Autism

Fiction and the Verbal Cinema of Emotion

An English professor collaborates with autistic readers.

Posted November 7, 2018

In his new book See It Feelingly: Classic Novels, Autistic Readers, and the Schooling of a No-Good English Professor, Ralph James Savarese chronicles his collaborations with several autistic readers, exploring classic American fiction. I was riveted by Savarese's book—both the elegant writing and the procession of deeply humane insights. So I was delighted when he agreed to an interview, on topics ranging from literature's transformative capacities, getting schooled by Temple Grandin, autism research, and Moby-Dick.

In See It Feelingly, you tell the story of your work reading classic American novels with autistic readers across the spectrum. Your collaborators all bring distinct neurological experience to their reading—and dispel some myths about autism in the process. How did you come up with the idea for the book? What were some of your hopes when you began?

My son, DJ, is autistic. From the moment he learned to read, I read works of literature with him, especially poetry, which he loved. In almost every respect but the most basic or obvious ones, he defied the traditional understanding of autism, which speaks of impairments in social communication, interaction, and imagination. Such impairments would render the reading of literature a less than promising endeavor, as literature depends on things like figurative language and complex theory-of-mind—things that autistics are said to be bad at. As I met more and more autistic people, I saw that they, too, defied this description of their difference. They were dynamic and particular; the DSM, static and general. Because I am a literature professor and because my own experience had taught me otherwise, I just dispensed with the notion that autistic gifts were strictly logical or mathematical.

After reading The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn with DJ—it was the key text in his junior-year American literature course—I wrote a piece called “River of Words, Raft of Our Conjoined Neurologies,” which reflected on the concept of readerly identification. (This piece would become the book’s prologue.) At first, DJ identified intensely with Huck who was also beaten by a birth parent and later adopted. "Pap got too handy with his hick'ry, and I couldn't stand it. I was all over welts," Huck tells us at the beginning of the novel. Then DJ identified with Jim and the quest for freedom. Finally, as someone who doesn’t speak, he identified with the lonesome and meandering Mississippi, which functions like a central, if undeclared, character. The river’s melancholy intelligence seemed akin, DJ said, to that of a nonspeaking autist: Both remain unrecognized. Each of these acts of identification brimmed with emotion. Around this time, I started reading works of literature with other autistic people, and the idea for the book was born.

My hopes were two-fold. First, that I could push back against a noxious stereotype, which deprives autistics of their full humanity and which often tracks autistic students out of language arts classes. (If they are included in regular education, it is usually in math and science.) Second, that I could demonstrate the power of literature—its transformative effects—by profiling a group of marginalized, yet deeply invested, readers. See It Feelingly is a work of nonfiction; it’s not a traditional scholarly monograph. In other words, it’s readable!

What do you hope autism researchers might learn from your work?

I’d like them to think seriously about the value of collaboration. I had no interest in testing autistic people, no interest in declaring anyone deficient. Rather, I sought to learn from, and with, my book’s subjects. And I sought to do so over an extended period of time. I didn’t just bop in and read a book in a week and think—haughtily—that I had gathered reliable information. I spent months, and in some cases years, reading with my collaborators. Why is this important? Autistic performance can be uneven from day to day, even hour to hour. I wanted “to control,” as scientists like to say, for this fact. In addition, I wanted to give myself a chance to correct my own misperceptions. Only time, deep immersion, and feedback from my collaborators would let me do so.

I’d also like researchers to think more about autistic diversity—and not simply in terms of “severity” or “functioning.” As Ian Hacking has pointed out, the spectrum trope is entirely too linear. The six readers in my book couldn’t be more different from one another. We need to conceive of autistic diversity as robust, staggeringly robust; we need to be careful with generalizations.

What are some of the novels you read? How did you choose them?

In addition to Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, I read Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Carson McCullers’s The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, and two short stories from an anthology titled Among Animals: The Lives of Animals and Humans in Contemporary Short Fiction. I read the stories with Temple Grandin because she didn’t have as much time as my other collaborators to devote to the project. Oliver Sacks had once suggested that she was uninterested in literature, so I purposefully chose stories involving animals to see if that would make a difference. (Spoiler: the animals were unnecessary: she loved talking about literature. In fact, she alluded to Dante and recited lines by Wordsworth from memory.) One of my collaborators was both autistic and deaf; for her I chose the McCullers novel because it features a deaf protagonist. Another had minored in Native American Studies in college; for him I chose the Silko novel. With Melville, I simply wanted to re-read this book. That it involves a hunt seemed relevant, but only after discussing Moby Dick did I learn why. Dick’s novel also involves a hunt, and it hinges on the question of whether or not the replicants, who are said to lack empathy, are really less human than the empathy-challenged humans who stalk them. For years, of course, scientists have claimed that autistics lack empathy.

