Environment

Despair, Courage, & Hope in an Age of Environmental Turmoil

This may be the most psychologically trying time in all of human history.

Posted November 9, 2013

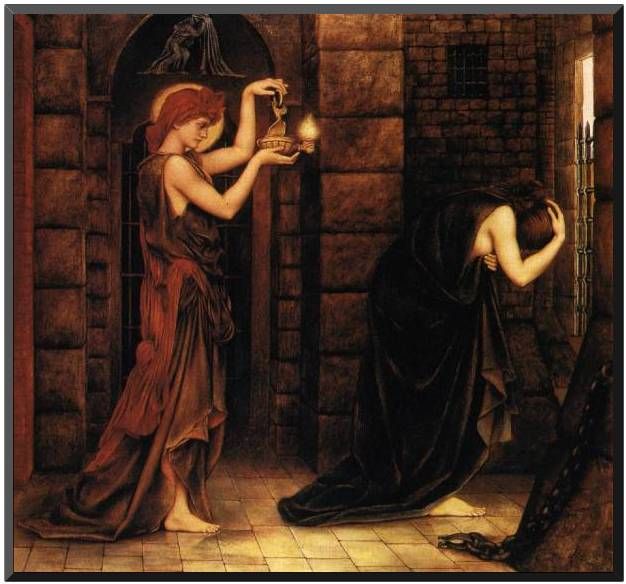

Hope in a Prison of Despair, by Evelyn De Morgan

I recently bought seventeen round-trip plane tickets to bring students from California to Bali for a college course I’m teaching. As a fairly well informed person, and on top of that an environmental scholar, I’m certainly aware that flying is a big contributor to global climate change. And climate change results in all sorts of problems—extreme droughts and heat waves, more intense storms, coastal flooding, lowered agricultural output in some regions, contamination of water supplies via flooding, and so on. The problems are not abstract for the people most directly affected: the organization DARA estimates that as many as four hundred thousand people are killed each year as a result of human-created global climate change.[1] Climate change probably energizes storms such as 2012’s Hurricane Sandy (a.k.a. “Superstorm Sandy”), which resulted in about 150 deaths and $70 billion in damages in North America.[2]

(If you don’t believe global climate change is real or that it’s caused by humans, see below about denial.)

Buying seventeen plane tickets is not a typical day in my life. Rather, it’s an extreme case that highlights the tensions that run through the lives of aware and informed people in our society. Knowing of the harms associated with our flights diminishes my enjoyment of the trip. But I’m hoping that what we learn about human-environment relationships in Bali—and by comparison about those here in the U.S.—will compensate for some of the damages, along with some choices we’ll make to mitigate the harms, such as eating less meat on the trip (meat production contributes to climate change in multiple ways).

Normal damage

I don’t have to buy a lot of plane tickets to harm the environment. Every day, I participate in a modern lifestyle and economy that I know contribute in one way or another to the deepening environmental crises we find ourselves in. I might buy some cookies containing palm oil, much of which comes from plantations in Indonesia where rainforests have been clear-cut to make way for the fruit-bearing palm trees that feed me over here on the other side of the planet (as I discussed in a previous post). Or I flip a light switch, placing a load on the power grid, which, added to other people’s demands, may cause a system operator to fire up a coal-fired power plant, which emits carbon dioxide (driving climate change), sulfur (creating acid rain), and mercury (poisoning the food chain and causing neurological damage to children who may eat mercury-contaminated fish).

Deniability: Oil Palm Concession in Riau, Sumatra

We certainly can make choices that are more aligned with our values. And it feels empowering to do so. I ride my bike around town—about ten times for every one time I drive—and take public transit when I can, thereby reducing greenhouse gas emissions. It’s enjoyable, even when it’s cold and not particularly comfortable, because I know I’m “walking the talk.” I eat no meat because I can’t stand the thought of the suffering of animals in our factory farms and because industrial meat production contributes to various environmental problems.[3]

Doing these things doesn’t make me superior: I know many people who live more ecologically benevolent lives than I, some by choice, some by necessity. It’s fulfilling, though, to follow my own values; it makes me feel better than I otherwise would.

Nevertheless, I don’t want to play a part in the loss of fish habitat by the diversion of a river into my faucet or the contamination of workers’ bodies and landscapes in Silicon Valley or China by buying and using electronics such this computer, as I explain in chapter 1 my book Invisible Nature.[4] But it would be very hard to be a normal modern person without doing things that I know have results I don’t like. And the same is the case for the vast majority of informed people. Indeed, the modern era is unique in that so many of the outcomes of human activity—global environmental crisis in particular—are completely unintended.

