Intelligence

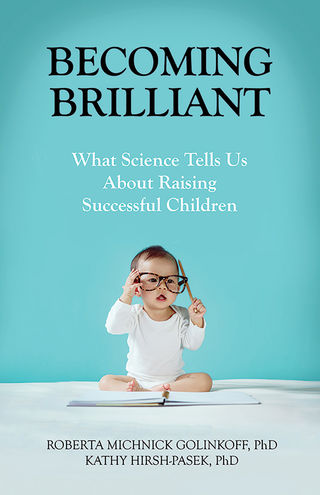

Becoming Brilliant

The Book Brigade talks to psychologists Roberta Golinkoff and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek.

Posted August 18, 2016

Every adult is anxious about the future in our fast-changing world. Parents especially are going to great lengths to push their kids to achieve, in the hope that will guarantee success. But they’re going about it exactly the wrong way. The science of learning is clear about how kids learn—and how we adults can help them get all the smarts they’ll need.

Your book is titled Becoming Brilliant. Is that meant to be ironic? Isn’t our culture suffering from parental efforts to raise brilliant kids?

Yes, it is kind of ironic, but in a way what we are trying to do here is to redefine what it means to be successful and brilliant. We want to move the needle and ask parents and policy makers to understand that a person is not and will not be brilliant by merely memorizing knowledge and spitting it out on a test. As a society we are obsessed with this kind of “brilliance” and this is totally misguided. We recently saw a product that is a kind of tampon device that pregnant women could insert to deliver information to their fetus. The marketplace is trying to convince parents to teach while the fetus is still in the womb. We have seen special toilet training seats that allow children to learn with tablets while they learn to control their bodies. There is a device parents can buy to count the words babies hear and another that detects how much they roll in their cribs before they sleep. We watch it all from a 24/7 monitor.

These products are neither needed nor appropriate for our children. But they tell us something about our society—a society that has lost its way and that considers success and “brilliance” the outcome of some score in a prescribed outcome area.

Our book takes a different stance—one offered through the lens of the science of learning. We suggest that real success and brilliance come when we support “happy, healthy, thinking, caring, and social children so that they become collaborative, creative, competent, and responsible citizens tomorrow.”

This mission statement for our book is adapted from our northern neighbors in Canada, who did a massive reorganization of their educational system and drove it to number 5 on the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment, administered by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) scores. We hover at around 29th to 32nd place in math and reading.

How do you achieve that kind of success?

We create a society that supports the learning of a breadth of skills in and out of school and that moves beyond a laser focus on content to include skills like collaboration (social skills, building community, learning to control social impulses); communication (listening, strong language skills; writing); content (the 3Rs and so much more, with learning to learn and executive-function skills); critical thinking (learning how to sift through information and to retain what is relevant to the problem at hand); creative innovation (putting information you have together in new ways, divergent thinking); and confidence (grit, positive mindset).

These 6Cs are grounded in research in the science of learning and are malleable. They help us to better define “brilliance” in a way that is consistent with how we learn from the sandbox to the boardroom and they are consistent with what business leaders claim are the leading skills needed for success in a global workforce. That’s why our book is for more than just parents; we all need the 6C’s in this ever-changing world.

There’s a big debate in our culture about intelligence and its plasticity (not to mention, even, exactly what the heck intelligence is). Is it possible to really boost kids’ intelligence?

As you rightly mention, intelligence is not a singular entity and much debate has ensued in the field about the operational definition of intelligence. Thus, the answer to your question depends on your definition. Can we help kids get smarter—to be better critical thinkers, to be more creative? Yes, undoubtedly we can, and we have some very good science to demonstrate the strategies that will elevate children’s learning outcomes and their learning to learn skills.

As just one example, learning to read depends not merely on learning the alphabet and letter-to-sound correspondence, as critical as this is. Learning to read demands that you have a strong language base so that when you do sound out those words, you find meanings that make sense to you. After all, the whole purpose of reading is extracting meaning from the printed page! And learning language rests on having the social and engaging conversations that build a foundation upon which communication grows. We sure can improve children’s language—and other aspects of what has been considered “intelligence.” So, you see, “intelligence” (as Howard Gardner and others noted years ago) is not merely the outcome on a test score, but is a number of intelligences that together allow children to learn and to navigate their environment.

And just what do you consider the critical elements of intelligence?

As you can tell, we have stayed away from intelligence as the driving term. There is no need to rehash old controversies or to stoke new ones. Instead, we ask what are the critical elements of learning. We also focus on the elements of learning that are grounded in science and are malleable. Our best guess—as we culled from the thousands and thousands of research papers we used in the book—was the 6Cs on the grid below. We not only spend time discussing the rationale for these particular six in our book, but importantly, we demonstrate how these skills are interconnected to form a dynamic learning model.

