Depression

Serotonin Plays a Surprising Role in Fight-Flight-or-Freeze

Serotonin prompts the brain to take flight or freeze depending on threat levels.

Posted February 1, 2019 Reviewed by Davia Sills

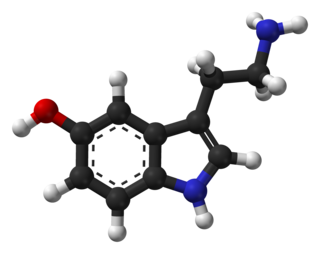

An eye-opening, new serotonin-based study (Seo et al., 2019) on mice was published today in the Feb. 1 issue of Science. These findings shed light on surprising ways serotonin may help the brain instantaneously execute fight-flight-or-freeze behavior during emergencies.

The paper, “Intense Threat Switches Dorsal Raphe Serotonin Neurons to a Paradoxical Operational Mode,” was co-authored by a team of researchers in the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior at Cornell University, led by senior author Melissa Warden.

Warden and her team were surprised to find that serotonin neurons in mice (and most likely humans) have an uncanny, chameleon-like ability to flip behavior depending on the degree of a potential threat.

For example, in high-threat situations, stimulating serotonin neurons in the prefrontal-dorsal raphe nucleus (which is a serotonergic hub) triggers escape attempts as a mouse tries to take flight. On the flip side, in less urgent and lower-threat situations, stimulating these exact same dorsal raphe serotonin neurons causes the mouse to freeze in place.

As the authors explain, “Our findings show that urgent escape conditions switch DRN 5-HT [serotonin] neurons from suppression of movement to facilitation and that DRN GABA neurons selectively facilitate movement in environments with negative valence, consistent with the neural dynamics that we observed in both cell types. These results reveal a role for prefrontal-dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) circuits in rapid, environment-specific behavioral regulation.”

The main takeaway of this research is that during "intense threat," emergency fight-flight-or-freeze situations, the serotonin-driven behavioral choices a mouse in a lab makes are different from the decisions the same mouse would make under less-perilous circumstances.

"Considering the widespread distribution of serotonin neurons throughout the brain, this finding raises the possibility that the 'emergency brain' operates in a fundamentally different way," Warden said in a statement.

I'm on a lifelong mission to destigmatize the open discussion of personal mental health issues. Therefore, the following section of this post shares some autobiographical examples of fight-flight-or-freeze responses and debilitating depressive symptoms filtered through the lens of recent, state-of-the-art research on serotonin, physical activity, and depression.

Discussion of Fight-Flight-or-Freeze Responses Based on a Combination of Life Experience and Empirical Evidence

Yesterday afternoon, I wrote a post, "Exercise May Promote Gene Expression of Feel-Good Chemicals," based on new research from McMaster University (Allison et al., 2019), which found that the combination of vigorous aerobic exercise and weight-lifting caused a chain reaction along the kynurenine pathway that resulted in the synthesis of more serotonin and a decreased depression risk.

Immediately after reading the latest study on fight-flight-or-freeze responses and serotonin by Seo et al. (2019) this morning, I had an Aha! moment about why discovering vigorous exercise training—during a period of intense threat in my adolescent life as a gay teen—was a lifesaver. Hopefully, sharing this first-person narrative will inspire readers from all walks of life who are prone to crippling anxiety or debilitating depression to "freeze" less and move more.

During the winter of 1983, when I was 16 going on 17, I experienced a tsunami of unexpected, adverse experiences that created an emergency, “intense threat” situation. Being blindsided by these threats to my existence required "rapid, environment-specific behavioral regulation."

Unfortunately, at the time, I was at a boarding school, where we regularly anesthetized our teenage angst with drugs and alcohol. All I wanted was to be “comfortably numb.” In this self-medicated state of complacency, I didn’t realize at first that substance abuse was like pouring gasoline on my predisposition for debilitating depression.

Eventually, the symptoms of this major depressive episode (MDE) got so bad that I couldn’t get out of bed. At my lowest point, just after the end of the spring semester, I spent every day at home curled up in a fetal “freeze” position and "hid 'neath the covers and studied my pain" from sunrise to sundown.

If I take a moment to imagine myself as a mouse in the above-mentioned serotonin experiment from Warden’s Lab at Cornell University... I'd make an educated guess that during this phase of my life, my serotonin neurons responsible for facilitating movement to take "flight" and escape a threat were locked in the “freeze” response mode. As someone who lived through this, I know firsthand that not getting any daily exercise for weeks on end seemed to exacerbate the severity of my depressive symptoms

Thanks to the sheer luck of being in the right place at the right time, on a sunny June afternoon in 1983, I dragged myself out of bed and went to see a matinee of Flashdance at the Cleveland Circle Cinema near where I lived at the time, just outside of Boston. The Giorgio Moroder theme song from this movie combined with Donald Peterman’s brilliant, bursting-with-light cinematography sparked something inside that made me want to put on my Walkman and join all the joggers running around the Chestnut Hill reservoir.

