Happiness

Does More Money Make You Happier?

Recent research demonstrates some surprising links between income and happiness

Posted March 8, 2013

It’s somewhat embarrassing for me to admit this, but as a child, my family’s WorldBook Encyclopedia’s “M” book opened directly to the article about money. As an 8-year-old, I was fascinated by all the different bills that existed and the perceived happiness they would one day bring me (spoiler alert: the $100,000 bill that I so longed for is no longer in circulation). Although my obsession was admittedly a little weird, I think it’s safe to say that I’m not the only person who has thought about money and happiness before. The two topics, in fact, have quite a few websites associated with them: a quick google search revealed that “money” clocks in at 3 billion hits and “happy” at 2.9 billion. (People still seem to be fairly idealistic, though, as “love” garnered 7.8 billion hits).

But, what’s the link between how much money people have and how happy they are? In the 1970s, Richard Easterlin published a highly influential paper suggesting that, contrary to what most people might have imagined, there was no relationship between absolute income and well-being. Richer countries, in other words, did not necessarily have citizens who had a higher level of subjective well-being. Within a given country, however, the expected relationship arose: richer people were happier than poorer people. Easterlin’s conclusion was that relative income is crucial for well-being. You’ll be much more satisfied if you have an income of $50,000 in a country where the median income is $25,000, than if you have the same income in a country where the median income is $100,000. So, that’s two major findings: 1) between countries, there is no relationship between well-being and income and 2) within countries, there is a very strong relationship between the two.

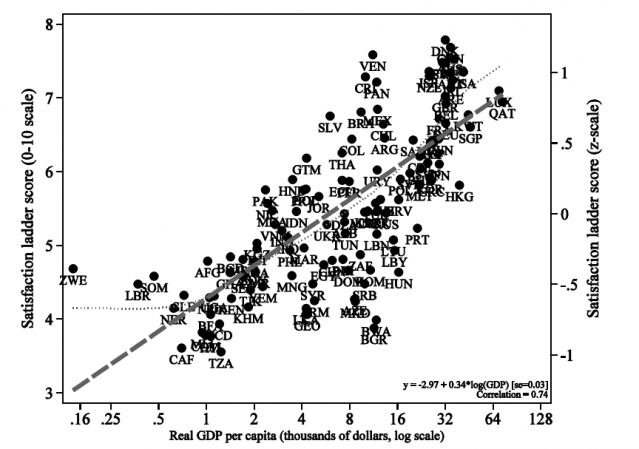

Recent work by the economists Justin Wolfers and Betsy Stevenson, however, has challenged these findings. Unlike the original Easterlin paper, in a series of articles, Wolfers and Stevenson find quite a bit of evidence for an effect of absolute income on well-being. A figure that they created neatly sums up eleven words: richer nations have citizens who are more satisfied with their lives.

Moreover, in their surveys, they fail to find evidence for Easterlin’s second major finding that there is a bigger within-country relationship between income and well-being than a between-country relationship. In fact, in 25 countries that they surveyed, Stevenson and Wolfers find that, numerically, the well-being--income link is just as strong within a given country as it is across countries.

Why would one set of papers so wildly contradict the finding from an earlier one? There’s one major reason. When Easterlin set out to answer the well-being--income question, way less cross-national data was available then than is obtainable now. For the limited sample that Easterlin was working with, his conclusions bore out. But, when that sample was expanded to include dozens of datasets, hundreds of countries, and millions of observations, a different story emerged.

The new results don’t necessarily mean that Easterlin’s conclusions should be rejected outright. Consider that the datasets analyzed in the above papers didn’t look at “happiness” per se, but rather looked at how satisfied people were with their lives, which is just one way of indexing well-being. Typically, the question that was asked of participants went something like this: “Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom to ten at the top. Suppose we say that the top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you, and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?” There are also other ways to measure well-being, however. Ed Diener and Daniel Kahneman, two pioneers of well-being research, note that you can also ask people about “experienced happiness,” which is defined by measures of positive and negative affect (for example, “how happy were you yesterday?”). Because both Diener and Kahneman are senior scientists with the Gallup Organization, they were able to ask variants of these two different ways of measuring well-being (that is, the “ladder” questions and the “happiness” questions) in the World Poll, a huge multi-national study of people’s attitudes and feelings.

When you look at the questions about people’s overall life evaluations (the ladder questions), the data show that there is in fact a strong relationship between income and life evaluations across countries. In other words, just like the Wolfers and Stevenson findings, richer countries have people who are more satisfied with their lives.

A different picture, however, emerges when positive and negative emotion are examined (rather than life satisfaction). Here, Diener and Kahneman show that the correlation between income and “affect balance” is much weaker across countries. Furthermore, in line with Easterlin’s original findings, within a given country, people who have higher incomes also experience more positive emotions and fewer negative emotions.

Richer countries, then, do not necessarily have citizens who are “happier,” but they do have citizens who are more satisfied with their lives. This finding may sound strange, but it makes sense when you consider the variety of factors that lead to happiness. Diener and colleagues found, for example, that learning new things and having a strong social network were good predictors of feelings (like happiness). Positive feelings, like happiness, may be slightly influenced by income, but are more influenced by things like general temperament, the people you spend time with, and the types of activities that you do.

So, does money matter? Yes, but it depends on what you mean by “matter.” You may be more satisfied with your life if you have more money, but this doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll be happier. Happiness and satisfaction are simply different things. Being in the upper echelon of the income distribution won’t necessarily put you in the upper echelon of the happiness distribution. But engaging in meaningful activities and surrounding yourself with engaging friends might go a long way toward getting you there.