Friends

The Rewards of Patience in Troubled Times

How reconnecting with family, friends, and colleagues lifts the human spirit.

Posted August 14, 2020

The Songhay people of Niger and Mali in West Africa have a wonderful idiom: andunya kala suuru: “life is patience.” When I began ethnographic research in the West African Republic of Niger, Songhay elders advised a neophyte anthropologist to be more patient—advice that I, like most young people in the race to "make it," refused to take. Despite my stubborn persistence to rush through my life as a junior scholar, the elders repeatedly told me: “If you are persistent one day your path will open.” This advice has always been spot on.

Even so, It is hard for anyone to be patient in these pandemic times. Most of us have been in lockdown mode for many months and there’s no end in sight. Most of us have been physically separated and/or socially distanced from our family, friends, and colleagues. When will we be able to hug our children and grandchildren? Should we invite family or friends into our houses, risking potential exposure to coronavirus? How can we restore the frayed bonds of social trust?

Cut off from our everyday social contacts, it’s easy to slip into a state of alienation. In a recent podcast, even former First Lady Michelle Obama, a paragon of psychological adjustment, admitted to recent bouts of low-grade depression.

Covid-19 has changed the way we live and for many of us that fact has made us despair for the future. We all know people who are suffering. Many of us wonder, when, how, or if our social life will change. Will post-pandemic social life be better, worse, or the same as pre-pandemic social life? It’s impossible to know.

One consequence of our current period of social isolation is that the pace of life has slowed down. This new reality gives many of us more time to think about the meaning and meaningfulness of our lives. What can we do to enrich our lives in troubled times?

Let me describe a recent experience that substantially lifted my spirits. Prior to the pandemic, I had been in contact with the daughter of a dear colleague who passed away many years ago. I have known A and her sister L since their childhood. Like me, their mother, a highly respected French anthropologist, did ethnographic fieldwork on religion in Niger, a shared experience that made us kindred spirits. That existential linkage meant that I have always felt a special connection to A and L. From a distance, I proudly observed them grow into wonderfully accomplished adults. L is a professor of philosophy. A is an award-winning filmmaker.

In a recent e-mail A wrote me about her mother’s diaries and described some events that had emerged, or so she thought, from her mother’s experience in Niger. She asked for advice, which I gladly gave to her. Re-reading her mother’s fieldnotes also inspired A to begin a project with diasporic Nigeriens in Belgium. A made contact with the Nigerien community in Brussels and told the Nigeriens there, who were mostly Songhay and Zarma people, about my research in Niger. They wanted to meet me and A arranged a meeting several days ago by way of WhatsApp.

With A beaming in the background, I talked with Z, the president of the Brussels Nigerien cultural association. We spoke in Songhay: greetings, proverbs, stories of our travels, and talk of people we knew in common. The conversation brought back memories of wonderful encounters, deep friendships, and life-changing events. The social warmth of that conversation brightened my spirits, sparked my creative energy, and gave me hope for a better future.

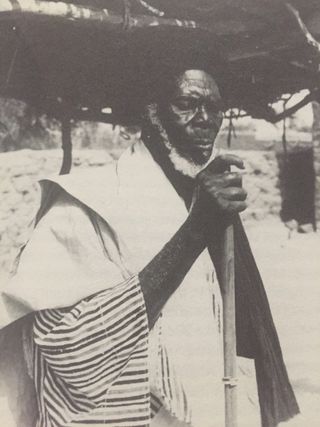

That unexpected conversation also reminded me of the deep power of (fictive) kinship to sustain the human condition. Soon after our conversation, Z sent me a photo of my Songhay mentor’s great grandson who now lives with his wife in Brussels. Seeing that photo and having established a multicultural and multi-generational connection filled my heart with joy, compelling me to push the misery of contemporary American social life into the background of my consciousness.

Although this story may seem like a rather inconsequential episode in everyday life, the lesson from it is that small interpersonal gestures—taking the time to reach out to family, friends, and colleagues—can have powerfully affirming personal and social results. They can make us feel better about our lives, give us a sense social renewal, and restore frayed bonds of social trust. They remind us that in the long sweep of history, the social and psychological misery of 2020 is but a brief moment. If we are patient, as my Songhay mentors liked to tell me, our paths will eventually open up to better days and a better world.

Andunya kala suuru.