Coronavirus Disease 2019

Mixed Emotions Are Much More Common Than Negative Ones

Even during the pandemic, few people report purely negative emotions.

Posted May 13, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Much has been written on the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on negative emotions, such as rising anxiety and the loneliness of self-isolation.

But while things may seem all doom-and-gloom, new data reveals that it’s surprisingly rare for a person to experience purely negative emotions. Instead, most instances of negative emotion occur as part of mixed emotions—even during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Psychologists have traditionally viewed emotions as falling along a single dimension, ranging from positive (such as happy or excited) to negative (such as sad or anxious). This implies that at any given moment we feel “good” or “bad," but not both. Positive and negative emotions have even been said to mutually inhibit each other—so if you are enjoying your day but receive some bad news, your positive mood is supposedly replaced by a negative one.

However, an alternative view suggests positive and negative emotions vary independently, and can thus co-occur. This allows for the experience of mixed emotions, such as feeling both happy and sad, or nervous but excited, at the same time. There is now extensive evidence for the existence of mixed emotions. And new data reveals they may be surprisingly common.

Mixed Emotions Are Much More Common Than Purely Negative Ones

A recent study led by Kate Barford (an author of this post) examined how mixed emotions arise in day-to-day life. Across three participant samples, Barford and her colleagues found mixed emotions typically emerge when negative emotions intensify (such as following a negative event), and blend with ongoing positive emotions.

Thus, bad feelings do not always extinguish positive ones, like flicking off a light switch. Rather, they more often transform a positive mood into mixed emotions.

Intriguingly, the study also found that purely negative emotions (the absence of any concurrent positive emotions) are surprisingly rare. In all three samples, participants reported purely negative emotions less than 1 percent of the time during one-to-two weeks of daily life. In contrast, mixed emotions were reported up to 36 percent of the time.

This shows that our negative emotions are rarely so strong that they overwhelm our positive ones, at least during everyday circumstances.

Mixed Emotions During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Currently, most of us are not facing "everyday circumstances." As the coronavirus spreads around the globe many nations have gone into lockdown, and some say that life might never return to normal. Surely negative emotions would dominate during such ominous times?

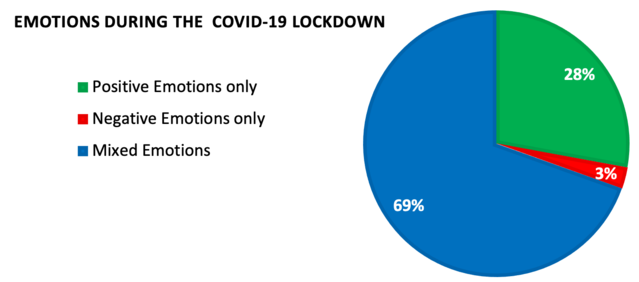

To find out, we surveyed 854 Australian residents about their emotional experiences in late March, as government restrictions were introduced. In line with widespread reporting, we found that 72 percent of our sample were indeed experiencing negative emotions.

However, almost all of these people also reported feeling positive emotions, such as joy and contentment. And only 3 percent of our sample reported purely negative emotions as the crisis unfolded. In comparison, around 70 percent of people reported feeling mixed emotions—much higher than previously found by Barford and colleagues.

The high rate of mixed emotions during the COVID-19 crisis may be the result of increased negative emotions that blend with positive ones—as Barford and her colleagues previously found.

Mixed emotions might also arise from conflicted thoughts and feelings about our current predicament. For instance, we might dislike social distancing, but approve of it for the sake of our collective health. Or we might enjoy the novelty of altered working arrangements (such as working from home) even though they can be disruptive. Indeed, almost half of the participants in our sample reported they enjoyed tackling some of the challenges of lockdown.

Who Experiences Mixed Emotions?

Our emotions are not determined simply by our circumstances, but also our personalities. In the study by Barford and her colleagues, individuals scoring lower on trait emotional stability (or, equivalently, higher on neuroticism) experienced more mixed emotions. This was because these individuals were more susceptible to the increases in negative emotion that blended with ongoing positive ones, resulting in an overall bittersweet experience.

This same finding emerged in our survey in the context of COVID-19. We found that lower emotional stability was a stronger predictor of mixed emotions than other situational and demographic factors. These factors included age (younger people experienced more mixed emotions) and the extent of disruption to one’s day-to-day activities.

Could Mixed Emotions Be Helpful?

Interestingly, psychologists think mixed emotions may have some benefits. Specifically, whereas purely negative emotions can lead us to disengage from our goals, mixed emotions may prepare us to respond to uncertain situations in flexible ways. There is even evidence the experience of mixed emotions may cushion the impact of uncertainty on our well-being.

At a time when doom and gloom have dominated the headlines, the high prevalence of mixed emotions during this pandemic may be good news for our mental health.

This post also appears on The Conversation and was written with my colleagues Jeromy Anglim, Kate A. Barford, and Peter O'Connor

Facebook image: Alliance Images/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: Prostock-studio/Shutterstock

References

Barford, K. A., Koval, P., Kuppens, P. & Smillie, L. D. (in press). When good feelings turn mixed: Affective dynamics and Big Five trait predictors of mixed emotions in daily life. European Journal of Personality. doi: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/per.2264