Diet

The "Marrow of Zen" and a Beginner's Mind

The evolution of an obesity narrative

Posted October 28, 2018

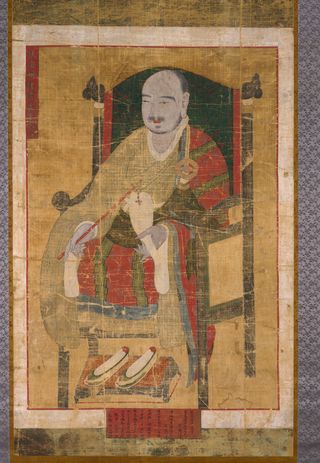

“In the beginner’s mind, there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind, there are few,” wrote Japanese Master Shunryu Suzuki, who brought Zen teachings to America in the early 1960s, in his book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind (1970, p. 1) “A mind should be an empty and ready mind, open to everything,”(p. 2) whereas a mind full of preconceived ideas, subjective intentions, or habits is not open to things as they are,” (p. 77) he explained. For Suzuki, “It is readiness of mind that is wisdom.” (p. 103) He encouraged a “smooth, free-thinking way of observation—without stagnation.” (p. 105) And it is “...under a succession of agreeable or disagreeable situations, you will realize the marrow of Zen.” (p. 24) While essential to any branch of science, this philosophical perspective is particularly applicable to the study of obesity.

It was during Suzuki’s 12 years in San Francisco that he became a Spiritual Master to psychiatrist Albert (Mickey) Stunkard, a renowned pioneer in obesity research, during Stunkard’s time on the West Coast at Stanford. Stunkard wrote of Suzuki’s influence on his own thinking in his paper, aptly entitled “Beginner’s Mind.” (Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 1991) For him, the beginner’s mind meant a particular magic and joy in discovery that allowed his mind to “follow whatever leads seemed most promising” whether or not he knew anything about the subject. This open accessibility led Stunkard to develop creative insights into obesity, particularly in the realm of specific eating disorders and the relationship of obesity to social class and to influences from both nature and nurture, that had not been identified previously and that are still relevant almost 60 years later.

Dean David B. Allison, who writes of the enormous personal impact that Stunkard’s encouragement had early on in his own career development, appreciated Mickey's contagious enthusiasm, humility, “wide-eyed” inquisitiveness, and a genuine willingness to learn from anyone. (Pavella et al, Current Obesity Reports, 2016) In other words, Stunkard was one of those rare charismatic scientists who emphasize the importance of problem-finding, rather than just problem solving, and had that unique ability, not only to achieve excellence themselves, but to evoke excellence in others. (Merton, Science, 1968)

That excellence originates from an ability to shift perspective and develop that free-thinking way of observation. In a particularly original exploration of changing perspectives, Chang and Christakis (Sociology of Health & Illness, 2002) explored the evolving narrative of obesity through the lens of five editions, from its first publication in 1927 to 2000, of the Cecil Textbook of Medicine, “one of the most prominent and widely consulted”medical texts, still in circulation as Goldman-Cecil, with its 25th Edition most recently published in 2016.

In each edition, Chang and Christakis found that authors consistently accepted that obesity results from an imbalance of greater caloric intake than caloric expenditure. What they found, though, is that over the seven decades, the cause of this imbalance shifted “dramatically:” the obese were “initially cast as societal parasites,” but “later transformed into societal victims.” For example, in the 1927 edition, obesity is seen as “aberrant individual activity”—the result of specific behaviors over which the individual had control. By 1967, the focus had now shifted, and obesity had “changed from being the result of something that individuals do, to being the result of something that individuals experience” within a social context: it was society that was seen “as a source of harm,” predominantly from the food industry. By 1985, the chapter's author introduces the disease model of obesity, albeit tentatively. Here, as well, there is an emphasis on both cultural and socioeconomic factors as contributory, while a genetic contribution “may play a role, but its mechanism remains unknown.” Further, the obese now need “sympathetic attention rather than admonition” because of their “multiple failures in weight reduction.”

