Environment

Democracy and Virtue

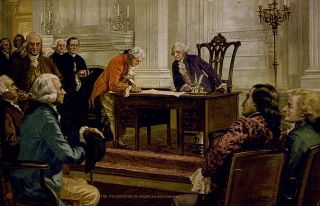

Where James Madison and Niccolo Machiavelli part company

Posted March 22, 2013

The popular reading of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations imagines the Scottish philosopher to be telling the people of his day that they needn’t fret about human selfishness and vice, because Nature, or its Invisible Hand, leads the selfish profit-seeker to serve the general well-being of society in spite of herself. On this view, Smith was taking a stand about the economy that closely paralleled the one his friend David Hume took on government. Hume intoned that “[in] fixing the several checks and controls of the constitution, every man ought to be supposed a knave and to have no other end in all his actions than private interest.” In doing so, he almost seemed to be channeling Niccolo Machiavelli, who wrote more than two centuries earlier that “anyone who would arrange a republic and order its laws must assume that all men are wicked.”

This all sounds very promising for today’s America, where, if there’s one political resource we’re not short of, it’s knaves.

Is it really possible, though, to devise an economic and political system that serves the common good by harnessing the energies of knaves only? James Madison, principal author of both the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, didn’t think so. Though Madison played the central role in devising the system of checks and balances meant to prevent any single competing interest from trumping the others, he apparently did not feel that good government, and a free and prosperous society, could be created by a public and a political elite completely lacking in concern for the common good. “If there be no virtue among us, no form of government can render us secure. To suppose that any form of government will secure liberty or happiness without any virtue in the people is an illusion.” Madison had an even more ancient forerunner in the form of the Roman poet Horace, who wrote that “Laws without morality are useless.”

But where might the virtue supposed necessary by Madison be found, if the caricatured Smith is right that people are thoroughly self-interested? Thankfully, the real Smith surprises the caricaturist on this score. He in fact had written that “How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.“ Even to the capitalist patron saint Smith, human nature included some good. His friend Hume, too, felt that something in human emotional or sentimental nature gave rise to moral feelings.

It’s worth noting that Madison didn’t assert that the American people were entirely virtuous. He merely suggested that there was the hope that there might be some virtue among them. How much virtue is enough?

Economic and game theorists often find, in their theoretical studies, that all that’s needed to sustain an equilibrium in which people act “as if” moral is that enough people believe that enough other people believe that there’s a large enough chance that at least a few people actually have some virtue. If I believe that many others believe that many think that there might be some moral types out and about, and that those other people also believe that it’s better to deal with a moral than with an amoral type when you want to have someone trustworthy on the other end of your dealings, then I’m likely to find that it’s in my own selfish interest to at least act as if I’m trustworthy. I’ll do this so that I’ll have the sort of reputation for trustworthiness that makes other trustworthy people willing to deal with me. Such motives might be enough so that we end up in a world in which most try to act as if trustworthy, with only occasional opportunities to observe who really is and really isn’t so.

With most people appearing to be at least somewhat virtuous and also at least publicly lauding virtuousness in others, a second Smithian trick kicks in, though. “Man naturally desires not only praise, but praiseworthiness; or to be that thing which is the natural and proper object of praise,” wrote Smith. The upshot may be that people not only want to look virtuous to others, they even want to convince themselves that they have some virtue. And with enough of us trying hard enough to seem to have some virtue, the belief that many believe that at least some are really virtuous can turn out to be true (that is, self-fulfilling).

Whether there’s some virtue among us or not seems critical for our chances of maintaining a system of government more like the one Madison had in mind and less like the one Machiavelli assumed. If we want a government that will implement the rule of law, protect public safety and the environment, and so on, as if it were the faithful agent of our society as a whole, then we need at least some virtue in our citizenry, with at least some of us involving ourselves in the monitoring and disciplining of malfeasant public servants. It would help, too, to have a few virtuous public servants who are genuinely motivated to serve the common good and not solely to feather their own nests. Studies of our actually evolved natures, including those by experimental economists discussed in this blog, suggest that these needs are not in fact out of reach.