Bipolar Disorder

The Triumph of Manic Mather

A tale of bipolar disorder from the annals of American history.

Posted March 27, 2018

By Scott Einberger

During the depths of his despair, things seemed bleak for Stephen Tyng Mather. In that classic pose of depression, the wealthy national park enthusiast broke down and cried in front of his closest friends, his hands covering his face. Yet with time and help, the first director of the U.S. National Park Service persevered through his manic depression, and the world is a better place because of this. Although one hundred years separates his lifetime from ours, his story can offer inspiration and ‘food for thought’ for those of us suffering from bipolar disorder, depression, or other mental illnesses today. In three parts, this essay discusses Mather’s beginnings and rise in the world, some of his national park endeavors, and how his bipolar disorder affected him.

Of Borax and Big Mountains

The Mather last name is a big one in New England history. Stephen Mather is a distant relative of Increase Mather and his son Cotton Mather, two influential Puritan ministers of colonial America. The home that Stephen Mather inherited, now known as the Mather Homestead and preserved by the Mather Homestead Foundation, is located in Darien, Connecticut. It too is historical, built during the Revolutionary War by Joseph Mather, a deacon in the church. Yet Stephen Mather himself was raised on the opposite side of the country.

Born in San Francisco on July 4th, 1867, Mather graduated across the bay two decades later at the University of California, Berkeley. Standing just over six feet tall, the blue-eyed, handsome Mather eventually married, had a daughter, and wrote general articles for several years for the Chicago Sun. In the late 1890s, he began working with his father in the borax mining business. Primarily a sales and marketing man, Mather found significant profits in the early 1900s. Along with a business partner, he became one of Chicago’s millionaires and socialites.

During his borax years, Mather also became a conservationist and outdoorsman; his expanding wallet coincided with his increasing interests in nature, mountaineering, and national parks. “Mather was a member—which meant active member—of the Sierra Club of California, the Prairie Club of Chicago, and the American Civic Association,” notes his biographer, Robert Shankland. He scaled the 14,000-foot Mount Rainier in 1905 and also went on trips with his family in what is today known as Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Perhaps symbolically, Mather met and talked with famous environmentalist John Muir during one of these outings.[i]

Whether climbing mountains or promoting borax, the prematurely white-haired Mather was energetic, genuine, friendly, and charismatic. He “was a striking alloy of drive and amiability. He had a horde of interests, and he mixed among them with a zeal that crackled,” writes Shankland. “He was everybody’s friend—a handshaker, backslapper, and ready smiler, but the rare species incapable of fakery. People—people indiscriminately—had his unqualified approval, and he had the unqualified approval of what must have been a record number of them.”[ii] While these characteristics proved beneficial in his writing and then borax work, they were perhaps most important in his third and final career.

Indeed, by late 1914, Mather had grown restless with borax and began itching to do something else with his time and energy. He began quietly observing conservation issues in the national parks, and with friends in high places and connections with UC Berkeley alumni, Mather landed a spot as an assistant to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, focused specifically on national parks. With a hardworking administrator named Horace Albright by his side, it was in the national parks that Mather found his true calling, and in this calling, he did the public good.[iii]

Steve Mather of the National Parks

"Who will gainsay that the parks contain the highest potentialities of national pride, national contentment, and national health? A visit inspires love of country; begets contentment; engenders pride of possession; contains the antidote for national restlessness,” Mather once noted. “He is a better citizen with a keener appreciation of the privilege of living here who has toured the national parks."[iv] With these beliefs as his north star, Mather benefited the National Parks System in several ways in the 1910s and 20s.

First, he successfully lobbied for increased funding for national parks as well as for the establishment of the U.S. National Park Service, the bureau that has overseen the national parks for over 100 years now. In the same social circles with the longtime National Geographic Society president and editor Gilbert Grosvenor, writer Emerson Hough, and U.S. Representative Frederick Gillett of Massachusetts, the ranking member on the Appropriations Committee, Mather brought these and other influential friends and writers on a backcountry trip through the Sequoia National Park area. Known as the Mather Mountain Party, he paid for everything himself, which included fine dining even though they were deep in the backcountry most of the time.[v]

Stephen Mather was known for his high energy, and Grosvenor remembered that every time the group crossed through a cascade or waterfall, Mather would shout, “Here we get a free shower!” He’d then strip down and jump into the snow-fed water while the others either joined him or looked on. He was also the first one up every morning, hollering at everyone else to wake up once the 6:00 am hour hit. On a more serious note though, Mather showcased to his influential friends and associates how the national park was underfunded, how roads and trails allowing visitors into the park were in poor condition, and how ancient Sequoia groves just outside the boundary were vulnerable to logging.[vi]

