Suicide

The VA Releases Second National Suicide Data Report

Why using "22 veteran suicides a day" is inaccurate and potentially harmful.

Posted August 28, 2018

This summer the Department of Veterans Affairs released its second VA National Suicide Data Report. This report, again representing a joint effort between the VA, analysts, and researchers, assesses suicide data from 2005 to 2015. Its predecessor, released in 2012, gave rise to the widely held belief that 22 veterans a day die by suicide. This report adjusts that figure by two, establishing a number closer to 20 a day--a number which has reportedly remained constant from 2008-2015. Moreover, the report states that this number also includes active duty service members, National Guard, and Reservists.

This report farther breaks down that number into those using VA-provided care (six per day), Veterans not utilizing VA services (11 a day), and those currently on active duty, National Guard, and/or in the Reserves (four a day). Perhaps, most importantly, it contains information on ethnicity, era of service, and age group comparisons.

The result is a refutation of the current belief that younger veterans, or those of the Global War on Terror generation (post-9/11 veterans), account for the bulk of veteran suicides. In fact, veterans who served during peacetime (i.e. the years between major conflicts) account for one-third of deaths by suicide in 2015.

While rates of suicide were highest among younger veterans (ages 18–34) and lowest among older veterans (ages 55 and older), veterans ages 55 and older accounted for 58.1 percent of all veteran suicide deaths in 2015. [Suicide rate: A suicide rate divides the number of suicide deaths by the relevant population size for a period of time.]

With veterans over the age of 50 accounting for 73 percent of the entire veteran population, it makes numerical sense they account for the majority of veteran death by suicides. From a phenomenological perspective it also fits, as the bulk of suicides in America are overwhelmingly middle-aged men.

The higher suicide rate among younger service members and veterans (age 18-34) is concerning and harder to understand. A commonly used key demographic bracket (18-34) in research, the belief is that those that fall within that cohort share similar experiences or characteristics. However, for anyone that has spent time in the military, the experience of an 18 year old on his or her first tour of duty is vastly different from a 32 year old, non-commissioned officer, with multiple deployments who has transitioned out. Unfortunately, the report does not shed more light on where the burden is most significant in that population.

As with the previous report, the data must be interpreted with caution. The current report is beset by some reporting inaccuracies—in particular, differing and competing institutional definitions of "veteran." The result is potentially either an under- or over-reporting of death by suicide, dependent upon the applied definition. However, the VA and Department of Defense are working together to better align reporting processes. The VA has stated they will provide an additional report with data from 2016, in the coming months.

When the first report was released in 2012, many people, in a well-meaning effort to call attention to something alarming, miscarried the application of the 22-a-day narrative. This number now dominates social media and has been adopted by a number of Veteran Service Organizations.

The failure to contextualize that figure, or any figure, results in a narrow focus on the number itself with a blind eye toward both its complexity and limitations. Emphasis on the sum of the parts and not the parts themselves, can stagnate, change, and prevent other relevant findings–potentially better positioned to inform policy–from coming to the forefront and effecting change.

For example, combat veterans have a slightly lower suicide rate than those who have never deployed. That statement alone highlights the convolution and magnitude of the issue. America has never before engaged in so long a conflict and with an all-volunteer force. Much like previous generations of veterans, this latest generation is not unique in its uniqueness and before we can help, we must understand.

