Trauma

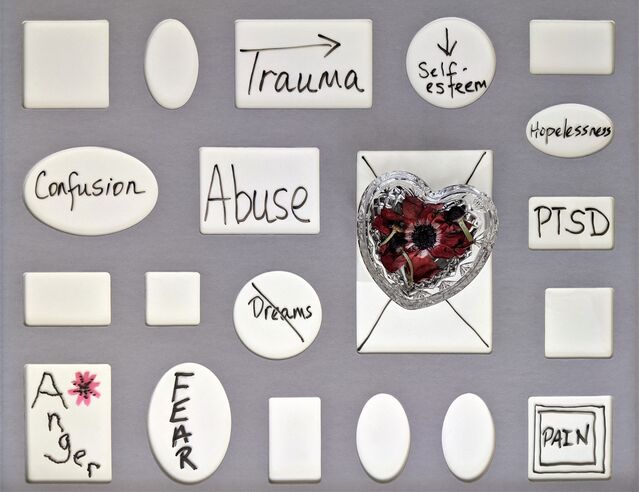

What a Literary Character's Healing Process Might Look Like With CBT

Healing Latimer's trauma.

Posted June 23, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

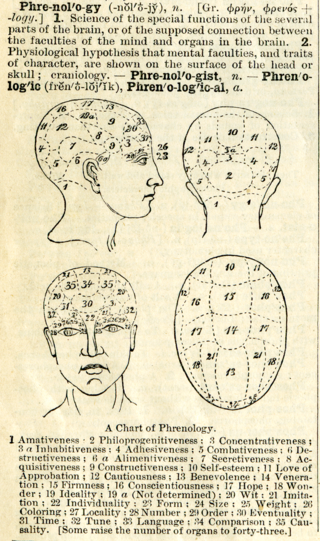

- In The Lifted Veil, George Eliot suggests that phrenology was not a productive diagnostic tool for Latimer's experience of trauma

- In line with Eliot's fictional depiction of dissociation, Janet would have used psychoanalysis, hypnosis, and automatic writing.

- An interview with psychologist Diane Menago helps me to imagine what Latimer's healing process might look like today with CBT.

Part 3 of 3

Part 1 explored how George Eliot’s The Lifted Veil (1859) presents an image of double consciousness akin to dissociation. Part 2 read Eliot’s The Lifted Veil (1859) alongside Pierre Janet’s later works on dissociation (1880s-1920s) to illuminate how Eliot posits an early image of dissociative trauma through Latimer’s psychological experiences.

The Lifted Veil uses supernatural gothic elements to imagine Latimer’s experience of trauma, but the novella does offer one realistic solution: phrenology. Considered a pseudoscience today, phrenology involved the detailed study of the shape and size of the skull as an indication of mental and moral characteristics. Mr. Letherall, the novella’s phrenologist, examines Latimer’s head and deduces that the presence of cranial excesses and deficiencies are the root of his sensitive nature. Dr. Helen Small has used the leading phrenological guide, George Combe’s Elements of Phrenology (1824), to reveal that Latimer’s deficiency around the eyebrow would indicate a lack of order and weak attention to time.(1) His excess at the upper side of his head would suggest an atypical amount of wonder and imagination.(2) In the novella, the treatment was an individualized education plan that would right his imbalances.

Phrenology Misses the Mark

Eliot was initially quite immersed and conversant in this science, but Combe ultimately accused her of losing faith. Together, the characterization of Letherall, the timeline of Eliot’s own changing views, and the strong portrait of Latimer’s trauma prompt readers to think that phrenology misses the mark. If it is not phrenology, what would help Latimer to heal?

Early Trauma Studies

Pierre Janet’s later work on trauma (see Part 2) more closely aligns with George Eliot’s presentation of Latimer’s dissociative episodes. Now commonly referred to as the precursor of contemporary CBT, Janet proposed the use of psychological analysis to uncover subconscious fixed ideas, bring them into consciousness, and reintegrate them to reduce tension and waste of psychic energy. He called this process “Treatment by mental liquidation” in volume 2 of his 1919 Les médications psychologiques.(3) Automatic writing and hypnosis are two of the treatments Janet used with patients. However, Janet detailed how this process might be wrought with difficulty if, once a fixed idea is brought into consciousness, a different pathogenic idea replaced it. Moreover, ultimately, a nonpathogenic idea is needed to replace the pathogenic fixed idea.

