Psychology

The Psychology of Intermittent Fasting

Success with intermittent fasting comes down to our beliefs about food.

Posted June 3, 2020

Over the past decade, intermittent fasting made the leap from being a popular fad diet to a scientifically supported eating style (1). To put this into context, consider the hundreds of diets that have come and gone over the past few decades in the U.S.; staying power for a diet is rare in the nutrition world.

Even for intermittent fasting, the leap to credibility wasn’t easy. Just 10 years ago, early proponents of intermittent fasting — such as Martin Berkhan and his “leangains” diet – faced an overwhelmingly negative reception among nutrition scientists and most diet and fitness experts. As quality research in both human and non-human animals multiplied during this period, however, suggesting benefits for an impressive number of metabolic, immune system, and even aging parameters, even many initial skeptics began to warm to intermittent fasting as a viable eating style.

In addition to growing scientific credibility (1), intermittent fasting (IF) offers one of the most practical approaches to eating among respected dietary plans, in that:

- IF does not require specific foods or supplements to follow

- IF involves almost no food rules beyond the practice of eating during a reduced time frame, making it about as uncomplicated as possible

- IF decreases time spent cooking, cleaning, and preparing food relative to many other dietary plans by reducing meals generally to 1-2/day

- IF usually reduces grocery expenses, especially when coupled with a focus on eating unprocessed foods

The only major drawbacks to IF are:

- Concerns about hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) among some diabetics

- Hypotension (low blood pressure) side effects from patients fasting while on medications such as antihypertensives

- The risk of exacerbating eating disorder symptoms among people with histories of binge eating, bulimia, and anorexia symptoms

These latter limitations are important and can even be life-threatening in certain cases. For this reason, people with these limitations should consider alternative dietary approaches to IF or use IF only with professional supervision.

Given the combination of health benefits, practicality, and relatively few medical or psychiatric risks, it may not surprise you that IF was among the most popular diets in 2019-2020 reported in surveys in the U.S. and U.K. This popularity, however, is short-lived for many who try to follow one or more of the common IF regimens without success. Because even the healthiest diets can’t help those who aren’t able to practice the diet; it is vital to understand the barriers and solutions to adopting IF for people to consistently experience success.

As it turns out, the barriers to IF are overwhelmingly psychological. This blog post summarizes the psychological barriers to IF in three categories: 1) self-talk; 2) core beliefs; and 3) food rules. For each category, we’ll identify specific thinking patterns that can limit success with IF and specific alternatives that can increase IF success.

1. Self-talk refers to the internal dialogue we notice when we pay attention to our thoughts. Some self-talk is so strong as to manifest in our verbal communication; most self-talk, however, lurks in the background while still affecting our emotions and behavior. Self-talk has a powerful influence on our health and quality of life because it is so frequent and repetitious. It shapes our bodies, minds, and relationships as relentlessly as wind and water can shape a stone.

Figure 1 illustrates some of the most common self-talk examples that undermine how people experience IF, along with improved self-talk alternatives they could adopt to improve their IF experience.

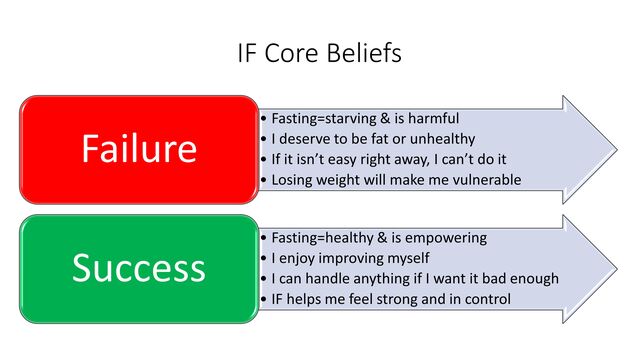

2. Core beliefs refer to deeper, subconscious-level thinking. We have many core beliefs. The most important are core beliefs about ourselves, about other people, and about the world; these latter core beliefs have a profound yet largely invisible influence on the choices we make and the results we obtain in life. Core beliefs are often established in childhood from parents, by early life events, and later by intense adult-age experiences (e.g., traumas). In contrast to self-talk, identifying core beliefs often takes work to recognize (it is a common goal in psychotherapy) and ongoing and deliberate practice to modify. That said, the effort is usually well spent. There are few changes that can so radically alter the quality of our life more than improving our core beliefs.

Figure 2 shows that there are core beliefs about food and eating generally — and IF specifically — that can promote failure with IF no matter what the person’s level of knowledge and motivation. Alternatively, core beliefs that can sharply increase IF success are also presented.

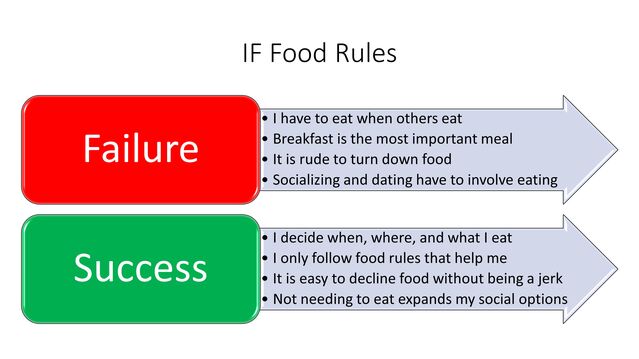

3. Food rules, finally, refer to ideas about food that we have been taught or learned from others. Food rules are inherently neither good nor bad, but are always risky because they promote black-and-white thinking about eating that may be inaccurate. There are more food rules than ever these days and they often conflict. The food rules of a ketogenic or carnivore dieter, for example, contradict those of a vegan or vegetarian, and a person practicing a Mediterranean diet will disagree with both.

Rather than engaging in circular debates about the accuracy of specific food rules, the better approach is to first become aware of the food rules you are already following, and second, to critically evaluate whether these rules are helping or hindering your nutrition goals.

Many of our food rules are simply outdated. Cleaning your plate, for example, is a common food rule that may have served people well as growing children or during the Great Depression while being counterproductive in the present. Other rules may be context-specific or just outright wrong. The point is to stop operating by food rules uncritically and instead begin operating by food rules consciously and strategically.

Figure 3 provides concrete examples of food rules likely to sabotage people implementing IF eating styles and parallel examples of food rules capable of enhancing IF results.

References

de Cabo R, Mattson MP. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease. N Engl J Med. 2019 Dec 26;381(26):2541-2551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1905136.