In the end, Mather’s charisma as well as the superlative scenery won everyone over. Back in the nation’s capital, the individuals that attended the Mather Mountain Party lobbied on behalf of the national parks as well as a new bureau. As a result of this and other similar endeavors of Mather, the National Park Service was established in August 1916, with Mather sworn in as the first director in early 1917.[vii]

A second way that Mather benefitted the national parks is that he used his own pocketbook for the betterment of parks. He helped purchase the Tioga Pass Road, a private toll road, and then gave it to Yosemite National Park in order to have it be a free road for the public. Mather also purchased a sequoia grove for $50,000 and then gave it to Sequoia National Park; donated $15,000 dollars to help start the Save-the-Redwoods League (in a burst of adrenaline while at a public rally, Mather also donated $15,000 of his friend William Kent’s money, much to U.S. representative Kent’s surprise!); and provided ample salaries, bonuses, and vacation money for some of his staff until the government outlawed doing so in 1919. Additionally, he spent $8,000 for a tract of land at the entrance to Montana’s Glacier National Park and then gave it to the government to create a suitable headquarters for the park. Last but not least, he donated ample moneys to the National Geographic Society to conduct scientific research in the newly created Katmai National Monument up in Alaska.[viii]

Aside from helping create the NPS as well as utilizing his own money for park improvements, Mather expanded the National Park System by successfully lobbying for superlative additions. He was instrumental in the establishment of Utah’s Bryce Canyon National Park, Maine’s Acadia National Park, and Arkansas’ Hot Springs National Park, among others. Seeing the incredible power of erosion first hand during his initial visit to Bryce Canyon, Mather was like a kid on Christmas day while exploring the striking geologic formations. Back in Washington, he then moved the necessary political mountains to make it a protected area. The same goes with Hot Springs. Upon visiting the famed Bathhouse Row for the first time with Horace Albright, Mather soon went missing in action. Albright recalled how they first relaxed in the geothermal baths and then went to bed. The next day, Albright could not find his boss for some time. When he searched for Mather in the bathhouses, he found him in a backroom enjoying more hot baths and spa treatments![ix]

Fourth, Mather protected the natural integrity of the national parks while at the same time opening them up for people to enjoy and relax in. He pushed for one major scenic road per park, but no more than one—what is now known as the absolutely spectacular Going-to-the-Sun Road in Montana’s Glacier National Park is a perfect example of this. He also pushed for professional concessioners in the national parks to provide affordable, comfortable lodging and dining options. “Scenery is a hollow enjoyment to a tourist who sets out in the morning after an indigestible breakfast and a fitful nights’ sleep,” Mather once noted. Additionally, he lobbied against resource extraction in the parks, perhaps most notably in arguing against dams at Yellowstone Lake and against a gondola from rim to river at Grand Canyon National Park.[x]

Mather had many more successes than just these four while serving as the interior secretary’s special assistant and then as National Park Service director from 1917 until early 1929. It’s important to note, however, that he did not operate in a vacuum; he was not a one-person team. Sometimes Mather had to largely depend on others for success with the national parks, and probably the best example of this is in 1917.

Mather’s Bipolar Disorder

Indeed, only Mather’s closest confidantes and wife knew about his “nervous episodes.” Almost always depicted as indefatigable and charismatic, Mather struggled throughout his adult life with mental illness in the form of bipolar disorder. One particularly bad bout of this hit him just a few months after the National Park Service had been created and just before he was sworn in as its first director.

During a national parks conference in early 1917, Mather’s mood and mannerisms were quite different than normal. Serving as MC of the meeting, he simply did not appear at several important points, only to reappear more energetic than ever at others, according to Albright. Towards the end of the conference, he became very depressed and negative. Albright had gone home but then was called back by one of Mather’s friends. “I wasn’t prepared for what I saw,” he recalled upon seeing Mather in a small reception room behind closed doors.