In the last edition, published in 2000, that Chang and Christakis evaluated, obesity, with a strong emphasis on its genetic roots, is now referred to as a “complex polygenic disease,” but with environmental contributions from the availability of highly palatable foods and decreases in physical activity. This edition also emphasizes the “frustrating condition for patient and physician alike” since the treatment of obesity “is fraught with difficulty and failure.” Further, patients may have a psychological burden resulting from experiencing discrimination. Chang and Christakis summarize, “…we have moved from early models, which invoke the psychological causes of obesity, to contemporary models, which emphasize the psychological consequences of obesity.” They add, “Over the seven decades, (the narrative) changes from one in which the individual is detrimental to society to one in which society is detrimental to the individual.” Importantly, Chang and Christakis emphasize that these explanatory shifts over the years did not follow from any experimental studies.

In expanding on the work of Chang and Christakis, I read the most recent edition, the Goldman-Cecil 25th edition (Jensen, pp. 1458-1466, 2016) The obesity chapter emphasizes the biological: both genetic and now epigenetic contributions are noted, as are the many biological modulators involved in food intake and energy balance. There is also a reference to psychological differences among people with respect to dietary restraint and feelings of hunger. Further, there are sections on secondary causes of weight gain, such as the contribution from medications, and on the multiple potential medical complications (e.g. type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea, cancer) associated with obesity. Obesity is clearly referred to as a “chronic disease” that requires long-term treatment; there is an emphasis that “without approaches to ensure behavioral changes, body fat is invariably regained.” Ironically, the author repeats the popular assumption that a deficit of 500 kcal/day will “theoretically” result in a pound of weight loss per week. (See my blog 99, Mathematical Models: Obesity by the Numbers for a discussion of the so-called 3500 kcal rule.)

In some ways, in this most recent edition, though, the pendulum has swung back to placing more of the onus on the patient and his or her readiness to engage with a physician: “Before a patient enters a weight management program, it is helpful to ensure that the patient is interested and ready to make lifestyle changes and has realistic goals and expectations. Patients who expect to lose large amounts of weight in a short time are virtually doomed to disappointment.” (Jensen, 2016) If patients are not ready, the chapter's author recommends delaying treatment.

More recently, some researchers (Ralston et al, The Lancet, 2018) maintain it is time for a “new obesity narrative.” They acknowledge that an “established narrative” relied on what they consider a “simplistic causal model” that generally blamed individuals for their obesity. Further, this model tended to disregard “all those complex factors for which an individual has no control.” These authors suggest re-framing obesity to include a context for those who have “physiological limitations” from their obesity but exist within the much larger obesogenic environment. “Obesity is not simply about weight or body image. It is about human vulnerability arising from excess fat, the origins of which lie in multiple determinants ranging from molecular genetics to market forces.” (Ralston et al, 2018)

The shifting obesity narratives reinforce the importance of having a willingness to continue learning from anyone, to see possibilities everywhere without preconceived notions, to be a problem-finder. There is a Zen story, a version of which is told by journalist and Zen scholar George Leonard, in the Epilogue to his book Mastery: The Keys to Success and Long-term Fulfilment (pp. 175-76): Jigoro Kana, the man who invented Judo and began the practice of wearing white and black belts in martial arts, was quite old and near death. Calling his students around him, he told them he wanted to be buried in a white belt, the “emblem of a beginner.” Leonard’s explanation is that at the moment of death, we are all beginners, even those who have reached the highest renown and accomplishment. Another interpretation, though, perhaps somewhat more philosophical, is that Kana, eager for knowledge, wanted to wear that white belt as indicative of his wish to continue learning for all of eternity. To wear a white belt humbly, to appreciate that everything, including information we learn, is transient and time-limited and ultimately subject to change, are all qualities of the beginner’s mind and the “marrow of Zen.” “Science,” after all, “issues only interim reports.” (Smith et al, The Benefits of Psychotherapy, 1980, p. 189)