Intelligence

Minding Meat Versus Artificial Intelligence

Do humans alone have minds?

Posted March 6, 2018

Among many definitions of the word ‘menagerie’ is this one: “any varied collection, especially one that includes things that are strange or foreign to one’s experience.” When applied to the notion of mind, we must confront a profound question that is rooted in philosophy, engaged by evolutionary biology, and projected into the developing realm of artificial intelligence: namely, do humans alone have minds?

Exploring this issue in my blog will take us many places. My first two postings dealt with current events and findings: the role of Pavlovian conditioning in adaptive behavior and the role of operant conditioning in the development of human-made objects like the violin.

Here, I want to set the stage for several upcoming posts by reviewing some relevant history: so, I will now share the astute observations of George John Romanes (1848 – 1894). Romanes was a close friend and research assistant of Charles Darwin (1809 – 1882), each of whom sought evidence of mental continuity between humans and nonhuman animals. Romanes wrote the following lines concerning the daunting challenge of founding a natural science of mind (1883, p. 3):

“[B]y mind we may mean two very different things, according as we contemplate it in our own individual selves, or in other organisms. For if we contemplate our own mind, we have an immediate cognizance of a certain flow of thoughts or feelings…. But if we contemplate mind in other persons or organisms, we have no such immediate cognizance of thoughts or feelings. In such cases we can only infer the existence and the nature of thoughts and feelings from the activities of the organisms which appear to exhibit them. Thus it is that … in our subjective analysis we are restricted to the limits of a single isolated mind which we call our own, and within the territory of which we have immediate cognizance of all the processes … that fall within the scope of our introspection. But in our objective analysis of other or foreign minds we have no such immediate cognizance; all our knowledge of their operations is derived … through the medium of ambassadors – these ambassadors being the activities of the organism. Hence it is evident that in our study of animal intelligence we are wholly restricted to the objective method.” This objective analysis of behavior and its determinants is called “behaviorism.”

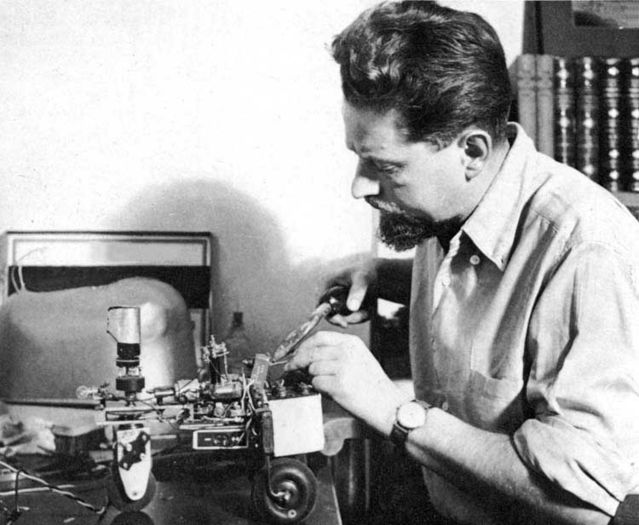

Behavior is thus central to any analysis of inferred mental or cognitive activities – not only in the case of humans and nonhuman animals, but also in the case of artificial devices. Consider the pioneering efforts of William Grey Walter (1910 – 1977) to create mechanical models that were capable of simulating the behavior of living beings – what we commonly call robots.

As a renowned neurophysiologist, turned cybernetician and robotician, Grey Walter was positively persnickety when it came to assessing the merits of simulations. To him, superficial resemblance was not enough for a robot to make the grade: “Not in looks, but in action, the model must resemble an animal. Therefore it must have these or some measure of these attributes: exploration, curiosity, free-will in the sense of unpredictability, goal-seeking, self-regulation, avoidance of dilemmas, foresight, memory, learning, forgetting, association of ideas, form recognition, and the elements of social accommodation. Such is life (1963, pp. 120 – 121).” Modeling these various mental functions provided Grey Walter a task that occupied the latter portion of his illustrious career.

It is instructive to see how these two different challenges contrast with one another: similarity in superficial resemblance and similarity in action or function. The work of Jacques Vaucanson and Grey Walter elucidate that challenge.

Vaucanson (1709 – 1783) was a distinguished French engineer who sought to answer two intriguing questions (Riskin, 2003). Which aspects of real creatures can be reproduced in machinery? What do such automata reveal about real creatures?

Vaucanson’s most celebrated creation was a mechanical duck, which became the most talked-about bird in all of Europe after it was unveiled in 1738. What was so special about Vaucanson’s mechanical duck? It had a weight-powered mechanism of over 1,000 movable parts that was hidden inside the bird and the pedestal on which it stood. Each wing had over 400 articulated pieces. And, the duck’s many and varied actions included: drinking, dabbling, gurgling, rising, crouching, stretching and bending its neck, plus moving its wings, tail, and feathers. All of these elaborate actions were most entertaining. But, the duck’s greatest achievements were that it ingested grain and, after a suitable interval, it defecated!

Vaucanson’s famous avian automaton is sometimes called The Digesting Duck. But, this nickname turns out to have been a patent misnomer. The duck did not digest food at all – it was a fraud! The ingested food actually progressed no farther than the base of the duck’s neck. Fake excrement – that had earlier been loaded into a hidden repository near the duck’s tail – was expelled after a programmed delay.

Some 200 years later, Grey Walter put his Cybernetic Tortoises on display. They exhibited two central elements of intelligent action: they were goal-directed (they moved toward light and ceased doing so when they reached the light) and they avoided obstacles that blocked their way to the goal. Video of Grey Walter’s original tortoises is available as is video of recreations of these devices. The visible success of these remarkable machines was the result of simple mechanics and electrical circuitry which pales by comparison with today’s technology.

Nevertheless, decades later, the well-known roboticist Rodney Brooks expressed disappointment at his own efforts in light of Grey Walter’s achievements. “Grey Walter had been able to get his tortoises to operate autonomously for hours on end, moving about and interacting with a dynamically changing world…. His robots were constructed from parts costing a few tens of dollars. Here at [my own research center], a robot relying on millions of dollars of equipment did not appear to operate nearly as well. Internally it was doing much more than Grey Walter’s tortoises had ever done – it was building accurate three-dimensional models of the world and formulating detailed plans within those models. But to an external observer all that internal cogitation was hardly worth it (2002, p. 30).”

Forced to decide whether minding machines exist, we should have little reason to doubt that humans and animals qualify – they are indeed biological machines. We might confidently claim that minding mediates the complex changes in behavior that humans and animals exhibit. Minding’s their business! We might therefore call them “minding meat” or “meat machines” (Smith, 2005). As powerful as we may construct them, or they may eventually construct themselves, however, it may never be the case that artificial devices will duplicate nature’s own minding machines. Yet, they may serve as useful proving grounds for mechanistic accounts of intelligent action – as envisioned by both Vaucanson and Grey Walter. Time will tell.

References

Brooks, R. A. (2002). Robot: The future of flesh and machines. London: Penguin.

Riskin, J. (2003). The defecating duck, or, the ambiguous origins of artificial life. Critical Inquiry, 29, 599-633.

Romanes, G. J. (1883). Animal intelligence. New York: Appleton.

Smith, C. U. M. (2005). Book review essay. How the modern world began: Stephen Gaukroger’s Descartes’ system of natural philosophy. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 14, 57-63.