Diet

Could Food Cravings Be Withdrawal Symptoms?

The case for a recovery model approach to healthy living.

Posted January 25, 2024 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Many Americans struggle to make healthy nutrition changes.

- Studies increasingly suggest that some foods may provoke withdrawal symptoms, similar to drugs.

- For those facing overeating and withdrawal symptoms, a recovery approach to healthier eating may be helpful.

Sarah's story may sound familiar. For years, she struggled to find a way to improve her nutrition, lose some excess body fat, and feel better. But no matter what healthy or dietitian-recommended Mediterranean, vegetarian, whole food, or low carbohydrate approach she tried, Sarah always ended up feeling worse.

Within hours to days of modifying her regular diet (like many Americans, Sarah's nutrition came mostly from restaurants and ultra-processed foods) Sarah felt tired and sluggish. She'd become moody and irritable. And she was tortured by cravings and ruminations about food. No amount of willpower or motivation was ever enough for Sarah to endure this misery for long. Understandably, she felt discouraged.

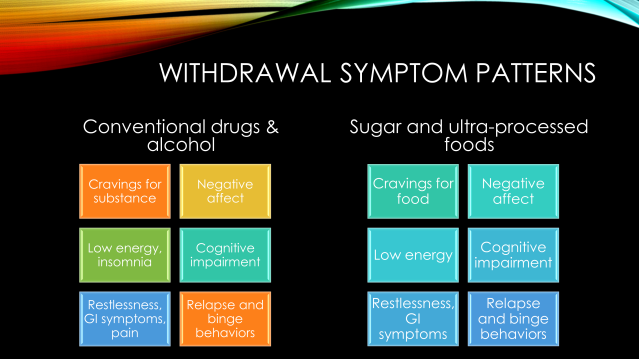

Some timely good fortune helped Sarah's story have a happy ending. A news article she read happened to refer to a 2022 review paper1 discussing the science behind symptoms of something called "food withdrawal"—evaluating the question of whether certain foods could have addictive properties similar to some drugs. What struck Sarah was the information summarized in the image below.

Thinking about the symptoms she experienced when trying to improve her nutrition, Sarah realized they were mostly the same as those mentioned in the review paper describing food withdrawal in humans and other animals. They were also nearly the same symptoms experienced by people withdrawing from substances such as nicotine, alcohol, and other addictive drugs. Had she become "hooked" on an ultra-processed diet?

For the first time, Sarah wondered if she'd been thinking about her health and eating habits the wrong way. Perhaps her nutrition struggles weren't a sign of poor willpower or bad genetics, as she had been telling herself. Perhaps instead her body was simply experiencing a reaction each time she tried to stop eating hyperpalatable foods. The physical and emotional symptoms could be signs of withdrawal, not weakness. The way food seemed to hijack her brain when trying to make healthy changes sounded a lot like some people feel when stopping an addictive substance.

The most powerful insight for Sarah, however, was the new path to improvement this perspective revealed. Based on this food withdrawal model, Sarah realized that she might be able to stop searching for a perfect diet and start thinking about her health and nutrition goals from a recovery perspective. Some key differences between a conventional behavior change plan for improving nutrition and a recovery model approach are summarized in the figure below.

To be clear, whether foods can truly be addictive in the same way that drugs can is still a matter of some debate—and regardless, not everyone struggling with their nutrition is potentially addicted to sugar or ultra-processed foods. Addiction, thankfully, is far from universal, even among people using powerful habit-forming substances such as alcohol, nicotine, and opioids. However, just as there is overwhelming evidence that a subset of drug and alcohol users are vulnerable to becoming dependent on these substances, so too is there growing evidence that some people may develop addiction-like symptoms in response to certain foods.2

For people in this latter subgroup—perhaps like Sarah—the conventional tactics of willpower reliance, overnight dietary modifications, portion control, and calorie tracking are less likely to be successful because of the aversive cravings and withdrawal symptoms they are likely to experience.

Instead, it may be more helpful for people in this subgroup to adopt recovery model tactics proven effective in the treatment of substance use. In a recovery model, for example, treatment is often supported by groups and sponsors rather than left to individual heroics. Behavior changes are more likely to be gradual (e.g., "12-step" approach in Alcoholics Anonymous) rather than made "cold turkey." Recovery models also emphasize attention to mental health, spirituality, and making changes in the social and physical environment to a greater degree than conventional diet and weight loss programs.

Arguably the most important difference between a recovery model and a conventional behavior change program is the emphasis on developing a healthier new identity and embracing life-long efforts to maintain new behavior patterns. If you've ever heard the expression, "There is a cure for addiction. You just have to do it every day," it captures the themes of daily commitment and renewal central to many recovery treatment models.

Even in the absence of a true addiction to drugs or ultra-processed foods, many of us pursuing goals related to nutrition, wellness, and healthy living, would likely benefit from incorporating elements of the recovery model into our treatment plans.

References

1. Parnarouskis L, Leventhal AM, Ferguson SG, Gearhardt AN. Withdrawal: A key consideration in evaluating whether highly processed foods are addictive. Obes Rev. 2022 Nov;23(11):e13507. doi: 10.1111/obr.13507.

2. Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG. Evidence for sugar addiction: behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(1):20-39. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.019.