Using our rich science as a backdrop, we created the grid to demonstrate how the 6Cs build on each another over time and how there is also growth within each of the skill areas. Our story is one of a breadth of skills that becomes a dynamic learning model; like a spiral, it continues to build on itself over time. If we can change the lens on the way we think about learning and can embrace the science, we believe that we can create environments, in school and out, that will better support children’s “brilliance” and success.

How do children learn—and why don’t we all know this already?

We know quite a bit about how children learn. Unfortunately, we do not use what we already know. We often look for answers that are expedient, easily adaptable, quickly measurable with existing instruments. We need to step back to re-evaluate what we are hoping for our children’s future. We need to ask how we might truly prepare our children for a changing world and for the workplace of tomorrow.

We saw a wonderful analogy recently that puts this in perspective. The author—pointing out that times have changed yet we have not adapted to a Wiki learning model where facts are literally now at our fingertips—observed that we keep rearranging the furniture to see if we can make it fit better when what we really have to do is to redesign the house. So it is with education. We are teaching for a time when we were an agrarian society and things needed to be memorized. We wrote the book to help parents see that there is something they can do. Changing the schools is like turning a giant ocean liner—it’s very slow. Parents and others who interact with kids can—very naturally and in a playful way—infuse children’s lives with opportunities to advance along the 6Cs! The research on children’s learning requires that we cast away the old tests and old thinking about what we mean by “smarts.”

How do schools, the very institutions we count on for this job, get children’s learning wrong?

They use a laser focus on content and outcomes of test scores. That is not what real learning is about. Real learning embraces the 6Cs and we must create environments that foster real learning, not just a piece of it. Although there are many wonderful schools and teachers trying to encourage the breadth of skills that children need, high-stakes tests really limit what they can do.

We are trying to ensure that our children will be adaptable and flexible; the 6Cs do that. Our children will likely have jobs that have not yet been invented and will have to go beyond what a computer or robot can do. A recent story on NPR described a 2013 study from England that estimated that 47 percent of all jobs are in danger of automation! In just the next four years, according to the World Economic Forum, five million jobs will likely vanish.

If there was one change you could make in the way kids are raised or taught, what would it be?

Kids need to be kids. They need to play and get dirty, experience joy and have time to build relationships. We are so busy trying to make them smarter that we have forgotten that real “brilliance” emerges when children tinker with toys, build forts, and play with other children. A lot of research from Alison Gopnik’s laboratory suggests that children are like little scientists, and play is the testbed for their hypotheses. We need to do more to respect children’s intelligence and to give them the time to engage in playful learning, both in and out of school! We need to talk at kids less and have conversations with them, and we need to encourage them to question and come up with their own solutions to problems they face. Overmanaging kids—as Psychology Today’s Hara Estroff Marano has called it, “invasive parenting”—does not afford children the freedom they need to grow into independent, resilient, and confident humans who care about others and can manage their lives.

The future is unknown; how do we nevertheless educate kids who are prepared to thrive in it?

The 6Cs prepare children with the skills they need to explore and succeed at the frontiers of knowledge. We live in the knowledge age where information is doubling every 2.5 years. That means that if we teach our children every fact that is known today, in just two and a half years their knowledge base will be down to 50 percent and to 25 percent in five years. We need to help them learn how to learn, to critically think, to work with others, to creatively solve less-defined problems. These are the children who will readily adapt and embrace change and succeed even in this new age.

Curiosity seems so important; curious kids seek answers and essentially educate themselves—and keep on doing it. How do we turn on more curiosity?

Curiosity flourishes when children are encouraged to explore and discover. It is muzzled in an environment where we ask children to spit back memorized answers. Curiosity flourishes when children are the agents of their own learning, when they are active, not passive, learners. It is squelched when they must constantly color within the lines. Curiosity abounds when children tinker—when they can learn from their mistakes. It drowns when they are told there is but one right answer for any problem and that failure is not an option.

Not every parent has the luxury of choosing a fabulous school for their kid(s). What can parents do to foster their kids’ smarts that doesn’t make everyone anxious in the process?

No wonder parents are anxious. They are barraged with information about how to start the learning early, how they can spend just $300 to count every word that their children hear. The great irony is that they do not need to spend anything. Ours is not a solution that requires wealth. Parents just need to change the lens on how they view learning and to recognize the learning opportunities in the everyday moments. What makes trees bend in the wind? What is a star and why does it shine? Can we make shadows that look like dogs or roosters? What makes a shadow get bigger or smaller? Can I find math in the supermarket? Literacy in the doctor’s office? And how can I transform that toilet paper roll into a megaphone?

The world is bursting with opportunities to build collaboration, communication, content, critical thinking, creative innovation and confidence. We just have to learn to see them, and once we do, we will find teachable moments in every corner of our experience.

About THE AUTHOR SPEAKS: Selected authors, in their own words, reveal the story behind the story. Authors are featured thanks to promotional placement by their publishing houses.

To purchase this book, visit