Psychology

Paranoid Parenting in Modern Society

Bereft of traditional folk psychology modern parents need expert help—but whose?

Posted February 14, 2020 Reviewed by Chloe Williams

Frank Furedi’s Paranoid Parenting has the subtitle: Why Ignoring the Experts May Be Best for Your Child. In a previous post, I described psychology today in terms of scientific versus folk and popular versus official psychology. In the light of these distinctions, I would have to agree with Furedi’s subtitle but might have expressed it in terms of Why Ignoring Official Psychology May Be Best for Your Child, and my previous post explains why.

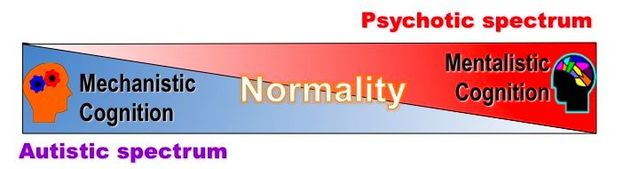

In another post, I argued that modern Western industrial societies have become collectively and culturally "autistic." This is measured by the Flynn Effect, given that IQ tests test mainly what I would call mechanistic cognition.

But the worrying implication of the diametric model (below) is that, if we are two standard deviations brighter in mechanistic intelligence compared to our great-grandparents, then we might be correspondingly less clever than them where mentalistic intelligence is concerned. This could explain a lot about the modern world, but it definitely explains what Furedi is complaining about if you consider parenting skills as a key component of mentalistic intelligence.

Modern societies produce specialized mentalities to go with occupational specialisms and prescribe different education—or at least training—for different jobs or professions. Add to this rapid, radical social change and mass immigration and you have a situation where it is as challenging for people to read the minds of others in their own society as travellers find reading those of natives of a foreign country. Inevitably, common folk psychology would be unlikely to survive in such a social milieu, and parents, in particular, might turn to psychology of other kinds for help (not least, posts on Psychology Today).

This might explain the modern addiction to reading about psychology and following the prognostications of psychology gurus, experts, and psychotherapists. Nowhere has this been more so than in relation to child-rearing, where the shift away from traditional families and women entering the workforce may have contributed to parents—and perhaps mothers, in particular—becoming bereft of family folk psychology and traditional child-rearing skills such that they must resort to books, magazines, and the internet to compensate. What once would have been handed down from mothers to daughters or fathers to sons as helpers with younger siblings within the extended family would now have to be learnt from books, magazine articles, or online videos.

Deprived of the authority, certainty, and confidence which once they derived from a collective consciousness of their rights and duties, parents now find themselves using the method of persuasion, and even attempt to hide their hand behind their duty to protect their children. As Furedi puts it:

Many of the characteristic features of paranoid parenting—using surveillance technology to keep an eye on children, preventing them from participating in outdoor unstructured activities, relying on constant adult supervision—represent forms of control that serve as an alternative to parental discipline. In this way the issue of discipline is displaced and reposed as a question of safety. Parents who feel uncomfortable about refusing yet another piece of chocolate are much more relaxed about imposing their will by preventing their son from playing in the park with his friends. Regulating children’s lives on the grounds of safety is accepted without question as good parenting. Over-reacting to the risks faced by children allows parents to maintain a semblance of control without exercising too much authority. Keeping children under constant adult supervision creates an illusion of retaining control without having to confront the issue of discipline. [p. 146]

Of course, neither Furedi nor I are suggesting that parents are clinically paranoid. On the contrary, I am arguing that their paranoia derives from their deficits in mentalism, not from hyper-mentalism as is the case in clinical paranoia. Indeed, autistic people can become paranoid for the same reason: their deficits in mind-reading lead them to misread others' intentions as more malevolent than they really are and often crystallise around real slights resulting from their own shortcomings in social responsiveness. Actual psychotics, on the other hand, over-interpret the behaviour of others from the start to confirm their paranoid delusions. To make the same point in terms of the previous post: Furedi is saying in effect that, like Don Quixote, modern parents have read more books than is good for them and have been driven mad as a result!

In any event, parental paranoia blends with official psychology's paranoid prejudice against nature as racist, sexist, and homophobic to burden nurture with full responsibility for child development. The result of this has been called the snowflake generation by some critics: children brought up since the turn of the century who are seen to be—and often feel themselves to be—acutely sensitive to environmental insults and influences of all kinds: from unhealthy food to poor parenting or peer pressure. Universities, in particular, have reflected such concerns in their provision of “safe spaces” of refuge for victims; censoring curriculums to remove disturbing material; and curtailing free speech on topics likely to cause offence to anyone. Indeed, even clapped, whistled, or whooped applause was banned at Oxford for fear that such loud noises might damage the mental health of vulnerable students!

Furedi is probably right to advise parents to ignore the experts—at least if we are talking about what I would call official psychology. But there is a scientific psychology of parenting, founded on modern parent-offspring conflict theory and epitomized in the imprinted brain theory. Knowledge of the former would certainly have provided him with a sound, scientific basis for his wholly justified criticism of attachment theory and its ludicrous romanticisation of the mother-child bond; while the latter's insights into development—and particularly into the differing roles of each parent's genes in building their child's brain—opens the door to the neuroscience of parenting.

Admittedly, no one has yet got around to formulating all this as precepts for parents or writing manuals for them based on evolutionary genetics and neuroscience. But all that will come in time, particularly if critics like Furedi continue to blow the whistle on the self-appointed experts and their self-serving official psychology of parenting.