 2000s onward, including William B. Irvine’s A Guide to the Good Life, Ryan Holiday’s The Obstacle is the Way, and Massimo Pigliucci’s How to be a Stoic, to name just a few.

Stoicism as Psychotherapy and Self-Help

It surprises many people to learn that psychotherapy is not a modern concept. Ancient Greek thinkers, from the time of Pythagoras and Socrates onward, had adopted a medical model of philosophy. They described what they were doing as a sort of talking cure, comparable to physical medicine but employing words.

There are many explicit references to this in ancient Greek literature, but the Stoics really embraced the concept of philosophy as psychotherapy. They wrote books wholly dedicated to the subject, such as the celebrated Therapeutics of Chrysippus, the school's third head.

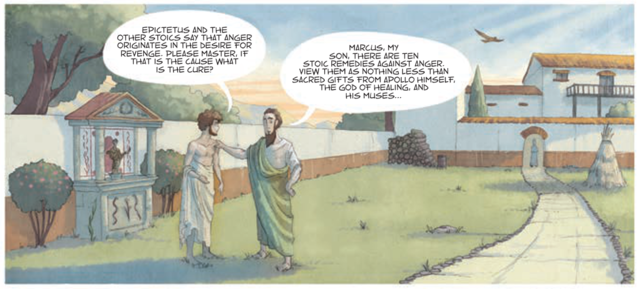

Most of these early books on Stoic psychotherapy are sadly lost, with one exception. We have an entire book on the Stoic therapy of anger by Seneca that survives today, called, simply, On Anger. In our graphic novel, Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, we describe ten anger management strategies listed by Marcus Aurelius and show how he applied them to the challenges of ruling as Roman Emperor.

Stoicism is a philosophy, though, not a psychotherapy. It would be more accurate to say that it contains within itself or encompasses a form of psychotherapy. However, philosophy is bigger than therapy. Stoic philosophy provides a whole worldview and set of moral values. Indeed, people tell me they’re drawn to Stoicism for several reasons:

- They view it as providing a Western alternative to Buddhism, yoga, and other Eastern philosophical traditions.

- It seems to offer them a secular and more rational alternative to Christianity.

- They find it offers a more practical alternative to modern academic philosophy.

- It resembles CBT and modern self-help, but they find it is broader in scope and offers a more complete philosophy of life.

Stoicism and Resilience

One of the reasons that some psychologists are interested in Stoicism today is that it may hold promise for what I like to call “The Holy Grail of mental health,” by which I mean prevention. As everyone knows, “prevention is better than cure,” and that applies not only to our physical health but also to our mental health.

Stoicism was certainly used therapeutically in the ancient world to treat existing emotional distress. For example, we have Stoic letters of the consolatio genre, written to help bereaved individuals cope with overwhelming feelings of depression. Nevertheless, there is far more emphasis on using philosophy as mental health prophylaxis, a preventative form of psychological training.

Today the main approaches to preventing future mental health problems are forms of emotional-resilience training, such as the Penn Resiliency Program (PRP). That involves learning psychological skills, usually drawn broadly from CBT, positive psychology, and problem-solving training.

Resilience is our capacity to “bounce back” from stressful life events, or at least to cope with them without being overwhelmed. An emotionally resilient person is able to cope better than average with challenging events such as job loss, divorce, physical illness or injury, bereavement, and so on.

For many people, “resilience” and “stoicism” are almost synonymous. However, it’s very important to understand that researchers typically use the term “stoicism” (lowercase) to refer to a set of coping skills, such as suppressing or concealing unpleasant emotions, which have been found problematic and potentially counterproductive.

That’s completely unrelated to “Stoicism” (capitalized), the ancient Greek school of philosophy, which has a much more nuanced theory of emotion and inspired CBT, with its known therapeutic benefits. We definitely don’t want to confuse “Stoicism” with “stoicism” if one is known to be good for our mental health and the other is potentially bad for us!

Training in CBT and related psychological skills works well to build emotional resilience, with one drawback. People tend to forget about or stop using the techniques after a year or two unless they’re given booster training sessions. That’s what makes Stoicism so intriguing: people tend to get into it long-term or even permanently. Stoicism is for life, not just for Xmas, you could say. People simply identify with it at a deeper level, as though it were a religion or philosophy of life like Buddhism or yoga.

It may also be because the Stoic writings that survive are masterpieces of philosophical writing, containing many quotable and easily remembered sayings. Stoicism asks us, moreover, not simply to use some self-help techniques but to embrace a set of ethical values and live consistently in accord with them. In other words, this ancient philosophy could hold promise as a framework for permanently acquiring CBT-like coping skills.

As some put it, compared to CBT or existing methods of resilience-building, Stoicism is sticky.

To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Robertson, D. ‘Stoic influences on modern psychotherapy’ in The Routledge Handbook of the Stoic Tradition, edited by John Sellars.

Beck, A. T., 1976. Cognitive Therapy & Emotional Disorders. New York: International University Press.

Ellis, A., 1962. Reason & Emotion in Psychotherapy. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel.

Reivich, K. & Shatté, A., 2002. The Resilience Factor. New York: Three Rivers.

Robertson, D. J., 2005. Stoicism: A Lurking Presence. Counselling & Psychotherapy Journal (CPJ), July.

Robertson, D. J., 2010. The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT): Stoic Philosophy as Rational & Cognitive Psychotherapy. London: Karnac.

Robertson, D. J., 2012. Build your Resilience. London: Hodder.

Still, A. & Dryden, W., 2012. The Historical and Philosophical Context of Rational Psychotherapy: The Legacy of Epictetus. London: Karnac.