Temple Grandin surprised you. She mentioned that nobody had ever asked her about literature, but that she’d loved her Western Civilization course in college. The surprise leads you to some reflection on your own “narrow” expectations. What preconceptions did you bring to your work with Grandin? How did those change?

I call the chapter about Temple “Take for Grandin” in order to stress how stereotypes about her (and about autism in general) cloud our thinking. This “no-good English professor” made all sorts of mistakes. I had forgotten that Temple had enjoyed an undergraduate liberal arts education. I had assumed that a story would need animals for her to be interested in it or, at the very least, for her to be able to demonstrate her interpretive abilities and to respond with emotion. I had also assumed the need to respond with emotion. I had retained, in other words, a normative sense of literary response: one must be moved in order to count as an authentic reader. How could I invest in the concept of neurodiversity while secretly privileging a particular kind of response, namely my own?

At the same time, I believed in both literature’s transformative effects and the doctrine of “presuming competence” when encountering cognitive disability. I knew of studies that showed how reading literary fiction can elicit emotion from “individuals who were habitually avoidant in their attachment style, and who usually reported diminished emotionality.” Can one be competent and different at the same time? The short answer is “yes.” The long one is more interesting and paradoxical. By the way, Temple, who describes herself as unemotional, did respond with significant emotion to the second story, but I don’t want to give too much away. The other autistic readers in the book do not struggle with feeling or recognizing emotions.

What’s the origin of the title See It Feelingly?

The line comes from King Lear. The Earl of Gloucester, whose eyes have been gouged out, begs to be led to the cliffs of Dover so that he may jump off and kill himself. While on the heath, he runs into Lear who foolishly bequeathed his kingdom to his conniving daughters and has himself plunged into madness. As Lear decries the failure of ordinary sight to uncover ruthless deception, Gloucester invokes a different—and, in the end, superior—kind of vision. “Your eyes are in/a heavy case, your purse in a light; and yet you see how/this world goes,” the King says. “I see it feelingly,” Gloucester replies.

I use this line to suggest the nature of literature's hold on us. When we read a novel, as scientists and cognitive literary scholars have demonstrated, we "see it feelingly." We produce, that is, sensuous mental imagery in our heads: visual imagery, auditory imagery, tactile imagery, motor imagery--even, for some of us, olfactory and gustatory imagery. And this imagery is bathed in emotion. As the great Italian neuroscientist Vittorio Gallese has written, “Visual imagery is somehow equivalent to…an actual visual experience, and motor imagery is also somehow equivalent to…an actual motor experience.” You might even think of literature as a verbal cinema of emotion, a kind of old-fashioned movie house in which neither a projector nor a screen is necessary. It's all internal. In the introduction to See It Feelingly, I note that Temple Grandin’s famous phrase “Thinking in Pictures"—it’s the title of one of her books—lines up nicely with what literature asks us to do.

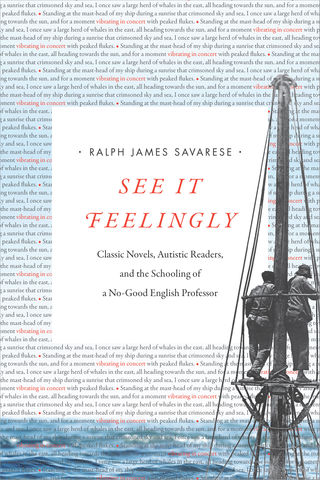

The cover of this book is gorgeous. It’s lively and a little mysterious. It feels like there’s a story there. How did the cover come to be?

The cover image shows two African American masthead watchmen aboard the whaleship Daisy in 1912 (courtesy of the Whaling Museum and Education Center at Cold Spring Harbor, in Long Island, NY). They are looking for whales. I asked for the cover to show these two watchmen. Courtney Baker, one of Duke’s wonderful book designers, suggested the ghosted text from Moby-Dick. To me the cover evokes the position of the reader who “vibrates n concert” with what she reads. When immersed in literary fiction, we are high above the decks on the masthead of our sensory imaginations.