Environment

Earth to Humans: Why Have You Forsaken Me? Limited Behavior

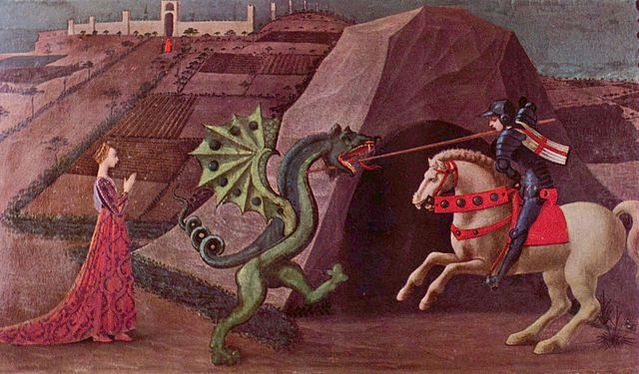

Climate change will keep advancing unless we slay the dragons of inaction.

Posted November 1, 2015

Time to slay the dragons.

Why do we keep failing to respond to severe and growing climate change and other major environmental problems? In previous post, here, I set out to discuss all seven categories of psychological inertia presented by the environmental psychologist Robert Gifford in his article, “The Dragons of Inaction: Psychological Barriers That Limit Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation.”[i]

These dragons of inaction must be SLAIN for us to transition to a healthier, more sustainable world. The seventh and final group of dragons is termed…

Limited Behavior

Are you perhaps doing something to stop or reverse (that is, mitigate) climate change in your own life? If so, you’re not alone. Many of us make at least small efforts to reduce our own personal impacts on the climate: turning up the thermostat in summer or skipping that needless trip to the shopping mall. But one study showed that most of us believe we could be doing more. The final two dragons of inaction sometimes keep people from making the next step to more meaningful changes in their lives.

Tokenism. People who fight off the other dragons of inaction including numbness, discounting, habit, and perceived risk often then make changes in their lives to help protect their community and the rest of the world from the malevolent effects of climate disruption. They might choose any number of actions to participate meaningfully in solutions: flying much less, for instance, or participating in 350.org protests and other actions in their area. But more than likely they’ll choose easier responses such as making a small contribution to an environmental organization or being more conscientious about recycling. The more major change goes by the wayside. In this way “pro-environmental intent” doesn’t necessarily align with pro-environmental impact. The easier, “token” behavioral adjustment may thus serve to block more substantial changes.

Action: Congratulate and thank yourself for responding to climate change, even in minor ways, while many other people do not. You’re doing something good for current and future generations. Let yourself feel good about it, even if your action could be construed as a small token of what needs to be done. BUT then gradually move on to the more serious work mentioned above that you know needs to be done, including educating (and perhaps in some cases even hounding) your political representatives and friends and neighbors to get the legislative and regulatory changes done that stand between our world and a more stable, less climate-disrupted one. Study up on the relationships between climate change and meat, commercial flying, and driving.

![By Lawrencekhoo (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons By Lawrencekhoo (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://cdn.psychologytoday.com/sites/default/files/styles/article-inline-half/public/field_blog_entry_images/JevonsParadoxA.png?itok=RplP14rT)

The Rebound Effect. More pernicious still than tokenism is the rebound effect—the tendency to (fully or partially) erase the benefits of one’s initial mitigations by future choices. A great example is when people buy more fuel efficient vehicles. They then use such vehicles to drive more, justifying their increased consumption by thinking about the greater fuel efficiency they’re getting—a certain twisted pride in consumption. In the process they reduce or even eliminate the benefit of buying the fuel efficient vehicle in the first place. My students often tell me of their parents buying a Prius or other hybrid vehicle and then routinely using its (somewhat) high fuel efficiency as an excuse to go on an extra trip or continue car-commuting to work rather than using public transit. In the latter case, not buying the fuel efficient car in the first place may instead have led to taking the bus to work every day, which quite likely would have resulted in less pollution and climate change overall for that family.

The rebound effect is also called the Jevons Paradox, and has been well known since the 19th century, when its namesake observed that machines that make resource use more efficient, such as improved steam engines, led to further adoption of those technologies and thus greater use of the resource, for example coal.

Action: Rather than taking a single action and then resting on your laurels, remind yourself that truly responding to climate change and other major environmental challenges means making adjustments in all facets of your life. If you’re going to buy a more fuel-efficient car, then also drive less (and thereby make your actions more consistent). Or skip buying the new vehicle altogether and simply choose to use your existing vehicle that much less.

Keep in mind always the mantra of sustainability professionals everywhere: Reduce, Re-use, Recycle. The first term is by far the most important, followed by the second. Reduce all your unnecessary consumption choices. Rather than buying new things, re-use what you have. If you truly have no further use for something and can’t give it to someone else who can re-use it, then recycle it. Keep in mind also the four most important actions in reducing climate change: eat less meat, fly less, drive less, and work with others, including elected representatives, in the hard but fulfilling work of envisioning and then making real a healthier, more sustainable world.

Learn about my book: Invisible Nature

Follow me: Twitter or Facebook

Read more of my posts: The Green Mind

[i] Robert Gifford, “The Dragons of Inaction: Psychological Barriers That Limit Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation,” American Psychologist, May–June 2011, pp. 290–302.