Autism

3 Relationship Strategies for Adults With Autism

How adults with autism can improve their romantic relationships.

Posted February 9, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- There is far less relational support and resources for adults with autism compared to their neurotypical partners.

- Most individuals with autism desire a committed, romantic relationship.

- Common relationship strategies to improve satisfaction should be adapted to accommodate the unique needs of neurodiverse couples.

Neurodiverse couples—particularly those in which one or both partners have been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder—have unique relationship needs. In recent years, there has been a growing number of resources aimed at informing and supporting neurotypical (meaning non-autistic) partners. Yet there is far less support available for partners with autism.

The more we learn about autism, the more it becomes apparent that most adults on the spectrum have a deep desire for the intimacy and connection of a committed relationship (Cheak-Zamora et al., 2019). Unfortunately, romantic relationships are rarely if ever addressed in autism-related services—especially during the critical years in adolescence when these skills are typically developed.

In my clinical practice with neurodiverse couples, I often find that there is an inherent belief—held by both partners—that autism simply is, with no fluctuation or change, and therefore the neurotypical partner must learn to adapt. While it’s important to understand there are indeed autism-related “traits” that are unlikely to change, individuals with autism are absolutely capable of growth and of having fulfilling and meaningful romantic relationships.

Below are three strategies that have been found in research to bolster relationship quality and satisfaction. There are, of course, countless ways in which autism can affect committed relationships; the following strategies have been adapted to accommodate some of the most common needs reported by adults with autism.

1. Reflect, reflect, reflect

Reflection is a communication skill in which the listener highlights the main theme of what someone has shared and then paraphrases it back to the speaker. The main goal of reflection is to convey to the speaker they are being heard and understood.

In my practice, a frequent concern expressed by neurotypical partners is, “You don’t understand what I’m saying.” The partner with autism will often respond with, “Yes, I do. You said…” and proceed to repeat verbatim what the partner just said.

A common characteristic of autism is to receive information in its most basic, literal form. While this trait can be incredibly beneficial in many circumstances, it can be difficult in romantic relationships when there are critical elements of communication that are more subtle.

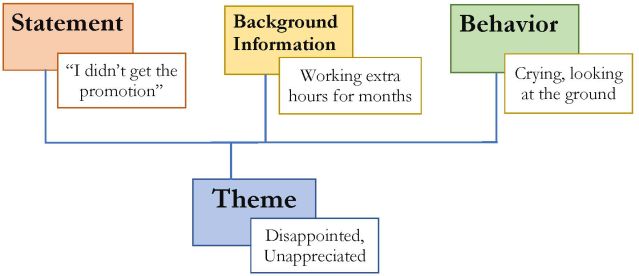

Rather than memorizing and repeating what the speaker has said, the listener should attempt to answer the question, “What does this mean to my partner?” It can be incredibly difficult for those with autism to decipher the internal experience or underlying meaning for others. Below is a figure that can be beneficial for analyzing key pieces of information during the conversation that help to create a reflection.

Imagine, in this example, that you come home from work and your partner is curled up on the couch crying. They tell you that they didn’t get the promotion they’d expected. You know they’ve been working extra hours for months to prove to their boss they could take on the responsibilities of the higher position.

An appropriate reflection, then, may be, “It sounds like you’re disappointed that your supervisor doesn’t recognize your hard work.” The speaker can then share whether that’s accurate or perhaps explain a bit more. Either way, they feel heard, which is the goal of reflection.

2. Connection check-ins

It’s important for couples to maintain thoughtful contact throughout the day; what exactly that looks like, and how frequently it occurs, can vary depending on a couple’s unique needs.

Some people with autism become very successful in their jobs, school, or hobbies specifically because of their ability to become completely engrossed in the task at hand. Yet this quality can also interfere with couples’ ability to stay connected. Individuals on the spectrum may therefore benefit from creating reminders or alarms throughout the day to have “connection check-ins” with their partner at a frequency that seems appropriate (for example, twice a day).

Keep in mind that every moment of contact may not have the same effect on relational connection. Simply exchanging information—like telling a partner what you’d like them to pick up from the grocery store—does not often improve relationship connection. Effective connection check-ins, by contrast, might include in-person conversations, phone calls, or text messages that demonstrate care and concern toward a partner.

General questions like “How is your day so far?” or “How are you feeling?” are thoughtful openers that can help to make connection check-ins more likely to become part of a daily routine. As check-ins become more habitual, more specific and in-depth check-ins—following up on an issue that is on the partner’s mind (for instance “How did that meeting go today?”) or disclosing something personal (“I really enjoyed dinner with you last night”)—serve to keep partners feeling connected.

3. Play together to stay together

Couples that enjoy spending time together and engaging in shared activities tend to have higher relationship satisfaction (Cortes et al., 2020). Yet this can be difficult for some neurodiverse couples because a defining characteristic of autism is a tendency toward restricted interests.

People with autism frequently enjoy interests and activities that are done independently to avoid overstimulation or negative physiological effects (like headaches or sensitivity to light and sound). As a result, neurodiverse couples may have to think creatively to find activities that both partners can participate in without physical discomfort. There may, therefore, also be some emotional discomfort—feelings of anxiety, for instance—when trying something new.

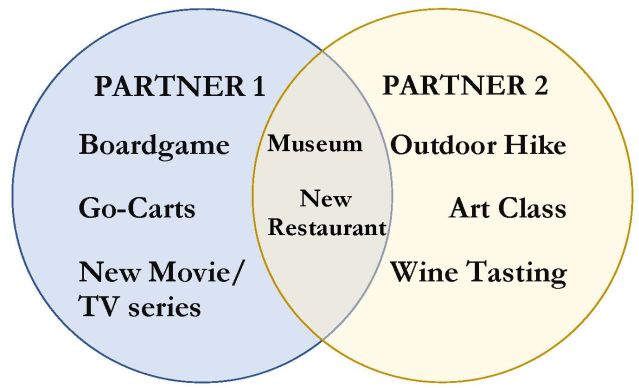

The purpose of shared couple activities is to spend time together engaging in a common activity—not necessarily doing something that both partners love. The diagram below may be used for couples to explore activities that they can both participate in together.

Each partner should independently list a number of activities (for example, at least five activities) they are willing to try together. Both partners should attempt to extend themselves slightly beyond their comfort zone without getting too overwhelmed. Trying new things or visiting new places for both partners is ideal. The couple can then review the lists and determine which activities may have overlap for both partners.

Conclusion

Most of what couples therapists have come to understand about romantic relationships draws on research with neurotypical couples. Reflection, connection check-ins, and shared activities are a few strategies that research shows can improve the quality of romantic relationships.

It is important to remember, however, that modifications or adaptations of many common relationship techniques may be necessary to meet the unique needs of neurodiverse couples. Working with a therapist who specializes in neurodiverse couples can be helpful in exploring the ways in which adults with autism can develop deep and meaningful connections with their romantic partners.

To find a therapist, please visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Parker, M. L. & Mosley, M. (2021). Therapy Outcomes of Neurodiverse Couples: Exploring a Solution-Focused Approach. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 47(4), 962-981.

Cheak-Zamora, N., Teti, M., Maurer-Batjer, A., O’Connor, K., & Randolph, J. (2019). Sexual and relationship interest, knowledge, and experiences among adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48.

Cortes, K., Britton, E., Holmes, J., & Scholer, A. (2020). Our adventures make me feel secure: Novel activities boost relationship satisfaction through felt security. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 89.

Mendes, E. (2015). Marriage and Lasting Relationships with Asperger’s Syndrome. Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London.