Depression

Vagus Nerve Stimulation Offers New Hope for Major Depression

VNS improves quality of life for patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Posted August 22, 2018

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) significantly improves quality of life for patients with treatment-resistant depression—even when their depressive symptoms do not wholly subside—according to a new study of 599 patients with major depression that wasn’t alleviated by so-called “treatment as usual.” Typical treatment for clinical depression generally includes a combination of antidepressant drugs, psychotherapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, or electroconvulsive therapy. This paper, “Chronic Vagus Nerve Stimulation Significantly Improves Quality of Life in Treatment-Resistant Major Depression,” was published online August 21 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

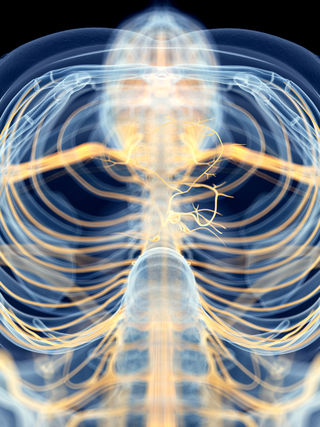

Vagus nerve stimulators are surgically implanted in the chest or neck near the collarbone during an outpatient procedure that generally takes about an hour. The small, pacemaker-like device sends a prescribed dosage of electrical current to the brain via the vagus nerve at regular intervals.

It’s estimated that two-out-of-three patients suffering from major depressive disorder (MDD) do not benefit significantly from the first prescribed antidepressant he or she tries. Ultimately, about one-third of clinically depressed patients are treatment-resistant to antidepressant pharmaceuticals such as SSRIs, SNRIs, or MAOIs.

In 2005, the Food and Drug Administration approved the clinical use of vagus nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. In 2017, a study found that VNS significantly improved treatment-resistant depression outcomes over a 5-year period. These findings were published in the American Journal of Psychiatry. (For more see, “Vagus Nerve Stimulation Helps Treatment-Resistant Depression.” )

For the most recent study on vagus nerve stimulation, the researchers wanted to move beyond simply evaluating patients’ treatment-as-usual response to antidepressants. In a statement, principal investigator Charles Conway of Washington University said, “When evaluating patients with treatment-resistant depression, we need to focus more on their overall well-being. A lot of patients are on as many as three, four or five antidepressant medications, and they are just barely getting by. But when you add a vagus nerve stimulator, it really can make a big difference in people's everyday lives."

For this study, researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine compared 328 treatment-resistant depressed patients with implanted VNS devices (many of whom also took antidepressants) with 271 TRD patients who only received “treatment as usual” that did not include stimulating the vagus nerve.

To assess quality of life, the researchers evaluated 14 categories, which included overall well-being, general physical health, social relationships, family dynamics, ability to work, etc.

"On about 10 of the 14 measures, those with vagus nerve stimulators did better," Conway said in a statement. "For a person to be considered to have responded to a depression therapy, he or she needs to experience a 50 percent decline in his or her standard depression score. But we noticed, anecdotally, that some patients with stimulators reported they were feeling much better even though their scores were only dropping 34 to 40 percent."

In a press release from Washington University School of Medicine, one of the study participants, Charles Donovan—who had been hospitalized several times for depression and did not respond to treatment-as-usual prescriptives before having a VNS device implanted—shares his personal story:

"Before the stimulator, I never wanted to leave my home. It was stressful to go to the grocery store. I couldn't concentrate to sit and watch a movie with friends. But after I got the stimulator, my concentration gradually returned. I could do things like read a book, read the newspaper, watch a show on television. Those things improved my quality of life,” Donovan said. "Slowly but surely, my mood brightened. I went from being basically catatonic to feeling little or no depression. I've had my stimulator for 17 years now, and I still get sad when bad things happen—like deaths, recessions, job loss—so it doesn't make you bulletproof from life's normal ups and downs, but for me, vagus nerve stimulation has been a game-changer.”

Charles Conway speculates that one of the keys to improved quality of life associated with VNS may be that vagus nerve stimulation appears to improve someone’s ability to concentrate. "[VNS] improves alertness, and that can reduce anxiety. When a person feels more alert and more energetic and has a better capacity to carry out a daily routine, anxiety and depression levels decline,” Conway concluded.

References

Charles R. Conway, Arun Kumar, Willa Xiong, Mark Bunker, Scott T. Aaronson, and A. John Rush. "Chronic Vagus Nerve Stimulation Significantly Improves Quality of Life in Treatment-Resistant Major Depression.” The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry (First published online: August 21, 2018) DOI: 10.4088/JCP.18m12178

Scott T. Aaronson, Peter Sears, Francis Ruvuna, Mark Bunker, Charles R. Conway, Darin D. Dougherty, Frederick W. Reimherr, Thomas L. Schwartz, and John M. Zajecka. "A 5-Year Observational Study of Patients With Treatment-Resistant Depression Treated With Vagus Nerve Stimulation or Treatment as Usual: Comparison of Response, Remission, and Suicidality." American Journal of Psychiatry (First published: July 01, 2017) DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16010034