Creativity

Why Peak Experiences Matter

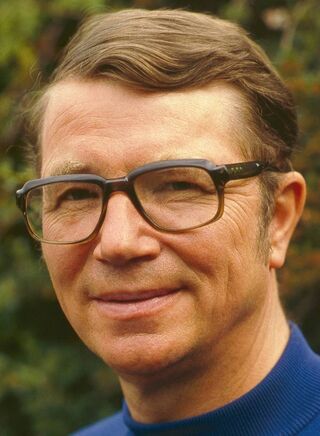

Colin Wilson and Abraham Maslow catalyzed each other's writings on creativity.

Posted June 8, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Colin Wilson had a major impact on Abraham Maslow's conception of creativity and self-actualization.

- Wilson regarded Maslow's work on peak experiences as "the secret of the next step in human evolution:"

- Meanwhile, Maslow praised Wilson's ideas on higher consciousness.

As Abraham Maslow’s biographer, I’m fascinated by the range of thinkers who influenced his psychological outlook. Among the most intriguing was the prolific British writer Colin Wilson. By the vagaries of fate or the subtle workings of destiny (take your pick), he was slated to write Maslow’s biography but forlornly abandoned it when Maslow suddenly died of a heart attack in 1970. Years later, inspired by Wilson’s books, including New Pathways in Psychology, based largely on Maslow’s ideas, I initiated the same project and happily completed it. In the meantime, we began corresponding actively about the man we both admired. Colin (we were soon on a first-name basis) was extremely generous in writing the lengthy foreword to Future Visions, Maslow’s key unpublished papers, which I edited and organized into a book that is still in print after 25 years.

Who was Colin Wilson?

Born into a working-class Midlands family during the Depression, he was an avid reader by his teenage years, especially interested in science and philosophy as paths to finding the meaning of life. Like his earlier compatriot H.G. Wells, who also came from an uneducated working-class family, Colin was utterly alienated from his social milieu. But unlike Wells, who apprenticed with the eminent biologist Thomas Huxley, Colin became a high-school dropout and held a long succession of menial “day” jobs. Convinced of his potential for literary achievement, he filled notebooks with ideas—and then, at the age of 24, he authored The Outsider, a 1950s bestseller on our need for meaning and purpose in a modern world fostering mass conformity.

Dubbed a “boy genius,” Colin became an instant celebrity in 1956—caricatured as a James Dean-type rebel—and was even considered for a biopic. Perhaps inevitably, such adulation didn’t last, and by the early 1960s, he settled with his wife Joy and their children in secluded Cornwall for the life of a freelance author-lecturer. His goal? To develop an incontrovertible and sustaining view of individualistic creativity and inner freedom.

Maslow initiated their relationship after reading Colin’s The Stature of Man (titled The Age of Defeat in its American edition). Delighting in its optimism about human potentiality (akin to the notion of self-actualization), Maslow sent him copies of his psychology articles. The two began a lively correspondence, repeatedly citing each other’s ideas in their ensuing books. Though both were intellectually-driven family men, they never became close friends, probably due to temperamental differences.

Maslow’s work on peak experiences, which Colin called “the secret of the next step in human evolution,” especially captivated him. He asserted that Maslow had scientifically proven that human consciousness has heights unimagined in conventional psychology and psychoanalysis—and that the joyful essence of peaks was central to their nature. Additionally, such mental states as apathy, boredom, and listlessness could now be understood as immature or faulty modes of consciousness—and, crucially in Colin’s worldview, quite correctible.

As for Maslow, he regarded Colin’s emphasis on the limited, limping quality of ordinary human consciousness as extremely insightful. In this context, he often cited Colin’s revelatory concept of the “St. Neot’s margin.”

Colin named it after the English village where his epiphany occurred: discovering while hitchhiking on a hot Saturday that not only had he been oblivious to his low-energy boredom, but that it could be overcome by an arousal of interest in one’s surroundings. In Colin’s case, such interest had arisen accidentally when two consecutive lorry drivers reported curious mechanical problems in their vehicles—” and suddenly my boredom and indifference (had) vanished.” This experience catalyzed Colin’s notion that most people habitually live far below their daily capacity for happiness, delight, and wonderment.

During Maslow’s final years, he became increasingly impressed with this notion, arguing therefore for the necessity of what he termed “cognitive re-freshening.” Such activity, he believed, could help sustain what he called plateau experiences, extended times of transcendent serenity. He also regarded re-freshening as vital for conquering lethargy toward loved ones. To do so, Maslow advised, it’s helpful to imagine that you’re seeing this person for the last time before death—a technique that probably emerged spontaneously after his initial major heart attack.

Maslow and Colin Wilson are now gone, but in contemporary psychology, Ellen Langer’s work on “mindfulness versus mindlessness” in everyday life provides a valuable path for extending their powerful insights.

References

Hoffman, E. (1999). The right to be human: A biography of Abraham Maslow, 2nd edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Hoffman, E. (1996). Future visions: The unpublished papers of Abraham Maslow. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lachman, G. (2016). Beyond the robot: The life and work of Colin Wilson. New York, NY: Tarcher/Perigree.

Langer, E.J. (1997). The power of mindful learning. Boston, MA: Da Capo Lifelong Books.

Langer, E.J. (2014). Mindfulness: 25th Anniversary Edition. New York, Boston, MA: Da Capo Lifelong Books.

Maslow, A.H. (1971). The farther reaches of human nature. New York, NY: Viking.

Maslow, A.H. (1979). The Journals of A.H. Maslow, edited by R.J. Lowry). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Tomalin, C. (2021). The young H.G. Wells: Changing the world. New York, NY: Penguin.

Wilson, C. (1959). The age of defeat. London: Gollancz.

Wilson, C. (1972). New pathways in psychology. New York NY: New American Library.

Wilson, C. (2004). Dreaming to some purpose: The autobiography of Colin Wilson. London: Century.