Dopamine

How Dopamine Signals in the “Little Brain” Boost Sociability

Researchers found interesting results about dopamine workings in the cerebellum.

Posted June 17, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- In 1998, Harvard Medical School's Jeremy Schmahmann published a paper that upended how we view the cerebellum's role in social cognition.

- Before "Cerebellar Cognitive Affective Syndrome" was named in 1998, most brain experts didn't think the cerebellum affected social behavior.

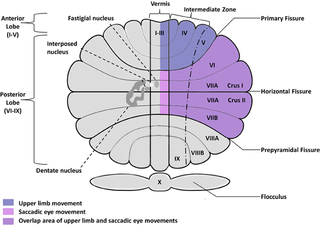

- New research on the cerebellum's role in sociability suggests that the strength of dopamine signaling in Crus I/II may regulate social behaviors.

Prior to the publication of a game-changing Brain paper by Jeremy Schmahmann and Janet Sherman of Harvard's Massachusetts General Hospital in 1998, most neuroscientists viewed the cerebellum as a motor-function-only brain region that coordinated muscle movements but had nothing to do with cognition or social behaviors.

For example, as a rookie tennis player in the 1970s, my neuroscientist father, who also worked at Harvard Medical School, coached me on weekends and incorporated cerebellar functions into my tennis lessons. Dad taught me how the cerebellum's Purkinje cells held muscle memory and helped athletes excel at sports by making it possible to hit home runs, kick field goals, and serve aces without consciously thinking about every move.

As a tennis coach, Dad knew that achieving peak performance on the court was more likely if a player trained the so-called "little brain" to perform fine-tuned muscle movements with automaticity. He also knew that optimizing cerebellar functions facilitated superfluidity (a frictionless flow state) and made it less likely that a tennis player would choke due to overthinking every stroke.

Additionally, because my father was both a neuroscientist and a neurosurgeon, his metacognitive knowledge about the role that Purkinje cells played in muscle memory and not choking gave him grace under pressure when operating on other people's brains. Much like "practice, practice, practice" improved his cerebellum's ability to serve aces and avoid unforced errors on the tennis court, Dad also credited optimizing cerebellar functions with making him a better brain surgeon in the operating room.

As a 20th-century brain surgeon, my father operated on people who had cerebellar lesions, tumors, or damage to different parts of the cerebellum. Throughout the 1970s, '80s, and '90s, he noticed that, in some patients, cerebellar abnormalities didn't seem to affect motor functions but did affect them in other ways. Because nobody thought the cerebellum was involved in non-motor functions at the time, these observations were confounding.

The Cerebellum's Role in Social Cognition Remains a Mystery

When Dad served as a medical consultant for my book The Athlete's Way in 2005, he encouraged me to put the cerebellum and Purkinje cells in the spotlight because of their well-established role in motor processes and athletic mastery of complex motor sequences.

Also, based on his first-hand observation of cerebellar abnormalities affecting social and emotional processes and accumulating evidence-based research, he also advised that any brain maps of cerebro-cerebellar circuitry included in the book should represent that the cerebellum wasn't just a motor-function-only brain center.

That said, in the aughts, nobody really knew that different regions of the cerebellum and cerebellar microzones were involved in motor and non-motor functions. Dad's way of summing up all of the cerebellar unknowns circa 2005 was to say, "We don't know exactly what the cerebellum is doing, but whatever it's doing, it's doing a lot of it."

It wasn't until about 2015 that neuroscientists began to zero in on how different regions and microzones of the cerebellum play a role in social cognition.

"Research on the relationship between the cerebellum and social cognition is very young, and apart from occasional early contributions, began to emerge over the past five years," Frank Van Overwalle and Mario Manto wrote in 2020. "Prior reports on the social role of the cerebellum were often limited to side aspects of affective processing and anecdotally described cerebellar patients having affective deficits."

Dopamine D2 Receptors in the Cerebellum May Regulate Social Behavior

Over the past decade, neuroscientists have been trying to pinpoint how the cerebellum influences social behavior in humans and animals.

A new animal study (Cutando et al., 2022) by an international team of researchers sheds light on how dopamine D2 receptors (D2Rs) regulate social behavior in mice. These findings were published on June 16 in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Neuroscience.

"We have uncovered an unexpected causal link between Purkinje cells' [dopamine] D2R expression levels right in the center of the cerebellum, the Crus I/II lobules, and the modulation of social behaviors," first author Laura Cutando of Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) said in a June 2022 news release.

"Reducing the expression of this specific dopamine receptor impaired the sociability of mice as well as their preference for social novelty, while their coordination and motor functions remained unaffected," she wrote.

Cutando et al. used genetic tools and different mouse models to investigate how altering D2R levels in cerebellar Purkinje cells could modify social behaviors without affecting motor functions. By selectively modifying dopamine D2 signaling in a mouse's Purkinje cells, the researchers could analyze how under- and over-expression of D2Rs affected motor and non-motor cerebellar functions. As mentioned, reducing dopamine D2R levels of expression made mice less social, whereas increasing D2R signaling increased sociability.

According to the researchers, these findings may pave the way for advancing our understanding of how dopamine signaling in the cerebellum plays a role in psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Of course, human studies are needed to identify how cerebellar dopamine D2 receptors regulate social behaviors in people.

References

Laura Cutando, Emma Puighermanal, Laia Castell, Pauline Tarot, Morgane Belle, Federica Bertaso, Margarita Arango-Lievano, Fabrice Ango, Marcelo Rubinstein, Albert Quintana, Alain Chédotal, Manuel Mameli, Emmanuel Valjent. "Cerebellar Dopamine D2 Receptors Regulate Social Behaviors." Nature Neuroscience (First published: June 16, 2022) DOI: 10.1038/s41593-022-01092-8

Frank Van Overwalle, Mario Manto, Zaira Cattaneo, Silvia Clausi, Chiara Ferrari, John D. E. Gabrieli, Xavier Guell, Elien Heleven, Michela Lupo, Qianying Ma, Marco Michelutti, Giusy Olivito, Min Pu, Laura C. Rice, Jeremy D. Schmahmann, Libera Siciliano, Arseny A. Sokolov, Catherine J. Stoodley, Kim van Dun, Larry Vandervert & Maria Leggio. "Consensus Paper: Cerebellum and Social Cognition." The Cerebellum (First published: July 07, 2020) DOI: 10.1007/s12311-020-01155-1

Jeremy D. Schmahmann and Janet C. Sherman. "The Cerebellar Cognitive Affective Syndrome" Brain (First published: April 01, 1998) DOI: 10.1093/brain/121.4.561