Relationships

Joanna Harcourt-Smith On Love, History, Memory and Truth

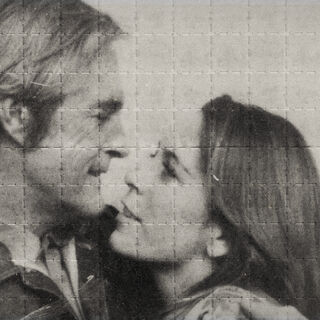

New documentary explores a fascinating woman's love story with Timothy Leary.

Posted December 2, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.” This well-known adage by Kierkegaard came to mind as I watched My Psychedelic Love Story, the latest film from academy-award winning documentarian Errol Morris (The Fog of War, The Thin Blue Line, Tabloid, to name only a few).

Though the film is sure to gravitate to history buffs of the psychedelic movement and to fans of Morris’s signature documentary style, I found this particular work touches on so many of the values of talk therapy in sifting through confusing experiences and personal trauma. In several ways, I think his film embodies the value of introspection and remembering to foster personal growth and acceptance.

The film takes its title from the subtitle of the 2013 memoir, Tripping the Bardo with Timothy Leary: My Psychedelic Love Story. Its author, Joanna Harcourt-Smith, is the only person interviewed in the film. Does this make the film a visual retelling of her book? Yes and no. Is the film about Timothy Leary and his historical significance? Yes and no. Is the film a new exploration of what Joanna Harcourt-Smith left out of her book? Yes, and no, and so much more. Yes, in that the film is her highly personal account. No, in that there is overlap and even contradictory information to what she wrote. So much more, in that the more personal any story becomes, the more universally it speaks to the lived experiences of others, and this film is most concerned with the deepest of personal truths.

Not only is Harcourt-Smith a magnetic storyteller, her story itself speaks to the spirit of 1970s' counterculture, having not only been Timothy Leary’s confidant and muse but a wealthy and rebellious heiress connected to some of the most lauded artists of the time, from Salvador Dali and Andy Warhol to William S. Burroughs and Keith Richards. It’s easy to see why Morris chose to focus his lens and the film on her. “The swath that she cuts through the world of pop music, celebrity, art, and privilege in the '70s makes her very much a woman of that time,” said Morris.

Morris’s interview with Harcourt-Smith reexamines the chaotic five years she spent with Timothy Leary, the Harvard professor, psychologist and author who famously espoused the widespread use of psychedelic drugs. To many, including Harcourt-Smith, mysteries continue to surround the time of Leary’s exile, re-imprisonment and subsequent cooperation with the authorities as an informant, but this is only a small part of the journey we are taken on as the audience. The real journey we witness is the one between storyteller and listener, one that feels in Harcourt-Smith’s telling, like she herself is discovering more about her own story as she remembers and shares it. At these moments of self-revelation, I was mentally transported to some of the moments in my own life, whether in a therapist’s office, talking to a friend, or journaling, when epiphanies have emerged from well-trodden emotional soil like gold.

“There is an element of wanting to tell a story to another person that makes it come alive,” said Morris. The viewer can see this process as it works through Harcourt-Smith. It’s at times when she is recalling the most painful experiences in her life, a childhood sexual trauma, her fraught relationship with her emotionally distant mother, struggles with substance abuse, when she looks so deeply into the camera lens, it feels as if she were looking me directly in the eye, willing to confront her choices and explore what they mean in a new way, even in the late stages of life. “Joanna saw herself as a mystery. Maybe we all are ciphers to ourselves,” Morris said, “and through talking and trying to understand ourselves we come to grips with who we are. She was open to all kinds of experiences all the way up to her death. It’s a compelling way to live one’s life.” Joanna Harcourt-Smith was able to see the film before she passed away earlier this year after a long illness. During my interview with him, Morris told me that at her funeral he said, “To know Joanna was to love her.”

I thought about the film’s title. Does the “my” in My Psychedelic Love Story point to Harcourt-Smith’s memoir and experiences? Yes, but so much more. Could the “my” refer to the filmmaker, his documentary a loving homage to the life of a fascinating woman he came to so admire? Quite possibly yes. Could it be a metaphor for the many kinds of mysterious stories, love and otherwise, that we return to, retell and ponder over and over, searching for a greater understanding of our lives and ourselves? I’d like to think it is all three.

My Psychedelic Love Story is available on SHOWTIME now.