Contaminating our Body with Oil Shale Processing

Living in Conflict

If our living conflicts with our values, and if it’s difficult in this society to get the two to truly match up, that should be a major cause for concern. Not only are our environments and physical health at stake, but so is our mental health. When behavior and values conflict, we’re setting ourselves up for angst and despair, and perhaps myriad unknown maladies.

Consider the subjects in Stanley Milgram’s famous obedience experiments, which I discuss in a previous post. They were instructed by a man in a white lab coat to give another person electric shocks by flipping switches, some of which were labeled “DANGER-SEVERE SCHOCK.” Probably none of the subjects wanted to hurt the “learner” in the experiment. The tension played out in various ways. Some subjects quit the experiment. Of those who continued to issue shocks to the screaming learner complaining about his heart trouble, many felt discomfort so extreme that it manifest itself as physical symptoms: sweating, trembling, stuttering, biting their lips, groaning, digging their fingernails into their flesh, and smiling and laughing nervously. Fifteen subjects experienced full-blown, uncontrollable seizures.

If you know that animals are suffering in factory farms because of meat you buy, that people are being killed by the climate change you help create, that forests are falling as you clean the house with paper towels, what kinds of mysterious symptoms might express themselves in your body and mind?

Perhaps foremost among our emotional responses to environmental hazards, loss, and turmoil is despair. The eco-philospher and Buddhist scholar Joanna Macy long ago tapped into the profusion of despair in modern lives in her work around nuclear power and weapons. Throughout human history people have had to live with the knowledge that they would one day die. With the nuclear age suddenly the specter of a far greater death came into consciousness: the possible loss of entire societies and perhaps humanity itself.

Coping with Despair

Despair, sadness, and angst are natural human responses to such overwhelming threats and damages. But these feelings often get sublimated and repressed. They’re unpleasant and difficult. They contradict the positive moral story of linear progress that underlies and propels modern society. They’re so strong that they can interfere with us getting on in our busy daily lives and earning a living. Worst of all, they can thwart action and solutions by overwhelming us and making us feel numb.

A Flood on Java, by Raden Saleh

Joanna Macy’s genius has been to home in on these emotions that often get pushed aside while we focus on daily living. She helps people transform their despair into political action against the destructive forces in our society. After her work in the 1980s unearthing and mobilizing the deep despair and “colossal anguish” arising from the threat of nuclear Armageddon, Macy began to apply similar ideas to concerns about the environment.

With nuclear and other powerful weaponry and growing global environmental crises, we are among the first generations of humans who are no longer certain that future generations will be able to inhabit a safe and healthy planet, Macy observes. Powerful emotions may arise from this knowledge: terror at the possible suffering in store for our loved ones and descendants; rage that we live our lives under an existential threat to humanity that could otherwise be avoided; guilt because our everyday actions—driving, using products made with toxic chemicals—implicate us in this slow-motion catastrophe; and sorrow at the losses already realized and those threatening the future of this beautiful planet.[5]

But these terms are too weak to convey the expanse of feelings that we experience in this context because they originate in concerns about individual persons. Now, we are experiencing the almost unspeakable depths of emotion related to species and planetary catastrophe.

Confronting the Depths

Macy urges us to confront these feelings, to remember the original meaning of compassion—“suffering with.” We shouldn’t pathologize emotional pain arising from these circumstances, as if it’s inappropriate. Pain tells us where we should turn our attention. But we tend to oppress these powerful emotions, so our responses are blunted. Three psychological strategies insulate us emotionally from our environmental pain: disbelief, denial, and the double life, says Macy, in an article titled “Working Through Environmental Despair.”[6]

Disbelief: It’s easy to dismiss the reality of the toxins in air, water, and food or global climate change when the evidence for these problems is not present and visible in our daily lives. Things that disappear—topsoil or birdsong—escape our notice. Problems we can detect with our own senses—smog or plastic trash in the environment—appear so gradually that they become normal parts of life. Such problems hardly achieve a sense of reality for us.

Denial: When it’s hard to actually perceive environmental problems, their existence becomes a matter of debate. Rejection of the problem soothes us and eases the pain. Denial is made easier by the difficulty of understanding many environmental problems due to their complex origins. Because our energy systems are so heavily based on fossil fuels and because all products contain some embedded energy, virtually everything I purchase or use contributes to global climate change. Something that’s everywhere is also nowhere.

In Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life, Kari Marie Norgaard studied Norwegians’ lack of response to climate change. Although Norway is affected by melting glaciers and flooding and the effects are expected to worsen, response has come slow as people push the problem out of their minds to get on with daily life. Norgaard observed how Norwegians in a particular town shaped their social norms and public discourse to create a communal denial of climate change in that prosperous and well educated country.[7]

Manufactured Denial of An Inconvenient Truth

Our lack of direct visceral experience with the effects of climate change and the deep-seated origins of the problem combine to open us up to manipulations that foster more denial. On February 10, 2010, Fox News Channel showed images of US Vice President Al Gore’s book An Inconvenient Truth: The Planetary Emergency of Global Warming and What We Can Do About It planted in a snow bank during a snow storm. Actually, an increase in the number and severity of storms, including snow storms, is one of the expected outcomes of global climate change, so the storm was no proof against climate change—on the contrary it might have been one of its effects.