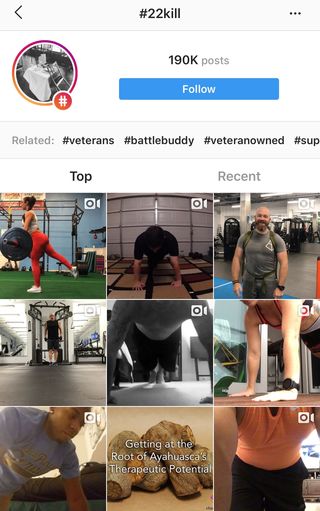

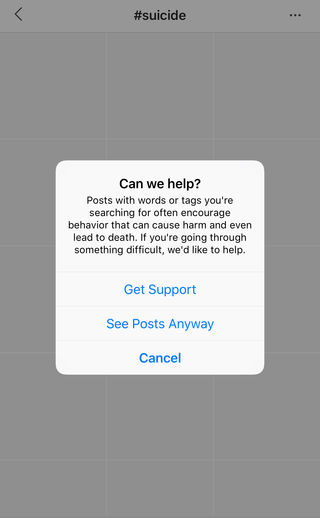

So outside of the obvious pitfalls of using an inaccurate number to capture a phenomenon that may not actually be a phenomenon across time and space, it is also worth considering that the continued emphasis on awareness and attention to veteran suicide may be contributing to it. A cursory search of the hashtag #22aday or #22kill nets hundreds of thousands of results. The most recent posting? Three hours ago, with the top results being videos of people doing push-ups to raise awareness. Even more disheartening, if you are to search the hashtag #suicide, a pop-up appears with a warning and offer of help.

Social media can be a powerful tool for saving lives, advocacy, and suicide prevention and it may be a double-edged sword. With more social media use correlated with more depression, there is very real risk that veterans might feel they are not living up to their former lives, lives of their former teammates/buddies still in the fight, or the general idealized portraits that people tend to portray. Moreover, the intense focus on suicide itself may cause veterans to view themselves and others as more vulnerable than they actually are.

Furthermore, there is a strong body of evidence to suggest that suicide is contagious. People who complete suicide are already vulnerable for a whole host of reasons, and publicity around another suicide appears to make a difference. This suggests that one death can set off others.

Discussing military and veteran suicide within the military and veteran population is fraught with challenge, for both the reason above and many others. A highly charged, emotional issue, many feel strongly that the current statistics are not an accurate representation of what is actually occurring in the community, believing intently that Iraq and Afghanistan veterans are killing themselves at unprecedented rates—regardless of the fact the data shows that suicide rates for Iraq and Afghanistan veterans receiving care at VA facilities are not that different from patients of other wars.

While researchers and mental health professionals may be missing pieces of the puzzle, we can all act to combat the existing narrative and drive dialogue around military and veteran suicide. The 22-a-day belief is damaging and contributes to the "broken vet" stereotype. With Americans believing that more than half of veterans have mental health problems, there remains a need for de-stigmatization while also confronting false ideas and misleading discourse.

Too many organizations have concentrated on awareness without knowing how to translate that awareness into action. Awareness does little as it infrequently gets people to change their behavior or act on their beliefs. When done wrong, an awareness campaign carries risk, including doing more harm.

Personal efforts made to provide information to veteran businesses referring to and using "22 a day," have been met with astonishing responses. From “it’s recognizable,” to “its part of our brand,” to changing it “will detract from our message,” are all actual conversations I’ve had. It seems possible that the monetization and adoption of an incorrect suicide statistic for gain, whether it’s "likes," dollars, attention, or appealing to donors, is happening.

Suicide is a problem in the United States; it is on the rise for both veteran and non-veteran populations and it is hard for anyone to say with certainty who might fall victim to suicide, unless they’ve already been identified as high-risk. There is no easy solution but for starters, a moratorium on the 22-a-day hashtag activism and “awareness” campaign is long overdue. If overhauling "22 a day" is that impossible or unlikely, perhaps petitioning Facebook for the same pop-up box mentioned above is a practical place to begin.

Now, more than ever, we have a better understanding of risk factors associated with suicide and best practices for effective intervention. It is still not fool-proof or comprehensive, but there is a "growing consensus that insomnia, agitation, and social withdrawal are warning signs of an imminent suicide." While not as catchy as a well-rounded number or as appealing as a push-up campaign, it is empirically derived.

**If you’re a Veteran in crisis or concerned about one, there are caring, qualified VA responders standing by to help 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Call 1-800-273-8255 and Press 1

The Veterans Crisis Line is a free, anonymous, confidential resource that’s available to anyone, even if you’re not registered with VA or enrolled in VA health care.

What to Expect:

A trained responder will answer your call. The responder will ask you a few questions, such as whether you or the Veteran or Service member you’re concerned about may be in immediate danger or at risk for suicide. You will decide what to share about yourself and what you want to talk about. Learn more.

The Veterans Crisis Line is also available by text or online chat:

- Chat

- Text 838255

- Support for deaf and hard of hearing: 1-800-799-4889

References

McCall, W. V., & Black, C. G. (2013). The Link between Suicide and Insomnia: Theoretical Mechanisms. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15(9), 389. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-013-0389-9

VA National Suicide Data Report. (2018) https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/OMHSP_National_Suicide…