Trauma Therapy Today

The DSM-III first included PTSD in 1980, and there are now myriad therapies for trauma: cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), exposure therapy, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and cognitive processing therapy (CPT), to name a few. I spoke with Dr. Diane Menago, a licensed psychologist who specializes in CBT for trauma and PTSD, about how she works with clients who experience depersonalization or derealization episodes due to past trauma. Dr. Menago’s insights can help us to imagine what Latimer’s healing process might look like today.

Imagining Latimer's Healing with CBT

Menago explains how depersonalization and derealization are some of the characteristics of PTSD; they can be helpful coping mechanisms because they help to narrow the scope of affect. Ultimately, Latimer’s episodes would protect him from having to feel the pain of his mother’s loss and any core belief that developed from his trauma. Menago explains that a core belief can be an idea shaped by trauma that affects a person’s self-view and worldview. These core beliefs are often shame-based for people dealing with traumatic experiences. After his mother’s death and his father’s emotional neglect, perhaps Latimer felt abandoned, unloved, and undeserving. Perhaps this past trauma is what ironically motivates his attraction to Bertha, who also avoids and openly scorns him. Experiencing anything that remotely touches this feeling again can overwhelm Latimer, and his emotional stress can escalate. Moving into moments of derealization would protect Latimer from feeling this pain.

For this reason, Menago initially helps clients understand this feeling of dissociation but also to foster gratitude toward it. Rather than cultivating frustration or anger toward these episodes, Latimer would be encouraged to say “thank you” and to appreciate it as that which has allowed him to emotionally survive. Menago stresses that one cannot eliminate these dissociative strategies right away because they have been the cornerstone of a person’s response to trauma. It is the foundation of their house of cards and not respecting that can do more harm than good. She reaffirms that dissociation has been helpful but assures clients that as they learn and develop new strategies they will see this old one fall away.

The work would be to get Latimer back into his body and to connect his mind and his body. Ultimately, Latimer would tell his story and create a trauma timeline. However, doing so might trigger pain and dissociation. There is where mindfulness-based CBT or DBT techniques that address emotional regulation and distress tolerance can be especially effective. Menago coaches her clients in grounding exercises (What do you see? What do you feel? Can you feel your legs against the chair?), breathing, meditation, and body scans to encourage them to be in the moment and to feel. These exercises would help to bring Latimer back to his body.

But so would asking him to physically feel any emotion he names when telling his story. Many clients speak about their trauma as if they were reading off a grocery list, Menago notes. This is protective distancing, a splitting of the mind from the body. If Latimer was telling his story and she saw or sensed a feeling, she might stop and call his awareness to it, asking him to recognize it, feel it, and sit with it. She might encourage Latimer to use any of the mind-body techniques to stay grounded and not dissociate. She might also encourage Latimer to imagine a box kept in her office and to put the story or arising emotion in this box to take an intentional break.

With these techniques, Latimer might be able to slowly create his trauma timeline: the narrated history of his trauma. Menago used a provoking image of experiencing trauma as like living with a bag of broken glass within oneself. It perpetually jabs from within even if, or perhaps because, it is not acknowledged. To slowly pull these jagged pieces out and lay them down in a, albeit still-cracked, puzzle can be healing. Once Latimer retold his story and his jagged puzzle was out before his eyes, he could look at it from a different perspective, begin to challenge his core beliefs and reframe the way he thinks about his trauma. Is he indeed unworthy, unlovable, unloved? Through this work, Latimer could, –to use Menago’s metaphor, begin to slowly raise the blinds to let in more emotional and physical experiences in his life: not just the bad but also the good. He could begin to heal.

References

Eliot, George. The Lifted Veil; and, Brother Jacob. Edited by Helen Small, Oxford University Press, 2009.

Janet, Pierre. Psychological Healing: A Historical and Clinical Study. Edited by Paul Eden and Paul Cedar. New York: MacMillan Company, 1925.

Menago, Diane. Interview. Conducted by Melissa Rampelli, 16 June, 2022.

Small, Helen. “Explanatory Notes.” The Lifted Veil and Brother Jacob, edited by Helen Small, Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 88-104.