Double life: Denial gives us the luxury of leading two lives. One is where everything seems OK and we can carry on our daily activities without constantly thinking about the detrimental effects. There, we can remain more or less positive about life. The other life is where we deposit our knowledge of climate change, acid rain, contaminated soils, and species being wiped out every week. That knowledge gets shoved aside as an “unformed awareness” that remains latent in the background, far enough back in our consciousness that it doesn’t interfere with “normal” living.

Macy thinks that repressing knowledge of the damages in this way drains us of the energy that could otherwise be used for clear thinking and action. Some people foreground in their minds environmental problems and begin to act—not only activists but people making changes to their everyday lives to be gentler to Earth.

Anguish into Action

But a larger effort to access “the deep roots of repression” could mobilize great energy in our society to more adequately respond to environmental degradations and nature’s needs. Toward that end, Macy developed the “Five Principles of Empowerment.”[8]

May God help me!, by Bashar Al-Ba'noon Feelings of pain for our world are natural and healthy.

May God help me!, by Bashar Al-Ba'noon

Feelings of pain for our world are natural and healthy.

Pain is morbid only if denied. Disowning our pain makes it dysfunctional, resulting in “numbness and feelings of isolation and impotence.” Repressed pain, Macy believes, makes us seek out scapegoats and turn to depression and self-destruction.

Information alone is not enough. Great quantities of information are available about the state of nature and human societies—far more than any single person can grasp. “Terrifying information about the effects of nuclear pollution or environmental destruction,” writes Macy, “can drive us deeper into denial and feelings of futility, unless we can deal with the responses it arouses in us.” The question is, Can we better integrate this information in our psyches to make appropriate responses more likely? In my book Invisible Nature I show that we must actually witness with our senses, and not merely know about, the consequences of our own actions to be able to respond to them.

Unblocking repressed feelings releases energy and clears the mind. Macy writes, “Repression is physically, mentally, and emotionally expensive; it drains the body, dulls the mind, and muffles emotional responses.” Unblocking our despair can lead to catharsis and release energy in us.

Unblocking our pain for the world reconnects us with the larger web of life. Something more than catharsis takes place when we unblock our distress over the slow destruction of the planet. Our concerns for other people, other species, habitats, the whole living planet, and perhaps the cosmos that lie at the heart of this distress reveal our connections to the greater world. Those connections integrate us into the web of life and the cosmos. As we move through this suffering, we “reach the underlying matrix of our lives,” Macy says. Unblocking these feelings mustn’t be done for the purpose of catharsis alone. Catharsis would then be merely a personal undertaking that pays little heed to the interconnections and larger suffering at the heart of our concerns. As we instead suffer along with the world, we recognize that there is not only pain: “There is also wonder, even joy, as we come home to our mutual belonging—and there is a new kind of power.”[9]

When we recognize our embeddedness in the web of life that extends out into the cosmos, all the way through minerals that enter our bodies and starlight that energizes us, we can then recognize that the suffering of other people and animals and the degradation of all parts of nature are our suffering and our degradation. When we can muster the courage to feel the pain and work through it, we give rise to hope and free up psychic energy to work toward a gentler, healthier world.

Learn about my new book: Invisible Nature: Healing the Destructive Divide between People and the Environment

Follow me on Twitter or Facebook.

Follow my environmental blog: Finding the Human Place in Nature.

Read more of my posts on The Green Mind.

Listen to my recent radio interview with CJ Liu on the subject.

Something to care about, by James Wheeler

[1] DARA and the Climate Vulnerable Forum, “Climate Vulnerability Monitor, 2nd Edition: A Guide to the Cold Calculus of a Hot Planet” (Madrid: DARA International, 2012), pp. 17, 157.

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hurricane_sandy

[3] Michael Pollan and others have documented some of them. See http://michaelpollan.com/articles-archive/power-steer/

[4] Kenneth Worthy, Invisible Nature: Healing the Destructive Divide between People and the Environment (Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 2013).

[5] Joanna Macy, “Working Through Environmental Despair,” in Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind, ed. Theodore Roszak, Mary E. Gomes, and Allen D. Kanner (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1995).

[6] Macy, “Working Through Environmental Despair.”

[7] Kari Marie Norgaard, Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011).

[8] Macy, “Working Through Environmental Despair,” pp. 251–253.

[9] Macy, “Working Through Environmental Despair,” p. 253.