He was rocking back and forth, alternately crying, moaning, and hoarsely trying to get something said. I couldn’t understand a thing. He was incoherent. His movements became more agitated while his voice rose. We feared he might hurt himself…Several of us talked quietly to him, trying to soothe his wild mood, but to no avail…Suddenly he broke out…rushed for the door, and, with an anguished cry, proclaimed he couldn’t live any longer feeling as he did. We all understood what he said that time.[xi]

Albright and another friend eventually managed to get Mather to his specialist outside Philadelphia. At the Eastern Pennsylvania State Institution for the Feeble-Minded and Epileptic (later known as the Pennhurst State School and Hospital), he obtained treatment from a Dr. Weisenburg. This included strong doses of sedatives, ample sleep and exercise, and no work. The goal was to keep Mather as calm as possible. And yes, Mather’s arms and legs were probably locked into place at times, as twice the first director of the National Park Service attempted suicide. It was a long process of full recovery.[xii]

After an unknown amount of time in the hospital, Mather’s doctor had him go down to Hot Springs as part of his treatment. A couple of park employees watched over the new director as he enjoyed the rejuvenating powers of hot water and massage. Ultimately it took well over a year for Mather to get back to his normal self during this particular episode of depression, and there were false starts along the way. Faithful administrator Horace Albright took the reigns as acting director during this time.[xiii]

Mather’s “Death Valley lows” with bipolar disorder was not unique to 1917. At minimum, he had a long episode in 1903 as well as in the early 1920s. Work stress and worrying were contributing factors. “It was a tragic story of this brilliant, creative, and successful man who was burdened with a mental condition that could burst upon him, without warning, when fatigue and stress mounted,” Albright notes. “His energy and exuberance, which accomplished so many great things, could turn to deep, silent, suicidal depression with little warning.”[xiv]

Whether Mather talked about his mental illnesses with his friends and family is unknown. What is known though is that similar to the Kennedy brothers’ unfaithfulness to their wives and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s polio, Mather’s mental disability was kept from public view. The Mather Papers at UC Berkeley, home to hundreds of articles written about him both during and directly after his life, state not a single sentence about his bipolar disorder. Albright himself waited until he was in his 90s in the 1980s to write the mental illness memories of his boss down on paper. These factors are part of the reason why Mather is not highly associated with the illness to this day.

But he should be, because Mather ultimately succeeded in life even though he struggled with bipolar disorder. Ever since I have first learned about Mather, he’s been a hero of mine and has fascinated me because of this.

“He was my friend and one of the greatest privileges of my long service in Congress was the opportunity given me to work with him from 1920 until his ill health forced his resignation,” noted conservationist politician Louis C. Cramton shortly after Mather passed away in 1930.

He was a man of the highest ideals, great enthusiasm, generously contributing many thousand dollars annually of his own money in park acquisition and development but always handling Government funds with wise economy…No one knew better the scenic values of the United States than he and no one has done as much as he to raise high the national-park standard…There will never come an end to the good that he has done.[xv]

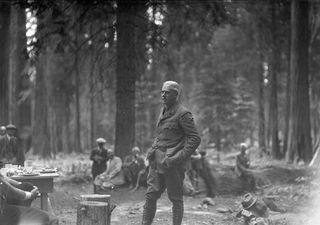

* All photos courtesy of National Park Service.

Scott Einberger is an environmental historian, author, and public lands enthusiast. His books include “A History of Rock Creek Park: Wilderness and Washington, DC,” and “With Distance in His Eyes: The Environmental Life and Legacy of Stewart Udall,” forthcoming in spring 2018 with the University of Nevada Press. Visit www.publiclandslover.weebly.com to learn more about him.

References

[i] Robert Shankland, Steve Mather of the National Parks (New York: Alfred A. Knopf Publishers, 1951), 9; Horace Albright and Marian Albright Schenck, Creating the National Park Service: The Missing Years (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999), 31-32.

[ii] Shankland, 8.

[iii] Albright, 30-40; Robert M. Utley gives Albright great praise in his introduction to the book.

[iv] https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/hisnps/NPSThinking/famousquotes.htm.

[v] Albright, 67-84; Shankland, 68-74.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Richard West Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1997), 41-42; Shankland, 68-83; Albright, 57-84.

[viii] Albright, 38, 99, 211, 273, 301.

[ix] Stephen Tyng Mather Papers, University of California-Berkeley, BANC MSS C-B 535, Volumes 4 and 5; Albright, 115-116.

[x] Mather Papers; Shankland, 211-218.

[xi] Albright, 197.

[xii] Ibid, 199, 202. Albright doesn’t mention the hospital’s name, only that Mather was given treatment at “Devon.” While the Pennhurst hospital building known as “Devon” was actually built after World War II and hence after Mather’s time, Albright wrote his book over 60 years after the events; he perhaps forgot the name of the actual building.

[xiii] Shankland, 165.

[xiv] Albright, 206.

[xv] Congressional Record, March 4, 1931, pg. 6777 and 7126-7127, in Letter to Mrs. Mather by Louis C. Cramton, Mather Papers, Box 4.