This moment in time was a pivotal turning point in my life. After a few days of lacing up my sneakers and going for a jog, the deep-freeze of my “frozen” state of body and mind began to thaw, and my depressive symptoms subsided. Anecdotally, I have a hunch that “taking flight” as a runner "flipped on" some serotonin-related switches in my brain that boosted my mood. That June, I also joined a gym and began lifting weights religiously.

Full disclosure: My inspiration to start jogging and “pumping iron” in the early 1980s was also fueled by negative emotions and low self-esteem associated with internalized homophobia and what some might call “sissy-boy syndrome.” A big part of my motivation to get in shape when I was 17 years old was that I wanted a more masculine physique.

My role model was Brazilian-born pole vaulter Tom Hintaus, who unwittingly ushered in the beginning of Madison Avenue “sexually objectifying men” in the iconic Calvin Klein underwear ads photographed by Bruce Weber. The slick, homoerotic Spring/Summer GQ images by Rico Puhlmann that graced the glossy pages of GQ Magazine served as the motivational rocket fuel that inspired me to push myself harder at the gym.

Whenever I worked out, I’d blast mixtapes of Hot 100 music from the summer of 1983 that often included the tongue-in-cheek anthem “I Can Make You a Man” from Rocky Horror Picture Show. The combination of these feel-good Top-40 pop songs and sexually-charged visual imagery inspired me to exercise vigorously and get stronger. Maybe these images boosted my libido and testosterone levels, too?

The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss has a "my story" chapter in which I describe the metamorphoses of my mind, body, and brain that summer:

“When I started running in June 1983, my body was a toxic waste dump. I could run for about 12 minutes maximum. I was a weak, washed-out, drug-abusing teenager. From June to September, I went from being a cynical and hopeless adolescent kid to being an enthusiastic, ambitious go-getter. More impressive to me than having a new semi-washboard stomach and relatively strong, seventeen-year-old biceps was that my brain had been transformed. I felt unstoppable. I walked with a new kind of peppy step and moved with intent. Running turned my life around. My confidence and self-esteem grew in tandem with my weekly mileage. At first, I could only make it once around the reservoir, but by August, I could run for more than an hour and do the whole outer loop. My learned helplessness and self-loathing dissolved; I had developed a sense of agency. I went from being a straight C- student in high school to blazing through Hampshire College in three years on campus. When you feel the connection between sweat and the biology of bliss in your brain for the first time, it’s like being born again. Exercise gives you the courage and tenacity to take life by the horns and say, ‘Yes—I can!'"

One reason I relive the events and key ingredients from the summer of 1983 time and time again is an attempt to make myself a human "lab rat, guinea pig, or mouse" in a real-world neurobiology and behavior laboratory. My goal is to identify key factors that might have the universal power to help others who are prone to clinical depression to improve their mental health.

For the record: Exercise is not a panacea for depression. A few days ago, in response to my post, "More Evidence That Physical Activity Keeps Depression at Bay," a PT reader "Marko" commented, "Exercise may help with depression, but let's emphasize that it or any other treatment is no silver bullet, and it won't cure the condition. Exercise is part of the treatment process." I agree with Marko. As someone who is prone to major depressive disorder (MDD), I view all of the daily "interventions" and things I do proactively from day-to-day to keep my depression at bay as a "treatment process" I will need to monitor and adapt across my lifespan continually.

Another reader, "Donna," commented, "Don't make a person prone to depression feel bad about how they are managing their depression. It's hard enough already." I agree with Donna, too. My intention here is not to make anyone feel bad about her level of physical activity.

That said, through the lens of the latest serotonin research, I have a hunch that finding ways to flip the paradoxical operational mode of dorsal raphe serotonin neurons into a “Go!” position might help those of us who are prone to clinical depression be less likely to get stuck in "freeze" mode.

Hopefully, learning about the latest evidence-based findings from Seo et al. (2019) and Allison et al. (2019) will inspire anyone reading this who is currently experiencing depressive symptoms to kickstart an exercise regimen as a possible way to flip your "paradoxical serotonin switch" in the dorsal raphe out of the "freeze" mode and produce more feel-good serotonin via the kynurenine pathway.

References

Changwoo Seo, Akash Guru, Michelle Jin, Brendan Ito, Brianna J. Sleezer, Yi-Yun Ho, Elias Wang, Christina Boada, Nicholas A. Krupa, Durgaprasad S. Kullakanda, Cynthia X. Shen, Melissa R. Warden. "Intense Threat Switches Dorsal Raphe Serotonin Neurons to a Paradoxical Operational Mode." Science (First published: February 1, 2019) DOI: 10.1126/science.aau8722

David J. Allison, Joshua P. Nederveen, Tim Snijders, Kirsten E. Bell, Dinesh Kumbhare, Stuart M. Phillips, Gianni Parise, Jennifer Heisz. "Exercise Training Impacts Skeletal Muscle Gene Expression Related to the Kynurenine Pathway" American Journal of Physiology–Cell Physiology (First published online: January 16, 2019) DOI: 10.1152/ajpcell.00448.2018