Jealousy

Jealousy as a Narcissistic Wound

The normal, the projected and the delusional

Posted November 5, 2016

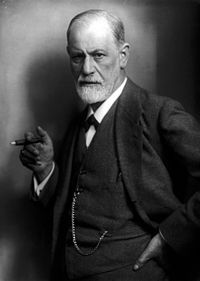

Sigmund Freud is perhaps best known for his work on dream interpretation and the division of the self into the super-ego (the moral voice), the ego (the acting persona) and the id (the subconscious). However, he has written on numerous other topics, including jealousy.

His analysis of jealousy is, if not entirely sound, then at least on the right track. Jealousy, he says, is a complex emotion that can be divided into the following components:

- Grief of a loss.

- A narcissistic wound.

- Feelings of enmity against the successful rival.

- Self-criticism owing to the fact that you hold yourself accountable for your loss to some extent.

Let us look closer at the four conditions. Although Freud refers to this as an analysis of the notion of jealousy, none of the components seems necessary or jointly sufficient for jealousy to obtain.

Jealousy is no doubt often associated with grief. But grief of what? In some cases, it may be grief of a loss of your partner to another person. In other cases, it may be a loss of the partner's trust or a belief to the effect that you "own" the other person. But jealousy can arise even when nothing is lost. Some people get jealous for no good reason at all.

Turning to the second condition, a narcissistic wound is a wound to the ego, a kind of emotional pain. This could be a component of the grief of the loss, when there is a loss, or perhaps a grief related to a potential or an impending loss. Could jealousy occur without pain? It likely could. It is not infrequent to experience anger and pain in an alternating fashion when one is grieving.

Turning to the third condition, hostility towards the successful rival often is not a component of jealousy. There may be no successful rival, and even if there is, the blame may be directed entirely toward the partner rather than the rival.

Finally, the fourth condition is not necessary, as self-criticism may not occur. There are cases where you feel responsible for having pushed away your partner and feel blame as part of your jealous feeling. But there are many other cases in which you may feel that you have done everything you could to keep the relationship in good shape. In such cases, you may not feel any responsibility at all.

None of these conditions then is necessary for jealousy to occur. This is unsurprising. Complex emotions are not subject to logical analysis, because they are psychological states. A psychological state that feels like jealousy to one person may not feel like jealousy to another, and felt jealousy could be grounded in one type of psychological state for one person but have its seat in another type of psychological state for another person.

Other complex emotions work similarly. Grief is sometimes said to be composed of surprise, denial, anger, sadness, bargaining and acceptance. But not everyone goes through all of these stages in the healing process. Some people may feel grief differently altogether. For instance, you may simply feel numb.

The four conditions discussed by Freud are not jointly sufficient for jealousy to obtain, either. Some people report feelings of helplessness and disgust as strong components of jealousy. The very thought of your partner having sex with another person may pacify you and make you nauseas and revolted. Other people become motivated rather than passive and go on a revenge mission or a mission to get the partner back.

Freud argues that jealousy is never a rational emotion. For it to be rational, he says, it would need to be "under the complete control of the conscious ego." But it is not, because it has its seat in the subconscious. Freud's account of rationality does not appear to be sound, however. Beliefs are not under the complete control of the conscious ego. We cannot just decide to believe something (pace William James). Yet one can certainly have rational and irrational beliefs. Furthermore, a jealous response to a cheating partner seems perfectly rational.

While Freud does not think jealousy is ever completely rational, he thinks that it can be normal, projected or delusional. Normal jealousy, according to Freud, is competitive in nature. So, it would likely need to have a motivational component, causing you to seek to win your partner's interest back or take revenge.

Projected jealousy is jealousy that originate in your own infidelity or thoughts about cheating. Because you have those thoughts. you mistake signs that aren't really signs that your partner is having an affair for signs of that they are, or you mistake innocent gestures for signs that someone is trying to seduce your partner. Or: owing to your own non-monogamous nature, you might simply become more sensitive to signs of infidelity and discover that your partner is in fact cheating or about to leave you for someone else.

Finally, delusional jealousy—which is a form of morbid jealousy—is a form of paranoia. If you are jealous because you believe that your partner is cheating or will cheat eventually, despite there being no evidence, then you suffer from delusional jealousy. In persecutory paranoia, a person who suffers from delusional jealousy will see signs of infidelity or threats to the relationship everywhere: the partner's brief gaze at another man or woman, an accidental touch of another person's hand or any form of engagement with the opposite sex (or same sex in the case of homosexuals).

References

Freud, S. "Certain Neurotic Mechanisms in Jealousy, Paranoia and Homosexuality," The Psychoanalytic Review (1913-1957)12 (Jan 1, 1925).

Berit "Brit" Brogaard is the author of On Romantic Love