Trauma

The Testimony and Teachings of Survivors

Traumatic transmission and healing.

Posted October 31, 2020

Few survivors of the Jewish Holocaust remain, the last witnesses to a group trauma that exceeded in scale the limits of most human experience. The Handbook of Psychoanalytic Holocaust Studies: International Perspectives (2019), edited by psychoanalyst Ira Brenner, educates readers on the legacy of the Shoah with first-hand accounts of survivors, their children, and grandchildren.

Speechlessness in the face of catastrophe is an early theme of the book, a paradoxical tension reflected in its title. “Handbook” rests uneasily next to “Holocaust,” an experience that can hardly, if ever, be fully grasped. How can something be put into words that is beyond their containment? The experience of the Holocaust defied conventional terminology. The word “genocide” was coined in the wake of WWII in attempt to encapsulate the horror.

Dori Laub (1937-2018), a child survivor, describes how a traumatic event of such magnitude undermines individual thought processes. Any traumatic experience overloads sense perception and confuses one’s relation to time and space, coordinates typically used to organize psychic reality and interpersonal relations. Associative links that characterize usual memories are obliterated, explains Laub, especially with severe trauma.

As with war veterans, language failed concentration camp victims, particularly in the first decades after WWII when mental health professionals minimized the psychological effects of the atrocities committed. Many survivors, like military war veterans, partially relive their sufferings in order to tell them. Without words they somaticize the pain. As psychiatrist Henry Zvi Lothane describes, in place of language post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the chronic reliving of traumatic experience and memories as flashbacks, waking hallucinations, nightmares, and other intrusive scenes of agony.

A moving first-hand account by psychiatrist Robert Krell conveys what it was like as a hidden child for three years until his liberation at age 5. The gravity of trauma inflicted on children during the Nazi persecution of Jews is evident in the 90% death rate. Krell writes of a childhood in which terror was intimately entwined with daily existence. Crying or complaint was life-threatening. “We had lost the privilege of growing up as children steeped in play and security," he recounts. Krell says he became an “elderly” child, encumbered by an accelerated sense of maturation and responsibility, as with other child survivors, many of whom assumed the caregiving role for regressed adults.

The European Jewish children who survived found refuge in convents, monasteries, sewers, caves, and forests. Many, like Krell, were rescued by Christian families. Krell writes that in order speak up in later life, “child Holocaust survivors had to overcome the initial post-war experience of being instructed to forget the past, and being told they had no memory and therefore did not suffer.” In his view, healing required some salvaged optimism regarding humanity, a fragment of good prewar memories and strength from internalized secure attachments. Secure parental attachment was one of the most significant factors in enabling resiliency.

The central section of the book addresses the transmission of trauma across three generations and therapeutic interventions. Until this publication, there has been little written about the impact of the Holocaust on the third generation. Psychologist Rivka Bekerman-Greenberg details her group therapy work with third-generation survivors. Her treatment provided containment for overwhelming emotion and uncovered recurrent themes of secrets and silence. Participants reported complex struggles in separation-individuation, a period of time when the infant separates from the mother or primary caregiver at about four months to three years of age. In this phase of development, elaborated by psychoanalyst Margaret Mahler, the infant emerges from symbiosis with the mother to develop psychological separateness and individuality. While tendencies to remain fused with parents coexist with the drive to separate throughout a person's life span, separation becomes a more complicated struggle for those who receive the unprocessed trauma of their ancestors. Children of survivors were preoccupied with their parents’ sufferings and often felt a responsibility to live as extensions of them. The important value of family caused debilitating demands and pressures that forestalled autonomy.

One of Bekerman-Greenberg’s patients communicated feeling “dead alive,” unconsciously trapped in the trauma of previous generations. Second and third-generation survivors describe how unmetabolized emotion invaded their internal world and interfered with the formation of individual identity. Group members conveyed confusion regarding life direction and purpose, diminished relational satisfaction, and feelings of emptiness and dread. Psychologist Eva Fogelman, a second-generation survivor ("2G") says, “The 2Gs grew up feeling different. They did not have grandparents or extended families for celebrations, and holidays became mournful remembrances.”

When the trauma of the Holocaust is passed across generations descendants feel compelled to live in the past, based on the unconscious fantasy of saving and restoring lost loved ones. As child psychiatrist Judith Kestenberg describes, they hold the injury of the past generation inside them and revisit it as if existing in a “parallel time" or pulled through a “time tunnel” to another temporal zone and experience. In the words of Social Science Professor Yolanda Gampel, descendants of survivors “play the part of the perished family members, not only unconsciously living the illusion that they are protecting their parents from having to confront an irreparable loss, but also going through the work of mourning in their stead.”

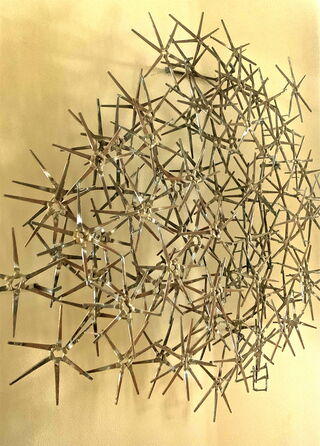

The mourning process for those who survive communal disasters is different from that of individual loss. Mourning the loss of a group of people requires community, advises Fogelman. Grieving shared trauma cannot be done in isolation. Anna Ornstein, a child survivor and psychoanalyst, points out how those who suffer communal catastrophes seek out the sites of monuments, the pages of memoirs, spaces of music, sculpture, and paintings “because of their power to elicit the dreaded but also deeply desired pain of grief … because it is only then that the numbness that isolates the bereaved from his/her surroundings can be overcome.”

Many authors of this collection emphasize the sense of belonging created by survivors’ support groups in the early 1980s, societies and conferences such as the Hidden Child Conferences and projects such as Kestenberg’s pioneering project for child Holocaust survivors, “The International Study of the Organized Persecution of Children.” Such communal events provide a social support system and source of healing. Through such gatherings an important shift from personal to collective memory takes place. Survivors’ voices have also contributed to public memory through testimonies to Holocaust Archives and through a commitment to education and social activism. The Western, and particularly American, focus on individuality tends to obscure the importance of the collective and mutual interdependence.

Across this collection of essays authors identify many sources of resilience. A late section on “Creativity” is devoted to film, literature, opera, theater, and poetry. Trauma can be mitigated through aesthetic means. Creativity is the “transformative agent,” says Ornstein. The creation of art is the unconscious recreation of a lost and broken world. Aesthetic work brings harmony to what has been obliterated, chaotic, arrhythmic. What is ugly, criminal, even evil—can be integrated and remade as a whole object in the work of a painting or story or aria. “Creative self-expression provides an opportunity to mourn, to memorialize, to find meaning and to regain some sense of continuity and connection,” opines psychologist and second-generation survivor Sophia Richman.

Fogelman states that the film and literature made by the “2 Gs” in large part accounts for the group’s changing identity. Even more, she argues that members of this generation of survivors are role models for other historically traumatized groups, helping others who have suffered together know how to mourn and re-engage processes of self-actualization.

As one author points out, a person may survive the Holocaust but no one ever escapes it. Healing is a lifelong endeavor and has profoundly influenced the career choices of many of these contributors guiding them toward work in reparative professions such as psychology, teaching, medicine, art, and social justice.

This intimate collection highlights how living with an exquisite consciousness of death inspires one to see through life’s trivialities. An awareness of finitude can allow an individual to live a more purposeful life, deeply felt.

References

Brenner, I. (Ed.). (2019). The Handbook of Psychoanalytic Holocaust Studies: International Perspectives. Routledge.