Extroversion

The Lives and Opportunities of Introverts and Extraverts

A conversation about personality and how it shapes our fortunes.

Posted July 1, 2020 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

By Kendall Vidal and Luke Smillie

The following conversation took place between Kendall Vidal, a student of Great Lakes College Senior Campus, at Tuncurry, and Luke Smillie, an associate professor of personality psychology at The University of Melbourne.

KV: How would you describe an introvert?

LS: The prototypical introvert is a quiet and reserved person, who prefers lower levels of social stimulation and activity. Contrary to popular belief, introverts are not necessarily reflective, contemplative, or intellectual. Some introverts happen to have these characteristics, but that isn’t what makes them introverts.

KV: How would you describe an extravert?

LS: Basically, as the opposite of an introvert. Less quiet, less reserved. Extraverts are talkative, sociable, outgoing, behaviourally active, and socially dominant.

KV: Is "extravert" the correct spelling? Or should it be "extrovert"?

LS: The correct spelling is "extravert." "Extrovert" is a misspelling that has gradually become accepted. Carl Jung coined the term about a century ago, combining the Latin terms extra (meaning "outside"), and verte (meaning "to turn"). So an extravert is "turned outward." (Extro, by contrast, has no meaning in Latin.)

KV: Is there a spectrum of introversion, and can people be a combination of both introvert and extravert?

LS: This is a great question! There are a couple of parts to my answer:

First, introversion-extraversion is indeed a spectrum, by which I mean it’s a continuous dimension along which people can vary, from introversion at one end to extraversion at the other, a bit like height. Like virtually all psychological characteristics, differences between extraversion and introversion are continuous rather than categorical differences. And just as people can’t be both tall and short, they can’t be both an extravert and an introvert. But they can fall somewhere in the middle—being neither very introverted nor very extraverted—and perhaps that can feel like being a bit of both.

Introversion-extraversion is also a spectrum in another sense: Rather than a single dimension, it is really a cluster of closely related dimensions. Here, the analogy with height breaks down. If a person is 160cm tall, that’s all the information you need to describe their height. But with introversion-extraversion you can provide increasingly finely-grained descriptions. And two people can be equally introverted but in different ways. One might be unassertive but quite sociable; the other might be more assertive, but more aloof. This is because personality traits are “hierarchically organised," with very specific tendencies (e.g., being "talkative") clustering together to form broader traits (e.g., being "extraverted").

KV: How many people in Australia would you estimate to be introverted?

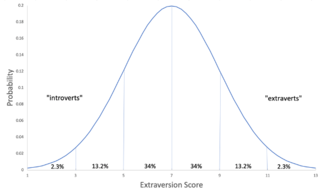

LS: Well, introversion-extraversion is "normally distributed," like a bell curve, so most people fall in the middle—about 70% of the population. This leaves roughly 30% of people in the "tails" of the distribution; so, I'd say about 15% of Australians would be "quite introverted." We can see this in the figure to the left.

KV: How do introversion and extraversion present in adolescents?

LS: During late childhood and adolescence, introversion-extraversion reflects one’s typical levels of behavioural activity, talkativeness, and the expression of positive emotions. Your average 15-year-old extravert is loud, chatty, laughs a lot, socially "attention-seeking," and energetic. Your typical 15-year-old introvert simply expresses fewer of these characteristics, or expresses them less often. They are quieter, calmer, might seem shy (although shyness is a bit different to introversion), and don't like being the centre of attention. As people age, this pattern shifts a little. Specifically, extraversion tends to become a bit more about social boldness—being assertive, able to lead, take charge, and exhibit confidence.

KV: Do you believe this statement: "Introverts lack opportunities as they don't put themselves forward"?

LS: It seems there would be some truth in that idea, and I’d certainly believe any introvert who told me it was their personal experience. Because introverts tend to be less bold and talkative, they seem more likely to be overlooked, and indeed, less likely to "put themselves forward," as you say. I’m aware of little scientific evidence for this, but lots of people who identify as introverts feel this kind of thing happens to them. Susan Cain’s popular book, Quiet, touches on these kinds of experiences.

KV: Do you think that one’s level of introversion-extraversion has an influence on promotion and leadership opportunities in employment?

LS: There is some evidence that might be in line with this. Specifically, higher extraversion predicts better performance in leadership positions. This may mean extraverts are simply better leaders, but could also mean they are afforded more opportunities and support in these roles. That would make sense if extraverts generally fit people’s stereotypes of a good leader.

KV: Is there a difference in how introverted men and women are perceived?

LS: Great question: I think it is quite likely that extraverted men and women are perceived differently. Specifically, much research over the years has shown that ‘agentic behaviour’ (i.e., behaviour that is bold, dominant, or assertive—all key components of extraversion), is a quality that people tend to admire in men but dislike in women. Assertive men are perceived as strong leaders; assertive women are often seen to be bossy. It's a problem many women know well (Hillary Clinton comes to mind!).

KV: Do these personality differences influence a person's social inclusion and does it have a positive or negative influence in their lives?

LS: Another great question. It is definitely the case that extraverts cultivate larger and more satisfying social circles, and that their social lives are in some ways 'richer' than those of introverts. Extraversion also seems to have a positive impact on people’s lives in terms of their general well-being: No matter how you measure happiness—well-being, meaning, quality of life, etc.—extraverts fare better than introverts. Research that connects these dots together includes the finding that extraverts perceive they contribute more to their social world, and feel happier and more satisfied as a result. Similarly, extraverted students appear to cultivate more rewarding friendships at university, leading to higher well-being by graduation.

In saying all this, there is an important caveat: extraversion and introversion are opposites, but the knowledge that extraverts typically have happier and more socially rich lives than introverts doesn’t mean that introverts have miserable, lonely lives. This seems counterintuitive but can be explained by the fact that these differences are relative. In the context of a healthy, general population, most people do pretty well in terms of social inclusion and quality of life, and that includes introverts—even if extraverts fare a little better.

References

Smillie, L. D., Kern, M., Uljarevic, M. (2019). Extraversion: Description, development, and mechanisms. In D. McAdams, R. Shiner, & J. Tackett (Eds.), Handbook of Personality Development, Guilford Press.